America’s most valuable contribution to democracy is and always has been the successful implementation of freedom at home. If our country had grown up in despotism, the world would be a different and far bleaker place.

Today, such attributes of the U.S. system as free and peaceful elections, an independent judiciary, civilian control of the military, diversity in positions of authority and an unfettered Internet and press remain a source of inspiration to others. The accompanying caution is that, especially in this plugged-in world, the power of our example will wax or wane in parallel with the performance of our institutions and the loyalty we demonstrate to our own ideals.

During the Cold War, Communist propagandists delighted in America’s slowness in guaranteeing equal rights to its minority citizens. Today, our example is undermined less by perceptions of discrimination than by the appearance of paralysis in addressing economic problems. Surveys indicate that the average Chinese is far more optimistic than the average American (or European) and that a majority of U.S. citizens believe our country is headed in the wrong direction. This must change.

The most salutary elixir for American democracy would be an end to the gridlock and pandering that now infect our politics and undermine effective decision-making. This will not happen overnight, but I believe that a backlash is building and that a more mature style of leadership will be rewarded by voters, refurbishing our country’s reputation and clearing the way for positive steps domestically and on the world stage.

Supporting democracy abroad requires both confidence and humility. The United States should never consider itself exempt from criticism or an exception to rules that apply to others. But neither should we be reluctant to draw a clear distinction between the merits of a democratic system and one characterized by illegitimate leaders and the chronic denial of human rights.

In promoting democratic values, there should be no limit to our hopes, but our actions should not extend beyond the boundaries of international law. Our policies should take into account the varying challenges faced by democrats in countries along the spectrum between free and unfree. Our methods should begin with moral suasion and the offer of a helping hand, augmented by our Allies and bolstered by partnerships with non-governmental organizations.

The State Department and USAID have excellent supportive programs, as do organizations affiliated with the National Endowment for Democracy (including the National Democratic Institute, which I chair). We should also strongly encourage investment and trade to enhance the economic prospects of fragile democracies.

For supporters of liberty, patience and impatience both have a place. We have learned that free institutions do not spring full-grown from any country’s soil. Most nascent democracies face an array of obstacles, including that of failing to meet lofty expectations. When that happens, the risk is high that charlatans will pounce, promising quick solutions in return for unrestrained power. In fact, a generation or more is typically required to instill habits of effective governance and to harvest the material gains that will lift standards of living.

A long-term view

Accordingly, outside assistance must be sustained over a period of years, and should include both development aid and guidance—where requested—on everything from the basics of public administration to the optimum role of civil society. At the same time, leaders who promise a democratic transition should not be allowed to ward off criticism by offering only token reforms. Is a country truly moving in the right direction or merely running in place? That is a question we should always be prepared to ask and answer.

Majority rule is democracy’s cornerstone but also its slippery slope. Populations divided by ethnicity, tribal connections, and religious beliefs may fall apart completely if voting is viewed as an all or nothing proposition. It is natural for those who lose elections to feel disgruntled, yet they should neither fear for their lives nor despair of the chance to do better in future balloting.

That is why the true test of democracy comes less with the first election than with those that come after. The development of an effective parliament is also crucial—both to enact laws and to provide a vehicle for opposition political parties to participate, find their voice, and hold leaders accountable.

For the same reason, the rights of individuals, and those of groups to which individuals belong, must be protected in any democracy, regardless of who prevails at the polls. Emerging democracies must have time to develop unifying characteristics—including a clear sense of nationhood and the formation, which is vital, of a middle class. The process of forging one country out of many factions may seem daunting, but it is rarely impossible. On this point, the experience of Europe and America is instructive, as is the miracle of India; if that land’s vast human canvas can thrive as a democracy, so too can any nation.

Discussion of democracy in 2012 and succeeding years will almost inevitably center on the Middle East and thus likely revive a familiar question: Is it wiser to support traditional leadership structures in the hope that they will produce stability or to encourage democratic openings despite uncertainty about where they will lead?

The temptation for policymakers will be to avoid a firm answer, reacting instead on a case-by-case basis. This tendency to hedge bets will be reinforced by pleas from regional leaders, each of whom has a vested interest in his country’s status quo. Such a hesitant approach will surely trail the pace of unfolding events and—although intended to minimize risks—actually constitute a gamble on wobbly principles and shaky regimes. People want democracy; the choice we face is to stand with those who block their way, or do what we can to clear the path.

The latter alternative—to make a firm commitment to democracy—may be faulted for promising consistency in a region where every country has its distinctive history, personalities, and culture. Yet failing to establish a general set of benchmarks would leave us without a coherent message at a time when the identities of those who speak up and those who remain silent may be remembered for generations.

Without exception, U.S. and Allied policy should be to support democratic governments and institutions, including the peaceful evolution of nondemocratic regimes. Such a policy should not be seen as abandoning the region’s more responsible monarchs, whose position may be accommodated within the framework of constitutional change. Popular representation can be achieved through a variety of means, but the basic right of public participation should be available to all who abide by democratic principles.

We should remember that the alternative to support for democracy is complicity in the rule of governments that lack the blessing of their own people. That policy would betray the Arabs who are most sympathetic to our values and reveal a preference for the sterile order of repression over the rich and self-correcting sustainability of a free society.

Sharing our values

Unless we truly believe that our principles and interests coincide, we can serve neither effectively. We must want for others what we most cherish ourselves: the right to choose our own leaders and to help shape the laws by which we are governed. Far more than any particular personalities or programs, it is that right that defines our claim to leadership and that constitutes the hope of the world.

Madeleine K. Albright was U.S. secretary of state from 1997 to 2001. She is the chair of Albright Stonebridge Group and Albright Capital Management LLC, as well as professor in the practice of diplomacy at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, and honorary director of the Atlantic Council. This piece is taken from the Atlantic Council publication The Task Ahead: Memos for the Winner of the 2012 Presidential Election.

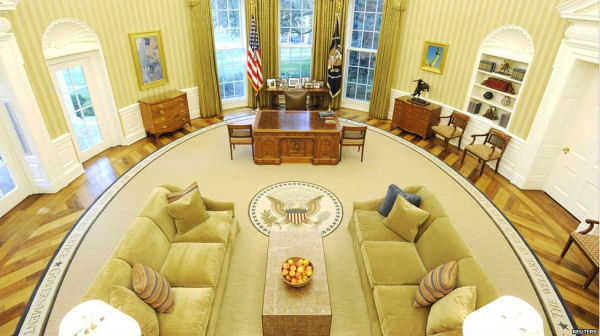

Image: oval-office-2010-new-overview.jpg