US President Donald J. Trump’s announcement that ISIS (ISIL, Islamic State, Daesh) “will be gone by tonight” is welcome news. An important battle in Syria has been won. But the war will continue. It will rage throughout the Muslim world until political legitimacy fills vacuums of governance that Islamist extremists will continue to contest; legitimacy that can only come about through the voluntary consent of the governed. This is a war for the hearts and minds of Sunni Muslims; not buildings and trackless desert.

ISIS was the child of al Qaeda in Iraq (sustained for years by Syria’s Assad regime) and supporters of the late Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein. ISIS first filled a governance vacuum in eastern Syria, one opened by the Assad regime’s decision to concentrate its forces against the popular uprising in the major population centers of the country’s west.

After declaring himself the caliph (successor) of the Prophet Muhammad, the Iraqi Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (a pseudonym) launched an invasion of his native country from Raqqa, the Syrian city designated by the faux caliph as his capital.

That invasion in 2014 brought the return of US forces to Iraq. An attempt by ISIS later that year to overrun a Syrian Kurdish city on the border with Turkey was repulsed by Kurdish militiamen and US combat airpower. The successful defense of Kobani led to an alliance between the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the US-led anti-ISIS coalition: an alliance that would (because of the YPG affiliation with the terrorist PKK, or Kurdistan Workers’ Party) cause a severe crisis between Turkey and the United States.

In Iraq, ISIS swept nearly unopposed over a large part of a country rendered defenseless by the corrupt, incompetent, and overtly sectarian rule of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. In Syria, ISIS developed a mainly live-and-let-live relationship with the regime of Bashar al-Assad. In both cases, ISIS benefitted from the belief of ordinary people that their nominal rulers had no right to rule.

As is the case when co-existing criminal gangs occasionally clash, ISIS and Assad came to blows now and then over money in the forms of natural resources and precious antiquities. It benefited both to depict the other as the mortal enemy. Their relationship was entirely symbiotic.

For Assad, ISIS was a gift from God: a cult whose elaborate atrocities could divert attention from his own regime’s systematic, Nazi-like elimination of imprisoned dissidents. Pretending to be the enemy of and the alternative to Baghdadi, Assad felt free (with Iranian and Russian help) to combine starvation sieges with the wholesale slaughter of civilians in non-ISIS areas by artillery and air attacks.

And for Baghdadi, Assad was his star recruiter: a person from Syria’s Alawite minority, supported by Shia Iran and Christian Russia, focusing state terror on overwhelmingly Sunni populations. Within Syria, ISIS focused its military prowess not on Assad, but on those who had rebelled against Assad’s rule. Each of these criminals wanted to be the only alternative to the other. Then, presumably, the final battle could be joined.

Assad and Baghdadi were, in short, the two mutually dependent faces of terror in Syria. To count ISIS as an “opponent” of the regime—at least until the real opposition to Assad could be neutralized by both—is to misunderstand profoundly the collaborative relationship between these criminal terrorist entities.

Is ISIS truly dead in Iraq and Syria? The answer will be in the hands of Iraqis and Syrians. Until these countries transition fully from the abyss of Maliki-Assad illegitimacy to systems reflecting—in their own ways—rule of law and the consent of the governed, a post mortem would be premature. Indeed, the US intelligence community believes thousands of ISIS fighters remain in Iraq and Syria.

Al Qaeda in Iraq—thought to be killed by the military and political proficiency of the 2007 US surge—used the Maliki-Assad cocktail of corruption and incompetence to resurrect itself in the form of ISIS. And the sheer longevity of ISIS in Iraq and Syria—aided by Western reliance on militiamen instead of military professionals in Syria—facilitated terror operations in Europe and inspired the proliferation of copycat, “franchise” operations in parts of the Sunni Muslim world as far apart as Afghanistan and Africa. But in Syria and Iraq, ISIS (or a rebranded version of the same thing) will not be dead until political legitimacy rooted in the consent of the governed confirms the death.

The same is true throughout the Sunni Muslim world. One struggles to name more than a handful of predominantly Sunni states where the consent of the governed is a factor—much less the controlling factor—in the operation of political systems.

