Atlantic Council analyst says track record of past ceasefires does not inspire confidence

A new deal between South Sudanese President Salva Kiir and rebel commander Riek Machar to end the fighting that has devastated the world’s newest nation over the past year is likely just a delaying tactic that allows the two warring sides to rearm and buys more time for the international community’s so far unsuccessful diplomatic efforts, says Atlantic Council analyst J. Peter Pham.

“I don’t think this deal is ‘the real deal,’” Pham, who is Director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center, said in an interview.

“It is an artifice to get away from Addis as quickly as possible and to buy time,” he added, referring to the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa where peace negotiations have been underway.

After signing the ceasefire agreement, Machar said some “critical issues” had not been resolved.

State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki said the partial accord was a “step towards a peace agreement,” but that “significant challenges remain.”

The US fully supports the Intergovernmental Authority on Development-led negotiations in Addis Ababa and Kiir and Machar must return to Addis Ababa “prepared to make the necessary compromises to form a transitional government,” said Psaki.

The two sides will meet again on February 20 to work out details of a power-sharing agreement and have until March 5 to reach a deal that paves the way for a transitional government.

African diplomatic sources have been reported as saying a final deal would keep Kiir in the role of President and re-instate Machar as his Vice President.

Such an arrangement would essentially return the balance of power in South Sudan’s capital Juba to what it was in July of 2013, before Kiir dismissed Machar from the role of Vice President. The political crisis triggered by that action escalated into a military one on December 15, 2013, as forces loyal to Kiir sought to crush what the government claimed was a coup attempt by Machar. US officials have repeatedly stated they have no evidence of any coup attempt.

Multiple ceasefire agreements between Kiir and Machar have fallen apart causing Pham to believe this latest deal will be no different.

The fault lies in part with the international community, which has not been able to stop the fighting or stem the flow of weapons into South Sudan, said Pham.

“It shows the limits of the international community’s influence because of its lack of political will to make credible threats,” he said.

US President Barack Obama on April 3, 2014, issued an executive order providing the authority to sanction individuals who threaten the peace, security, or stability of South Sudan. To date, only four relatively insignificant individuals have been designated under this authority.

“For want of spine and want of realism, the international community’s faith in talking while not backed up by credible force has been shown to be totally misplaced,” said Pham.

Pham spoke in an interview with New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Excerpts below:

Q: We have a deal in South Sudan where Salva Kiir will reportedly remain president, and Riek Machar as his vice president. This arrangement didn’t work in the past. Can it now?

Pham: One can always cling to hope, but there have been half a dozen ceasefires all honored in the breach, and three prior peace accords between Salva Kiir and Riek Machar all of which failed as well. So the track record does not give me a great deal of optimism that this deal is anything more than an attempt by both sides to sign something so they can leave Addis and at least avoid, for the moment, the threat of sanctions by the United Nations and the African Union.

Q: Doesn’t the threat of sanctions remain on the table if the deal falls apart?

Pham: It has just been threats. It buys the two sides time. Time means time to buy weapons and ship them in.

This is civil conflict that has gone on for more than a year, and yet the international community has not found the consensus to impose an arms embargo, which would at least help choke off the flow of additional weapons. Even if an arms embargo would be difficult to impose 100 percent, the fact that there hasn’t even been a consensus to impose one shows how weak and divide the international community is.

The United States, for example, talks about sanctioning those responsible for continuing the conflict. Yet the only people who have been designated for sanctions are a handful of commanders who no one has heard of outside the specialist community and likely don’t have any assets in the US to be frozen anyway.

Meanwhile, the leaders of the conflict on both sides maintain their families in Nairobi, Kenya, and other cities far from the fighting. These people are living luxuriously, unlike more South Sudanese. There is no freeze on their assets.

The international community has said more weapons are not helpful, yet Kenya has permitted Chinese weapons to be transshipped across its territory to Salva Kiir. Uganda’s military is involved in the fighting on Kiir’s side. The rebel side reportedly receives support from Sudan.

Q: Do we know the details of the deal?

Pham: They haven’t disclosed the details of the deal other than the fact that they have agreed to make peace and will reconvene in a few weeks to discuss the elements.

I don’t think this deal is “the real deal.” It is an artifice to get away from Addis as quickly as possible and to buy time.

It shows the limits of the international community’s influence because of its lack of political will to make credible threats.

Q: What should the international community be doing to ensure a deal sticks?

Pham: The international community should demonstrate some spine. This deal is buying time not just for the conflicting sides, but also for the failed diplomatic efforts of the international community.

For want of spine and want of realism, the international community’s faith in talking while not backed up by credible force has been shown to be totally misplaced.

Q: Why has the international community been unable to get a deal?

Pham: The international community can’t even agree on the set of facts that precipitated the crisis. Until you have diagnosed the disease you cannot prescribe a cure.

Q: What toll has the fighting between the forces of Kiir and Machar taken on South Sudan?

Pham: If the country was underdeveloped before it is now even behind that. Millions of people have been displaced. Crops were not planted during the fighting, which means there will be no harvest later this year. Significant — even catastrophic — food insecurity is imminent.

Ashish Kumar Sen is an editor with the Atlantic Council.

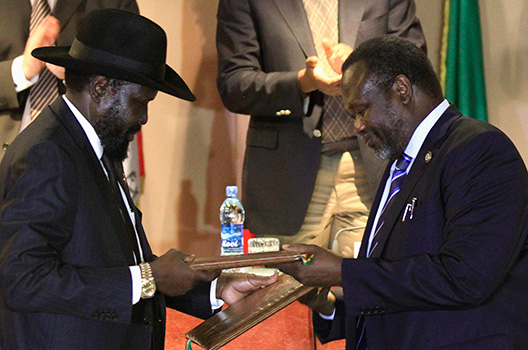

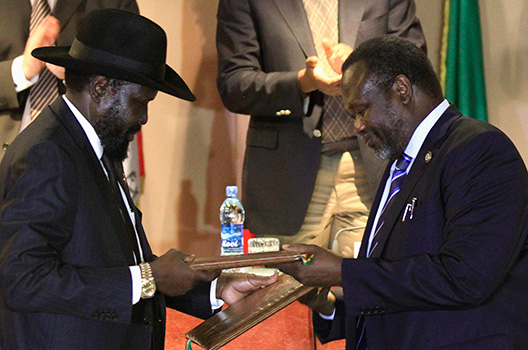

Image: South Sudan's President Salva Kiir (left) and rebel commander Riek Machar exchange documents after signing a ceasefire agreement in Ethiopia's capital Addis Ababa on Feburary 1. The partial accord edges the two sides closer to a final deal to end a 15-month conflict that has ravaged the world's newest country. (REUTERS/Tiksa Negeri)