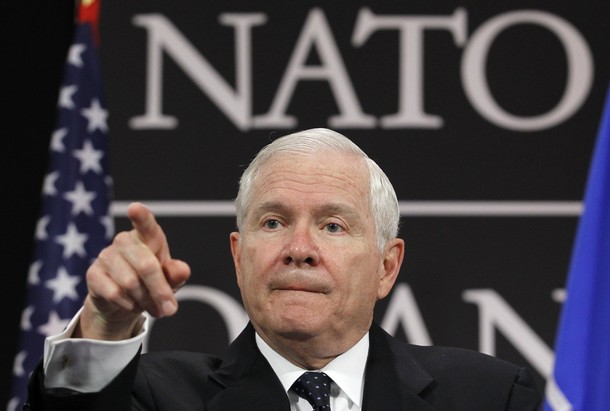

The “farewell address” delivered by outgoing Secretary of Defense Robert Gates to the North Atlantic Alliance last Friday was a stark warning that “business as usual” cannot continue much longer.

Jorge Benitez argued earlier this week that it should be seen as a call to arms: “Now is the critical time for supporters of the transatlantic alliance to make their voices heard within each NATO capital and hold their leaders accountable for protecting the military shield which has provided peace and secured prosperity since 1949. … NATO is our common defense and it has kept the peace for more than six decades. So let us argue and complain as brothers in arms. But let us also heed the warning from Gates and start making the tough decisions together.”

But I think that the lack of willingness to “make the tough decisions together” arises from more than lack of political will; it strikes directly at diverging views about the role and purpose of the alliance.

Gates’ remarks highlight the definitive failure of both Democratic and Republican administrations over the past decade to convince NATO to transform itself into a security organization with global reach. As I noted at World Politics Review: “It is not simply that many NATO allies refuse to spend more on defense; what they are spending on is just as much a problem. As Richard Weitz concluded, "[M]ost European militaries still spend excessively on capabilities related to territorial defense, rather than on those designed to meeting global challenges through expeditionary forces.

There are a number of reasons for this continued emphasis on territorial defense: an unwillingness, particularly now in times of economic hardship, to divert more resources from social welfare to defense spending; and a perception on the part of some allies that there are still significant threats in the immediate neighborhood — whether from a resurgent Russia to the east, the possibility of a resumption of the wars in the Balkans or instability arising from the south.”

But there is also a growing unwillingness in Europe to help the "indispensable nation" bear its global burdens—a fear that the U.S. will seek to shift the costs Washington has incurred on its partners. Canada’s decision to withdraw from the AWACS program and Norway’s announcement that it will terminate its participation in the air campaign in Libya are driven, in part, by fiscal considerations—so any sort of message that new defense spending is required to reduce the costs to the United States will not win much support.

I am also curious if there is an unspoken motivation behind this, with continued reluctance on the part of the European allies to commit to a more global role for NATO perhaps driven by a fear that a NATO that redefines its mission in global terms, and that develops the capabilities to project power as a result, will draw the alliance into a role in containing China. A "global NATO" that combines the Euro-Atlantic core with partners like Australia, Japan, and India will not be able to justify its raison d’etre by simply providing humanitarian assistance to all corners of the globe. And China is now the only credible near-peer military competitor to the U.S. During the Cold War, Europeans were more than willing to help contain a Soviet Union whose hegemonic aspirations threatened their own peace and security. But a China that becomes dominant in East Asia is not necessarily a problem for Europe, and some Europeans may not want to be drawn into a U.S.-China rivalry in the Pacific basin.

So Benitez (and Gates), in the midst of their pessimism, express the hope that the alliance can renew itself going forward. But I can’t share that glimpse of optimism.

Nikolas K. Gvosdev, a contributing editor at the Atlantic Council, is professor of national security decision making at the U.S. Naval War College.

Image: reuters%206%2011%2011%20Roberts%20Gates%20NATO1.jpg