In places where illegitimacy prevails, the deranged, dysfunctional, and disappointed—people lacking in piety and self-worth—can be attracted to politically ambitious criminal organizations offering purpose, privilege, dignity, and meaning shaped by a perverse interpretation of Islam that strips from the creed all reference to tolerance, kindness, mercy, charity, and human decency. Under the guidance of cynical, bloody-minded leaders, this legion of losers and misfits will continue to wreak havoc in the world of Islam and beyond, until it is snuffed out by legitimate governance.

Surely it is not the job of the United States to implant political legitimacy in the Arab or the broader Muslim world. And a measure of self-congratulation is indeed appropriate for the erasure of the “physical caliphate” in a remote corner of Syria. But Trump would also do well to ask and answer some questions.

Is the United States doing all it can in the Arab world and beyond to help develop the region’s greatest natural resource: its human capital? Promoting educational reforms so millions can function in the twenty-first century? Encouraging students from the Muslim world to attend US universities? Helping Arab and other governments remove internal obstacles to innovation and entrepreneurship? Rallying economic support for countries—like Tunisia—where legitimacy struggles to gain traction? Projecting a sincere, deep-seated respect for Islam? Convincing people around the world that rule of law, human rights, and the United States’ permanent struggle for “a more perfect union” have universal applicability and an honored place in US foreign policy?

It is, in the end, for Sunni Muslims to kill ISIS and keep it dead. Yet a West interested in defending itself will help. It will focus its help on human resources: on populations whose best and brightest have, for generations, left dead-end societies to grace Western democracies. Helping this enormous pool of repressed human talent acquire the skills and the resources needed to stay at home and to transform sterile economies and corrupt, top-down politics into systems worth supporting is the pathway to killing the fake caliphate forever. Weapons of war are surely essential in this struggle. But human capital—one way or the other—will be decisive.

Frederic C. Hof is a nonresident distinguished senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center and diplomat-in-residence at Bard College. Follow him on Twitter @FredericHof.

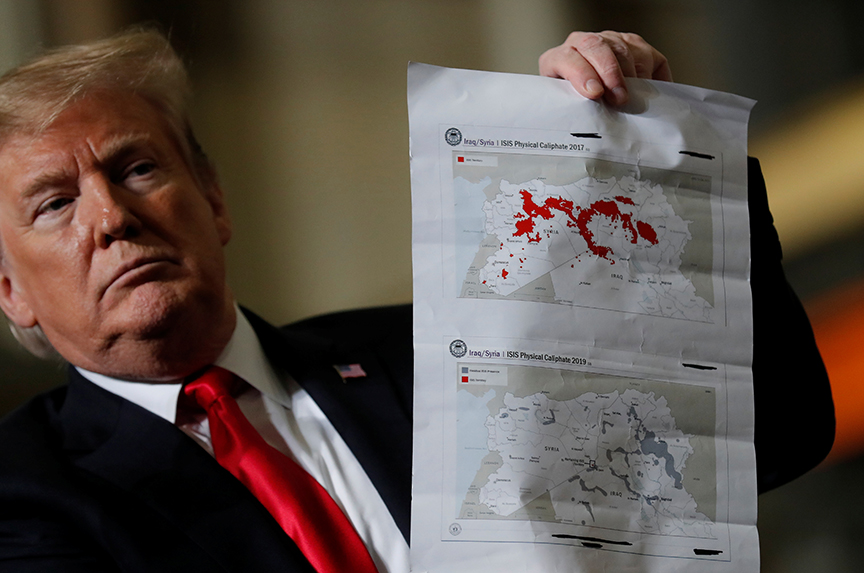

Image: US President Donald J. Trump showed maps of Syria and Iraq depicting the size of the “ISIS physical caliphate” as he spoke to workers while touring the Lima Army Tank Plant (LATP) Joint Systems Manufacturing Center, the United States’ only remaining tank manufacturing plant, in Lima, Ohio, on March 20. (Reuters/Carlos Barria)