Media policy

Confusion over misleading claims that Google Maps changed its Russian satellite imagery policy

Russian censors hesitate to ban YouTube

New Russian commission latest indicator country might eventually disconnect from global internet

Tracking narratives

Troll campaign targeted Polish public figures to distract from Bucha massacre coverage

Confusion over misleading claims that Google Maps changed its Russian satellite imagery policy

On April 18, thousands of posts appeared across Twitter claiming that Google Maps had supposedly unblurred satellite images of Russian military installations. These reports caused a wave of excitement among curious internet users, as searches for “google maps Russian military bases” increased significantly.

Google Maps quickly released a statement denying that it had made any recent changes to its satellite imagery of Russia. According to the statement, unblurred versions of the imagery were already available on Google Maps, while independent researchers noted they had been able to access these kinds of images for years.

Although the original source of the Google Maps rumor is still unclear, the earliest mention identified so far is by defence-ua.com on April 17, the day before it spread heavily across Twitter. The article, “Find Putin’s Bunker: Google has opened high-quality satellite images of all strategic points in Russia,” included multiple satellite images of Russian bases and equipment. For example, one photo showed recent imagery of the Russian naval carrier Admiral Kuznetsov in Murmansk, Russia. Using Google Earth, however, the DFRLab found high-resolution Google imagery of the ship dating back to 2019 that was also unblurred.

Some coverage pointed to an April 18 tweet by @ArmedForcesUkr as the source, but text and images from this tweet matched the defence-ua.com article from the previous day, suggesting the Twitter account relied on the article as its source. Twitter suspended @ArmedForcesUkr sometime on April 19, although the reason is currently unknown. While previously cited by Ukrainian government officials, it was not a verified government account.

At the time publishing, it is unknown whether the original article was a misunderstanding or intentional disinformation. The incident has already been used by Russian outlets to bolster their claims that Ukrainian information sources cannot be trusted.

—Ingrid Dickinson, Young Global Professional, Washington DC

Russian censors hesitate to ban YouTube

The Russian government’s unwillingness to ban access to YouTube—after two months of escalating threats and intimidation—is revealing the practical limits of the Kremlin’s censorship regime. It also demonstrates the inadequacy of video-hosting alternatives offered by Russia’s domestic technology sector.

YouTube had approximately 91 million Russian users in 2021, making it the most popular public-facing internet platform in the country. For more than a decade, YouTube has essentially monopolized video hosting in the country. Rutube—Gazprom’s competing video service that was launched contemporaneously with YouTube in the mid-2000s—had just 3 million users in 2021. VK Video, made available to VKontakte users in late 2021 and marketed as a YouTube competitor, does not appear to have significantly threatened YouTube’s market share.

The scale and durability of YouTube’s popularity appears to have given pause to Russian censors. In recent weeks, Roskomnadzor has accused Youtube (and its owner Google) of being a “tool of anti-Russian information warfare,” issued numerous demands for the reinstatement of government YouTube channels, banned the advertising of Google products, and even ordered Yandex and other domestic Russian search engines to append a warning label to YouTube links. Russian courts have threatened YouTube with fines, while Russian legislators have proposed an official ban. Yet in practice, nearly a month after Russia officially blocked Facebook and Instagram, YouTube remains as accessible as it was before the war began.

At the same time, the Russian government has undertaken a largely anemic public relations campaign to push Russian users toward domestic video alternatives. According to reporting by Kevin Rothkrock, VKontakte has begun advertising a tool to automate video migration from YouTube to VK Video, while Rutube has reformed its cumbersome content moderation requirements that previously required manual review of every uploaded video, as creators can now bypass this requirement by uploading a copy of their passports. At least one Russian YouTuber claims that bots have begun spamming his YouTube comments section with links to Rutube.

Although the user base of Russian video services appears to be growing – the Rutube app saw 1.1 million new downloads in March 2022 – these Russian alternatives remain dwarfed by YouTube. Should the Russian government institute a formal YouTube ban, it will mark an unprecedented and deeply unpopular disruption of the Russian internet.

—Emerson T. Brooking, Resident Senior Fellow, Washington DC

New Russian commission latest indicator country might eventually disconnect from global internet

Last week, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree to create an interagency commission of the Security Council of the Russian Federation that will work on issues related to the country’s technological sovereignty and critical information infrastructure.

