A global trade war is not out of the question anymore. US President Donald J. Trump has set the first domino in motion, and it will be hard to stop.

A global trade war is not out of the question anymore. US President Donald J. Trump has set the first domino in motion, and it will be hard to stop.

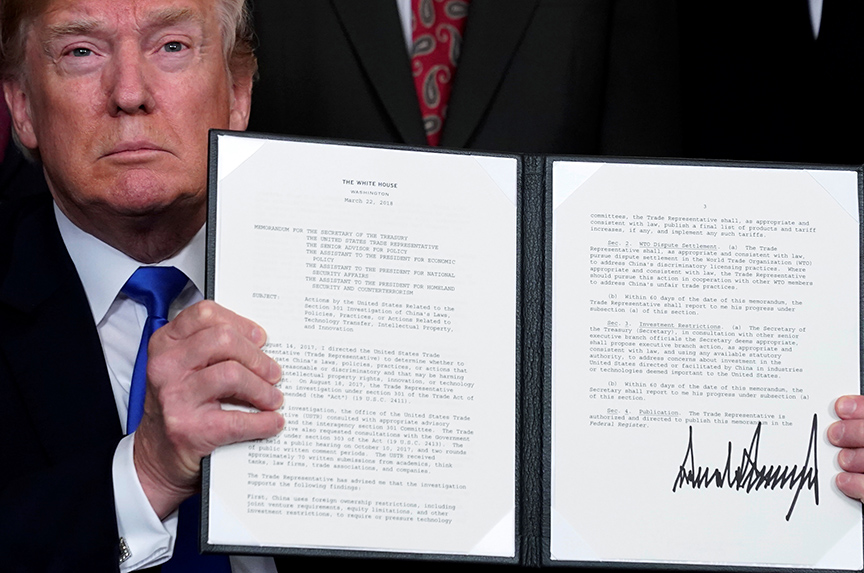

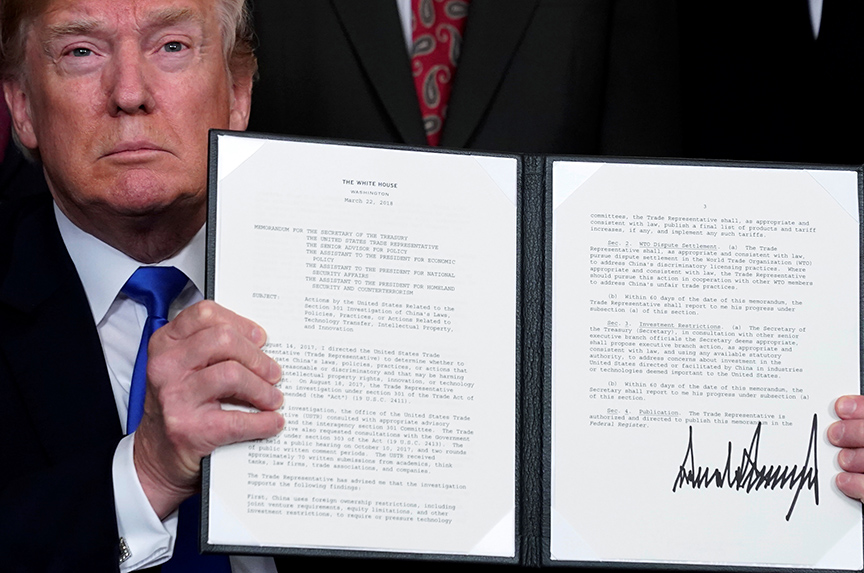

Specifically, Trump has in March alone imposed two tariffs—one targeting Chinese imports and the other the steel and aluminum imports. The latter go into effect on March 23.

Taken together, these tariffs will have far-reaching, global implications that could escalate into a trade war.

What is a trade war?

A trade war has two basic components.

First, it is often said to be a side-effect of protectionism—a situation in which one country retaliates against another that imposes trade barriers (e.g., tariffs and quotas) on the other country. In today’s highly interconnected global economy, these actions have implications for the warring countries’ trading partners as trade will be rerouted elsewhere. This creates the risk of other markets becoming flooded unless they take precautionary measures in the form of import quotas themselves, creating even more barriers to free trade.

