I do not recall the exact day but it was surely in early August 1963 that Harold King, the iconic Bureau Chief of Reuters’ bureau in Paris called me in, and he was not best pleased. I thought it was I who had invoked his impressive ire, but it was news from London.

“The buggers want to offer you Berlin,” he growled. It was flattering that he should not want me to leave after only 18 months in crisis-torn Paris, but West Berlin was an unmissable chance. It had a staff of four under the veteran German Alfred Kluehs. It would be good to work under him, I ventured.

“Not West Berlin, idiot,” grumped the Paris Chief. “East Germany.”

My heart did one of those chicane swerves. It was a one-man bureau, so that meant Bureau Chief. I was still just 24. The parish east of the Iron Curtain comprised East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. It was huge and, apart from its three national armies, contained three Soviet army groups.

All three countries had harsh regimes, vicious secret police apparats and about one Western correspondent – the Reuters man. But the core was East Berlin, glowering and snarling behind the recently erected Berlin Wall. This was the absolute height of the Cold War, nine months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the general agreement was that if World War Three and mutual wipe-out ever came, Berlin would probably be the spark.

Forty-six years later a word of explanation is in order. After 1945 the Reich was divided into four zones: American, British, French and Russian, between the east and the west the Iron Curtain went up. But Berlin, set 110 miles inside East Germany, was subject to a different treaty and though divided into four sectors, was decreed an open city. For East Germany that was virtually a death sentence.

West Germany shrewdly decreed that while she would refuse the validity of East German degrees in politics, philosophy, history etc (communist propaganda) she would accept degrees in maths, physics, chemistry, engineering and so forth. Between 1945 and 1961, tens of thousands of young East Germans waited until they graduated, then grabbed a bag, took the train to East Berlin and simply walked into the West. Once in West Berlin they would be flown down the air corridor to a new life and career in the West.

East Germany had been industrially and comprehensively raped by the USSR with most of her assets put on trains heading east. Now the cream of her youth was simply draining away towards the West. Finally, in August 1961, working 24 hours a day and with Soviet agreement, they put up the Wall and closed the last aperture.

The reaction of the West was volcanic. Everyone knew why they had to do it, but that was not the point. The Wall broke every treaty on the city of Berlin. NATO led the charge. Every embassy was closed, every diplomat and trade delegation withdrawn. And that meant foreign correspondents. All the East German press people in the West were expelled, including the ADN (East German News Agency) woman in the Reuters building in Fleet Street.

But the East German Politburo made one exception. They might pump out bilge to their own people but they wanted to know what was really going on in the world, so, without any quid pro quo, one Western reporter was allowed to stay. The Reuters man. Thus, after a fortnight of intensive briefing in London, I sat on a sultry September night staring down from the elevated rail line as the Paris-Warsaw train eased out of West Berlin and trundled into the East. And then I looked down on the Wall.

Some think it was a straight line. Not at all. It switched and swerved from the city limits on the north side across the divided city to the south. But always in sharp angles, never a soothing curve. Back then many abandoned apartment blocks still stood on the east side, very close to the Wall. They were compulsorily abandoned, with west-facing windows bricked up, later to be demolished to create an open killing ground. But then the demolitions were not finished. These were the buildings from which desperate heroes tried to jump to freedom only to die on the wire, in the minefields or under machine-gun fire.

Seen from above there was a dark city and a blazing city and between them the brilliantly illuminated, snaking Wall. And the train rumbled into East Berlin’s main station.

I was met by my predecessor, Jack Altman. He had taken a year of it; the bugging, the watching, the eavesdropping, the following, the knowledge that everyone he talked to would be interrogated. It had got to him. He was stressed out, hyper-tense. I shared the office/apartment with him for three days, then he was gone, still seeing Stasi (secret police) agents behind every kiosk.

I determined I was not going down that road and, although bi-lingual in German and with adequate Russian, I affected with officialdom a cheerful, Bertie Wooster ineptitude and a strangled accent. Even the leather-coated Stasis I made a point of greeting loudly across the street with unquenchable good humor. It drove them potty. But… you wish to know about the Wall. Let me recall three incidents.

As a foreigner, my crossing point into West Berlin was the famous Checkpoint Charlie. Those who recall the opening scenes of the Richard Burton film The Spy Who Came In From The Cold may wonder if it was really like that. Yes, on a bitter winter night under the arcs, it was just like that. Menacing.

On November 22, 1963, I was dining in West Berlin with a glorious girl when the muzak stopped and a grim voice said in German: “Achtung, achtung. Hier ist eine Meldung. President Kennedy ist erschossen.” (“Attention, attention. Here is an announcement: President Kennedy has been shot and killed.”)

At first nothing happened. There was a jolt in the babble as if someone had said something particularly silly. Kennedy was a demi-god in West Berlin. He had visited in June. He had guaranteed their protection. He had said he was a Berliner. Then the message was repeated.

Chaos. Pandemonium. Hysteria. Women screaming, men swearing in a continuous torrent of oaths. I threw a fistful of D-Marks on the table, asked the girl to settle up (not that anyone was going to worry about asking for the bill) and ran for my office car by the kerb. It was an East German car, a Wartburg, often daubed with insults by West Berliners who presumed I must be a high-ranking communist to have permission to come over.

Checkpoint Charlie was like the Marie Celeste. The GIs, stunned, stared out of their booth but did not emerge. The East Berlin barrier swung up eventually and I reported to the Custom shed. Never had I, nor did I since, see those arrogant young guards, chosen for their fanaticism, so utterly terrified.

