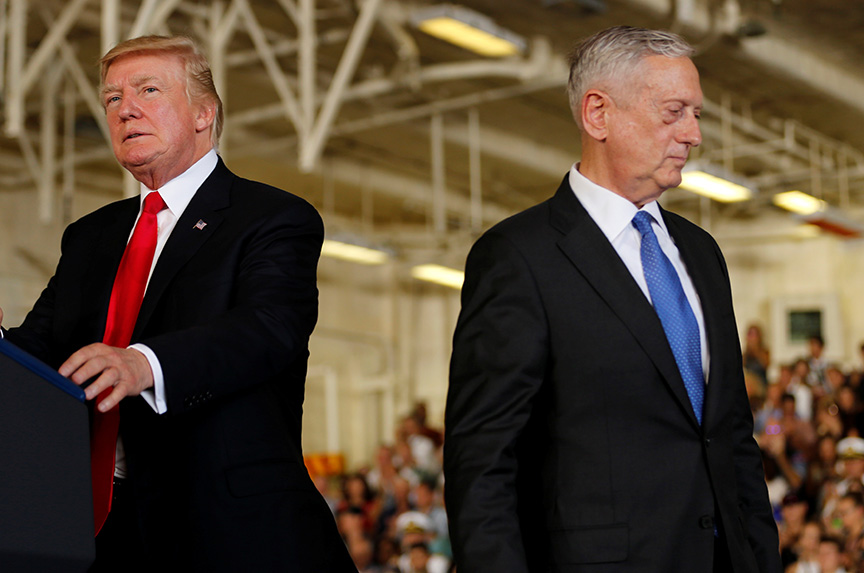

If US President Donald J. Trump moves to replace Secretary of Defense James Mattis after the midterm elections in November, as he has signaled his want to do, the effect will be significant for government decision-making at home and for our defense activities abroad.

A post-Mattis Department of Defense (DoD) will align more closely with the president’s worldview and act accordingly. We can expect more muscular and high-risk military posturing, alliances coming under new strain, and the United States’ reputation for unilateralism deepening.

Trump ramped up speculation of his intent to fire Mattis when he said during an October 14 interview on 60 Minutes that his secretary of defense is “sort of a Democrat” and soon “may leave” the Pentagon. Should he leave, Trump will have replaced his national security advisor (twice), secretary of state, secretary of defense, and CIA director within the first two years of his presidency (his first CIA director became his second secretary of state). There also have been a number of changes below the Cabinet-level, to include letting go and then eliminating the positions of his White House homeland security advisor and cybersecurity coordinator. Only his original Director of National Intelligence and Treasury secretary will have survived as plank holders of the first-half of the Trump administration’s war Cabinet.

High-level departures are major transition events for departments and agencies. Front office teams are shuffled. Senior leaders and staff expend considerable amounts of time preparing briefing materials for the incoming team. Coffees are had with incoming advisors. New alliances are formed.

Different influence dynamics alter current and planned resource and mission priorities. Secretaries have their own information-processing style and executive secretariats spend a stunning amount of time getting her or his sign off on how many pages per briefing memo, what is the preferred font, how much background information is necessary, where it goes in memos, and how far in advance packages must get to the secretary for action. Then the new rules must be conveyed across the building. For DoD, this is a vast and complex endeavor. Next come substantive briefings, calibration of policy, and the full gamut of introductory phone calls, meetings with foreign counterparts, and first reviews of troops and trips abroad.

One of the most important dynamics for new Cabinet officials is relations with the president. Substantive smartness and hard work are no guarantees for good ties with the president and national security advisor. Former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson never established a rapport with Trump and his close ties with Mattis and Director of National Intelligence Dan Coates did nothing to fix this core problem. Not being able to connect with the president doomed Tillerson well before he lost the support of those inside the State Department. Tillerson’s successor, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, has proved masterful at cultivating the president and diplomacy has quickly regained some luster within the White House.

There is wide-ranging reporting about Mattis’ cool relationship with the president, well beyond what was written in exposes like Bob Woodward’s Fear and Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury. Mattis has earned plaudits in the Pentagon for largely shielding the military from the president’s more radical and inchoate proclivities. He successfully slow-rolled the president’s desire for a military parade down Constitution Avenue, ban of LGBT personnel from the armed forces, and even assassinating Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad. Mattis solidified his independence when he expressed admiration for the troops, not Trump the person, during a bizarre televised Cabinet meeting in June 2017. Mattis’ reportedly rocky relationship with current National Security Advisor John Bolton also contributes to the distance between DoD and the White House.

But has Mattis’ independence been good for our national security writ large and the DoD in particular? As someone who believes in the calibrated use of force, operating in concert with allies to the maximum extent practicable, thoughtful planning, and respect for the rule of law, I am happy Mattis so often out maneuvered this White House. But as a matter of course, and in normal times, our civilian secretary of defense must be in sync with, and compliant to, the president.

What might a more simpatico and pliant secretary of defense mean for our national security and international relations? One on hand it will smooth decision making in Washington. Pompeo’s close rhetorical and policy alliance with the president has made him a reliable voice of the president. Other nations certainly are comforted knowing the secretary of State actually speaks for the president. It gives coherence and consistency to what is said and what is done. Having a secretary of defense in similar alignment with the president will add more coherence and credibility for allies and adversaries to her or his words.

Substantively, we can expect a more aligned secretary of defense to be more assertive in tone and quicker to deploy (and employ) force abroad. Trump has given DoD a wide berth under Mattis on resources and the execution of force. Mattis has been judicious in the application and show of force, if not in pursuit of more overall federal spending for bigger, stronger, faster weaponry. We could expect a different secretary of defense acting to reinforce Trump’s rhetoric and quick, impulse decision making to be far more likely to press for missile and missile defense platforms abroad, directly challenging Chinese patrols in the East and South China Seas, and tearing up more restraint regimes like the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces and Open Skies treaties. We also could expect more intemperate remarks about allies and NATO. Of greatest concern would be a new secretary treating presidential tweets as policy guidance and orders.

It is not clear when Mattis will leave the Pentagon. What is clear is that his departure will usher in a more conforming leader compliant to this particular president’s unusual and impulsive leadership style. That’s not good.

Todd Rosenblum is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. Follow him on Twitter @ToddRosenblum1.

Image: US President Donald J. Trump (left) and Secretary of Defense James Mattis attended the commissioning ceremony of the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford at Naval Station Norfolk in Norfolk, Virginia, on July 22, 2017. (Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)