Second, the reason for the action—when one country believes that another country’s trading practices are unfair. In this case, the United States is taking measures in response to China stealing and transferring intellectual property from US businesses, findings of the US Trade Representative’s so-called Section 301 investigation.

While the consensus in Washington seems to endorse a tougher stance on China overall, Trump’s actions are rash and it is hard to see the endgame. If anything, the timing could not be worse. The steel and aluminum tariffs that will come into force on March 23 do not necessarily create an environment in which many countries would be willing to support the currently unilateral actions of the Trump administration against China.

While some of the United States’ closest trading allies (Mexico, Canada, the European Union, Australia, Argentina, Brazil, and South Korea) are temporarily excluded from the tariffs on steel and aluminum coming into force on March 23, their relations with Washington have been strained and will remain tense. Rufus Yerxa, president of the National Foreign Trade Council, takes it a step further claiming that it “might create more sympathy than pressure for China.”

Who gets hurt in a trade war?

Short answer: Mostly not China.

Short-sighted short-term political gains are outweighed by long-term political and economic implications.

Politically: Trump’s actions are in line with his trade policy of “America First” and his campaign promises to be “tough on China.” Looking ahead to the mid-term elections in November, the tariffs on China might seem like a smart move for Trump to maintain the support of his voter base. However, if expert estimates are to be believed, his actions might not only offset his voters’ benefits from the tax cuts through higher prices for consumers, but Chinese retaliation might ultimately hit parts of his core the hardest.

In numbers: According to former US Trade Representative Michael Froman, “Everybody, all economies, will be adversely affected; the only question is how much.”

It is as yet unclear how China will retaliate, but it has several options. One would be export taxes on products to the United States but such a move might backfire on Chinese producers. Another more likely option would be tariff retaliation.

As one of the United States’ biggest buyers of crops (e.g., half of US soybean exports go to China), one likely option would be to target US agriculture—a vital part of US exports and Trump’s voter base.

Another option would be for China to move its business from Boeing to Airbus, which would massively hurt the United States’ biggest exporter.

Let’s not forget that with 19 percent of a total of $6.26 trillion in US debt to foreign creditors, China is the biggest holder of US debt. If China decided to “dump” large amounts of US debt as a retaliatory measure, it would become costlier for the US Treasury to issue new debt, which in turn would have detrimental implications for the affordability of debt stock. All that is to say that the starting lineup does not seem as favorable as Trump believes it to be.

Ultimately, trading partners of both the United States and China will be affected by what could likely be an escalation of retaliatory measures by the two countries. A global trade war, though still unlikely, is estimated to have a negative effect of 1-3 percentage points in the next few years to global GDP.

How did the last trade war end?

The (ab)use of economic safeguard clauses for political considerations is nothing new. In 2002, then US President George W. Bush imposed similar tariffs on certain steel imports, resulting in the loss of roughly 200,000 US jobs as a consequence of higher steel prices. This represented about $4 billion in lost wages and translated into more job losses than workers employed in the entire steel industry at the time.

During the twenty months of an import duty of 30 percent, steel producers from around the world filed a complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO). Critical US allies like the EU threatened to retaliate by targeting imports of important swing states with high tariffs. The Bush administration ultimately ended its tariffs because of the looming threat of European sanctions.

This time, a resolution of the situation might not be as easy: the Trump administration has heavily criticized multilateral organizations like the WTO, which undermines the likelihood of Trump accepting it as the problem solver. In addition, this time the opponent is a different one who might not be as benevolent and patient as the EU.

The first domino has been set in motion. In contrast to Trump’s claim that “trade wars are good and easy to win,” it is not clear what the goal of his “game” is and how many losers it will create along the way. The duration, scale, and outcome of the dispute will largely depend on whether the WTO will be able to facilitate a solution and if other players will be willing to stick to the rules of the global trading system.

Marie Kasperek is an associate director in the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program. Follow on Twitter @TRADE_in_ACTION.

Image: US President Donald J. Trump signed a memorandum on intellectual property tariffs on high-tech goods from China at the White House in Washington on March 22. (Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)