Even back then, before email, texting, or any knowledge of cyberspace, you could not block out the radio waves. They all listened. They all knew. They begged me to assure them there would not be war. And this was before we learned that Lee Harvey Oswald was a communist, had defected to the USSR and been sent back. When that came through, even the Foreign Ministry begged me to tell the West it was not their fault. That evening on the Wall, edging towards midnight, the only Westerner at the crossing, surrounded by near-hysterical border guards, wondering if one would see the dawn, is one I will not forget.

Harold King had trained me well. The training cut in. I raced back to the office and started to field the torrent of calls from equally terrified East German officialdom. I filed a story but I don’t think it ever saw print. That night it was Dallas, Dallas, Dallas.

A month later, the East Berlin authorities relented in their complete ban on West Berliners entering East Berlin. Many of those who had fled were young, but Papa and Mutti had remained behind. For some reason Pankow (the government suburb) decided to let visitors in for Christmas reunions. It was supposed to be a propaganda triumph. Actually, it just underlined the brutality of the concrete monster that kept people apart.

The allocated crossing point was the Chausseestrasse crossing and at the appointed hour a huge seething mass of citizenry appeared on both sides. Both sets of authorities lost control. Young West Berliners were trying to find relatives while buffeted officials tried desperately to examine their passports. A hundred George Smileys could have slipped through and that had the Stasis in hysterics.

Wanting to get the feel of this mass of humanity, I hopped on a car bonnet, then the roof and from there to the top of the Wall. Then I walked down it to the edge of the crossing zone. I had a British sheepskin car coat (the temperature was ten below) and a Finnish wolf fur hat. Very sexy. And very spooky, it seems.

Cameras began snapping unseen from east and west. I do not know how many agencies have a picture of me towering over the chaotic mass of humanity, pushing and shoving at the crossing point that afternoon, but it was a great story and, as I was the only one there, an exclusive for Reuters. Head Office sent me a congrats on the story and a warning, which I think came from MI6, not to play “silly buggers.”

Eventually a squad of hysterical East German People’s Police stormed up to grab me off the Wall. I came down, putting on my Bertie Wooster what-have-I-done-wrong act and they let me go. I went home and filed the story.

Not quite so funny was the occasion I nearly started World War Three. To this day I protest it was not entirely my fault.

For a young Westerner, private life was a social Sahara – even meeting and conversing with someone from the free world could mean, for an East Berliner, a snatch and interrogation by the Stasis. But there was one place that was usually lively late at night – the Opera Café.

So one night, April 24, 1964, at about one in the morning, I was driving home when, at a junction, I was stopped by a Russian soldier planted foursquare in the road, back to me, arms spread. As I watched, a massive column of Soviet military-might rolled past; guns, tanks, mechanized infantry bolt upright in their trucks… I spun round and tried another road. Same result; column after column of Soviet armor and I realized it was all heading straight for the Wall.

Twisting and turning down the blackened back streets I made it to my office, then typed and sent the story. I did not exaggerate; I did not explain because I had no explanation. I just reported what I had seen. Then I brewed a strong black coffee and sat by the window to wait for dawn.

All across Europe the ministry lights were going on. The British Foreign Secretary was dragged from his bed. In Washington, the Defense Secretary was whisked from a dinner in Georgetown. It took two hours and some frantic messages to Moscow to sort it out.

It was one week to May the First and the silly bastards were rehearsing the May Day Parade. In the middle of the night. Without telling anyone. With the mystery explained a large number of bricks rained down on Reuters’ man in East Berlin. Well, how was I to know? No one else did.

I left East Berlin that October after 13 months. Quietly, with my car parked by my office. Alone, walking with a single grip through Checkpoint Charlie. Once safely

in the West I could fly out of Tempelhof to London.

The fact is, I had been having a torrid affair with a stunning East German girl. She explained she was the wife of a People’s Army corporal, based in the garrison at faraway Cottbus on the Czech border. She was an amazing lover and rather mysterious.

She was immaculately dressed and after our almost-all-night love sessions at my place refused to be driven home, insisting on a taxi from the railway station. I wondered about the clothes, and the money for taxis. One day I spotted one of the drivers at the station whom I had seen at my door picking up Siggi. He said he had taken her to Pankow. That was a very upscale address, the Belgravia of East Berlin. On a corporal’s salary?

It was in a bar in West Berlin that two buzz-cut Americans who screamed CIA slid over to offer me a drink. As we clinked they murmured that I had a certain nerve to be sleeping with the mistress of the East German Defense Minister.

It was not the minister I worried about as I drove back through the Wall. It was his political enemies who would love to arrange his downfall and a show trial for me. Time to go. A week later I walked through the Wall for the last time.

I saw its destruction in November 1989 on television. But I was there October 1, 1990, the formal reunification of the two cities and the two Germanys. I noted that a team of workmen was at Checkpoint Charlie – turning it into a tourist attraction. So I went to a bierstube, ordered half a liter of Schultheiss and raised it in their general direction. Cheers, it was a fascinating year behind the Wall.

Frederick Forsyth is a best-selling author, whose works include The Day of the Jackal and The Fourth Protocol.

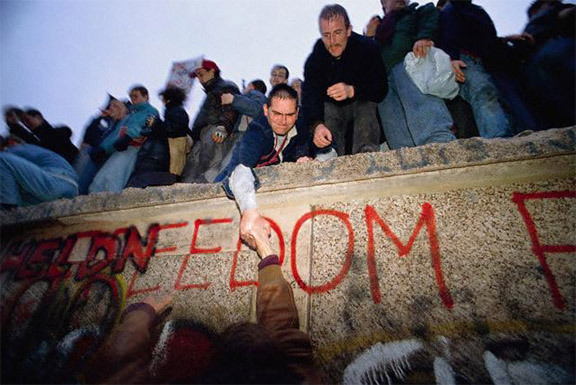

This piece is selected from Freedom’s Challenge, an Atlantic Council publication commemorating the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Image: Berlin%20Wall%20Freedom_0.jpg