According to TASS, the commission will ensure the “technological independence of critical information infrastructure objects from foreign technologies in the field of creation and production of domestic products.” It will be led by Dmitry Medvedev, the former president and prime minister currently serving as deputy chairman of Russia’s security council. The Kremlin-owned outlet RIA, meanwhile, explained that critical information infrastructure includes “information systems of government agencies, enterprises of the military-industrial complex, healthcare organizations, transport, communications, credit and financial sector, energy, fuel, nuclear, rocket and space, mining, metallurgical and chemical industries.”

In February of 2021, Medvedev stated that Russia was “legislatively and technologically ready to disconnect from the global internet,” though later added that there were “no signs yet that this could happen.”

The newly created commission consists of up to thirty members, including Russia’s ministers of defense, foreign affairs, and emergency situations, as well as directors of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) and the Federal Security Service (FSB); general directors of space agency Roscosmos; state nuclear energy corporation Rosatom; and state corporation for developing and manufacturing advanced technology Rostec.

—Eto Buziashvili, Research Associate, Washington, DC

Troll campaign targeted Polish public figures to distract from Bucha massacre coverage

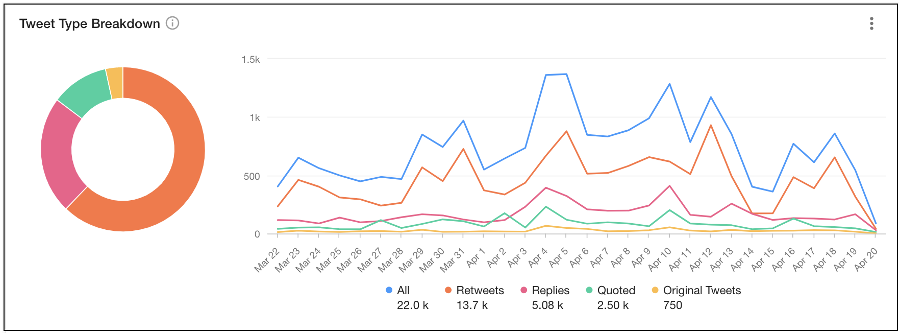

As the killing of Ukrainian civilians in Bucha dominated headlines in early April, a “large-scale troll attack” took place in Poland. According to EUvsDisinfo, the campaign was an attempt to divert public attention from the massacre. In an April 12 report on the incident, EUvsDisinfo described three main components of the attack. First, it sent threatening emails Polish public figures; this was followed by a second wave emails to Polish media alleging Ukraine had committed war crimes. Finally, the campaign attempted to make the 1943 Volyn massacre trend on Twitter.

EUvsDisinfo reported that an account sent emails containing death threats to hundreds of Polish public figures. Several politicians, including Radosław Sikorski, Dariusz Matecki, Maciej Lasek, and others, published screenshots revealing they all received identical messages. The emails were hostile and violent, threatening death with an air gun, ax, or immolation. The screenshots showed that an account named “Marcin Mikołajczak” sent the emails; it is unclear whether this name is a pseudonym.

Soon afterwards on April 5, Polish media figures were flooded with emails purported to be sent by ordinary Russians who wanted to report crimes committed by Ukraine. The messages, written in English and Polish, claimed that the Ukrainian army was committing war crimes. At least one of the emails contained a link to a graphic video published on Telegram claiming to show Russian soldiers who were tortured and killed by Ukrainian forces. A screenshot of the spam emails published by digital policy analyst and PhD candidate Katarzyna Chojecka revealed that repeated emails were received within intervals of only a few minutes.

The third component of the troll attack was an attempt to make the 1943 Volyn massacre trend on Twitter. EUvsDisinfo said that the topic trended on Polish Twitter on April 4 and 5, while the Polish fact-checking organization Konkret 24 reported via Getdaytrends.com that Volyn trended on April 10 and “rzeź wołyńska” (“Volyn massacre”) last trended in July 2019.

The DFRLab used social media analysis tool Meltwater Explore to analyze mentions of “Wołyń” (Volyn in English) and “rzeź wołyńska” (Volyn massacre). We found that these keywords were mentioned around 1,300 times on Twitter on April 4 and 1,166 times on April 5, more than doubling from April 3. Subsequent spikes took place on April 10 and 13.

—Givi Gigitashvili, Research Associate, Warsaw, Poland

Image: In this photo illustration the Google Maps logo seen displayed on a smartphone and in the background. (Photo by Rafael Henrique / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)No Use Germany.