Master Corporal Khamphone Phanthavong will never forget the day in Afghanistan when he learned firsthand what a difference his job as a radio operator can make.

It came at Forward Operating Base Masum Ghar in Afghanistan’s southern Kandahar province in 2007. Phanthavong was at the command post of Canada’s Third Battalion, Royal 22e Regiment when an Afghan interpreter working with the unit called with an alarming message.

“He told us that armed Taliban had kidnapped two brothers, and their mom wanted to know if we could help,” said Phanthavong, who came to Canada as a Laotian refugee in 1983.

Phanthavong quickly relayed the news to all units in the field. “By chance, we had a patrol very close to where the kidnapping happened, and they caught the Taliban with the boys,” he said.

“At the end of the day that mom had her kids back,” said Phanthavong, who called it one of the most satisfying days of his life.

The 39-year-old, who is now serving with NATO’s Canadian-led battlegroup in Latvia, knew he would be a soldier when he was just four years old. The eureka moment came in 1982, when his family was living in an Indochinese refugee camp near Posadas in northeastern Argentina.

He remembers watching wide-eyed as tanks, armored vehicles, and infantry rolled by, heading for the Falklands War with Britain.

“I thought to myself, ‘One day I’m going to be in one of those vehicles, and it’s going to be my work,’” he said.

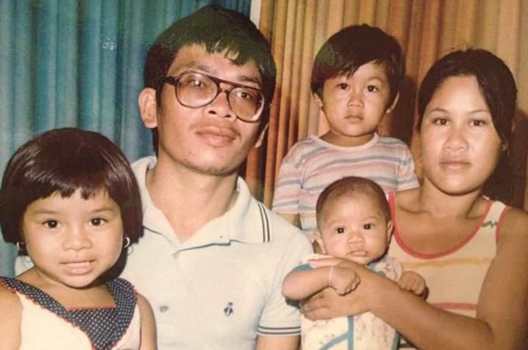

Phanthavong was born in a refugee camp in Thailand after his mother, father, and sister fled Laos in 1978. Thousands of Laotians were fleeing the country at the time after the Communist Pathet Lao seized power in 1975.

After being transferred from Thailand to the camp in Argentina, the family settled in the small Quebec city of St-Barnabé Nord in 1983 and later in Trois-Rivières, where Phanthavong finished high school.

Phanthavong became a dental technologist, making crowns and other mouth ware.

After three years of this exacting work, “I became tired of focusing on one centimeter under a microscope all day,” he said. “I needed something more—some action in my life.” So he joined the army.

He has been a communications expert—in military parlance a “signal soldier”—for his entire fifteen-year career. It has included two tours in Afghanistan—the one in 2007 at Masum Ghar and in 2010 with the 12e Régiment blindé du Canada at Sperwan Ghar, also in southern Kandahar province. Both times his units came under fire.

Communications is a critical element in battlefield success, commanders will tell you. Radio operators let other units and commanders know where their own units are, how they are doing, and if they need help—whether food, ammo or troop reinforcements.

And they often do it while in the thick of the fighting.

The gear that Phanthavong carries in the field weighs up to seventy pounds. “You have to carry crypto equipment (to make sure the enemy can’t intercept your communications), different kinds of cables and antennas, spare headsets, and a spare battery, which is really heavy,” he said. “You also have to carry your personal water and your personal ammo.”

He carries a double line of ammunition. “I consider myself a soldier first,” he said. “When you’re a radio operator, you need to be able to fight with the troops around you. And one of my biggest concerns has always been running out of ammo.”

Phanthavong’s latest assignment is with the Canadian Headquarters and Signal Squadron in Latvia—one of the countries on NATO’s eastern frontier. In addition to Latvian troops, he has been training with soldiers from Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Italy, Spain, Albania, and Montenegro.

“It’s been a very nice experience,” he said. “We exchange ideas with them, see how they work, learn how to achieve compatibility with them.”

The exchange is not just military, but cultural, he said. “It’s in the kitchen”—because different countries’ units have different food—and “in the local music provided to us,” he said.

He smiles at the memory of an exchange he had with a group of British soldiers in Afghanistan —the legendary Nepalese fighters known as Gurkhas.

“With my face, I look a little bit like a Nepalese,” he said. “They saw me in my Canadian uniform and stopped for a second with a look like, ‘What’s wrong with this guy?’” It suggested they were thinking that he didn’t look like any kind of Gurkha they knew.

“They are really tough,” said Phanthavong, who watched the Gurkhas at work. “They climb mountains like crazy with really heavy packs on their back.”

Phanthavong is not sure where his military career will ultimately end up. But his supervisors have noticed how good he is at explaining communications to younger soldiers one-on-one, so he could become an instructor.

A virtuoso on the violin

Five years ago, in his mid-30s, Phanthavong took up the violin as a way to relax. He became good enough to be asked to play at church services at Camp Adazi, Latvia, where he is now stationed.

Phanthavong began playing the violin as a way to decompress after work. “It’s kind of a moment to myself,” he said. “No matter where I am, it makes me feel like I’m home—because I started by playing at home.”

At the moment, he prefers playing classical music and epic themes like the one in the movie “Lord of the Rings.” But his repertoire will broaden soon to include religious fare. That’s because the priest at Camp Adazi—who agreed to Phanthavong’s request to practice at the base chapel because of its acoustics—was so impressed with his talent that he asked him to play at services. Phanthavong is thinking about making his debut on Easter Sunday.

In addition to soothing his soul, the violin has become a way of broadening his social circle. Some of the strangers who see his violin case and ask about his avocation become friends. One is a guitarist who wants to make a violin arrangement of a song he composed. Another is a woman who asked him to teach her the violin.

“It’s good to focus on the good things, the positive things”—and violin is one of the pluses in his life, Phanthavong said.

“I still have a lot of memories—including bad ones—from the refugee camps,” he said. “Everyone has problems in their life. It’s important to face them but also to focus on going forward.”

That approach has served him well in the military. And it’s likely to for the rest of his life.

Hal Foster is a freelance journalist based in Moldova.

Image: Master Corporal Khamphone Phanthavong lived in refugee camps in Thailand and Argentina be-fore coming to Canada when he was four years old. The ethnic Laotian is now a Canadian Army communications specialist. (Photo by Corporal Geneviève Beaulieu, Enhanced Forward Pres-ence Battle Group Latvia)