The condemnations came swiftly on the night of the attempted coup. From critics of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s human rights record to Selahattin Demirtaş, the head of the opposition Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), to Russian President Vladimir Putin and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the consensus was clear: military coups bring misery. The history of Turkey, as well as that of Algeria and Egypt, holds cautionary tales. The military has intervened four times in Turkish politics—in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997. Nobody wants Turkey to go down that path again.

The condemnations came swiftly on the night of the attempted coup. From critics of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s human rights record to Selahattin Demirtaş, the head of the opposition Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), to Russian President Vladimir Putin and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the consensus was clear: military coups bring misery. The history of Turkey, as well as that of Algeria and Egypt, holds cautionary tales. The military has intervened four times in Turkish politics—in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997. Nobody wants Turkey to go down that path again.

But failed coups, too, are dangerous. In 1993, a tense standoff between Russian President Boris Yeltsin and parliament was resolved when Yeltsin resorted to the use of military force. This was followed by a change of the Russian constitution, a super presidency, and a weakened legislature. These are exactly the changes that Erdoğan has been calling for since last summer.

Hours after a faction of the military took up strategic positions in Ankara and Istanbul on the night of July 15, Erdoğan called on the Turkish people to take to the streets. “This uprising is a gift from God to us because this will be a reason to cleanse our army,” he said. In the twenty-four hours after the start of the coup, some 3,000 members of the armed forces were detained.

By July 17 Justice Minister Bekir Bozdağ confirmed that 6,000 people had been detained. That number is expected to rise. On July 16, some 2,700 prosecutors and judges were dismissed. Ten members of the high council of judges and prosecutors and two members of the constitutional court, the highest judicial institutions in Turkey, were arrested.

Members of the military and the judiciary have been accused of acting on behalf of US-based religious leader Fethullah Gülen whom Erdoğan promptly blamed for the violence and for trying to set up a parallel state. Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim has declared that “any country that stands by the Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen will not be a friend of Turkey and will be considered at war it.” For months, the Turkish government has been pressing the United States to deport Gülen to face terrorism charges in Turkey. Those calls have gone unheeded.

Erdoğan may hope to have gained new international capital after the failed coup. Over the past few weeks he has successfully reconciled with Russia and Israel. Turkey’s relations with Russia and Israel had been frozen since 2015 and 2010, respectively. Cooperation between Turkey and the United States has also become more visible in operations against in Syria and Iraq.

Erdoğan went after the usual suspects soon after the attempted coup. Members of the military as well as the judiciary have been under pressure for years, first between 2008 and 2011 because they represented the strongest vestiges of the Kemalist establishment and since 2013 because of alleged ties to Gülen. The independence of the judiciary was already threatened earlier this summer following a nationwide shakeup of thousands of judges and prosecutors.

Erdoğan and his advisers are usually quick to blame external forces for any instability, claiming such action is aimed at destroying the Turkish republic. If Washington resists calls to deport Gülen, the anti-US and anti-EU tone in Turkey is likely to grow stronger. Until now, Erdoğan’s government has rarely taken steps against US or EU soft interests in Turkey. That could change.

The coup attempt was unexpected. For the past several weeks the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and the PKK have been seen as the main security threats facing Turkey. It remains unclear who attempted the coup, with what intentions, and why now. Many observers, like Soner Çağaptay, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, are predicting that it will lead to new crackdown on dissent and opposition.

Most worryingly, since the night of July 15, Erdoğan has instructed Turks to go out into the streets and mosques around the country are calling on people to defend the state. This time around, the repression may not only be carried out by police and prosecutors but also by newly empowered masses supporting the national will. Turkey today is a highly polarized country. There is a real risk that the attempted coup can become a spark alighting this tinderbox unless people are reeled in and institutions able to regain their authority and democratic effectiveness.

One institution that has remained steadfast to its democratic mandate so far is parliament. After being bombed earlier in the morning on July 16 representatives of the four parties in parliament—the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), the Kurdish issue-focused HDP, and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP)—issued an unprecedented joint declaration condemning the coup attempt “against our mighty nation.”

It may be unlikely, but if this spirit of cooperation is nurtured Turkey may be able to return to peace talks between the state and the PKK that were suspended last year. An estimated 600 troops, 338 civilians, and 6,000 PKK forces killed over the past twelve months. If Erdoğan can restart peace talks that would be a positive coup for Turkey.

Sabine Freizer is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center and Transatlantic Relations Program.

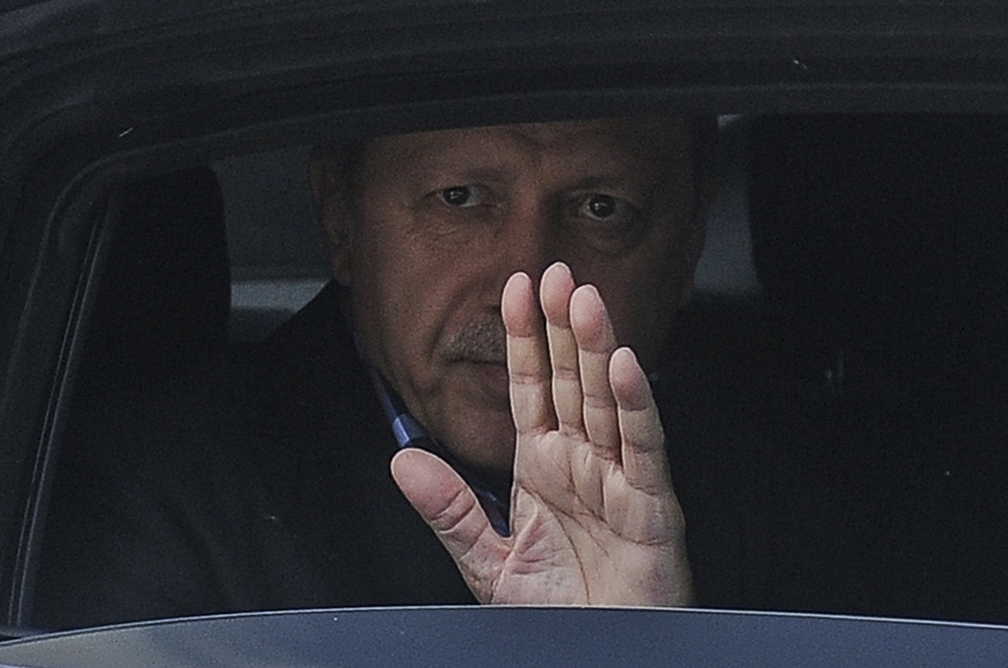

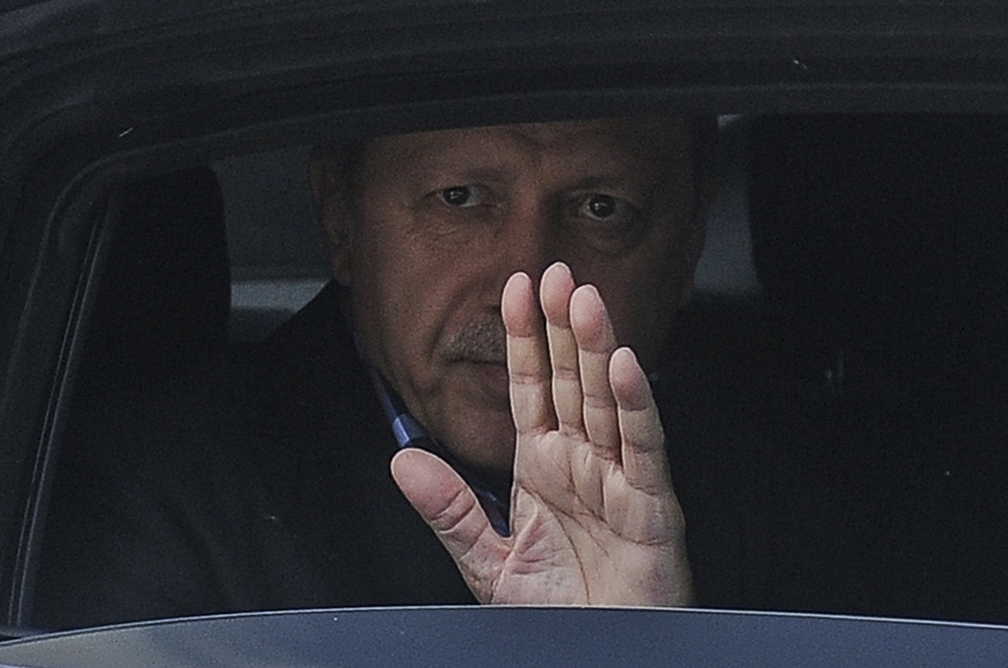

Image: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan waves from his car after leaving his residence in Istanbul to attend a funeral service for the victims of a foiled coup at Fatih mosque in Istanbul, Turkey, on July 17. (Reuters/Yagiz Karahan)