Nine months after NATO’s summit in Wales, and with less than a year to go before NATO’s next gathering in Warsaw, the Pentagon’s highest-ranking officer in Europe says the 28-member alliance stands ready to confront any threats it may face.

Nine months after NATO’s summit in Wales, and with less than a year to go before NATO’s next gathering in Warsaw, the Pentagon’s highest-ranking officer in Europe says the 28-member alliance stands ready to confront any threats it may face.

Lt. Gen. Frederick “Ben” Hodges, Commanding General of the US Army Europe, labeled Russia’s recent military incursion into eastern Ukraine “unacceptable in the 21st century.” He also praised what he called “a unity that I have not seen in my thirty-five years in the army”—despite Russian President Vladimir Putin’s efforts to create friction within the defense alliance, which dates back to 1949.

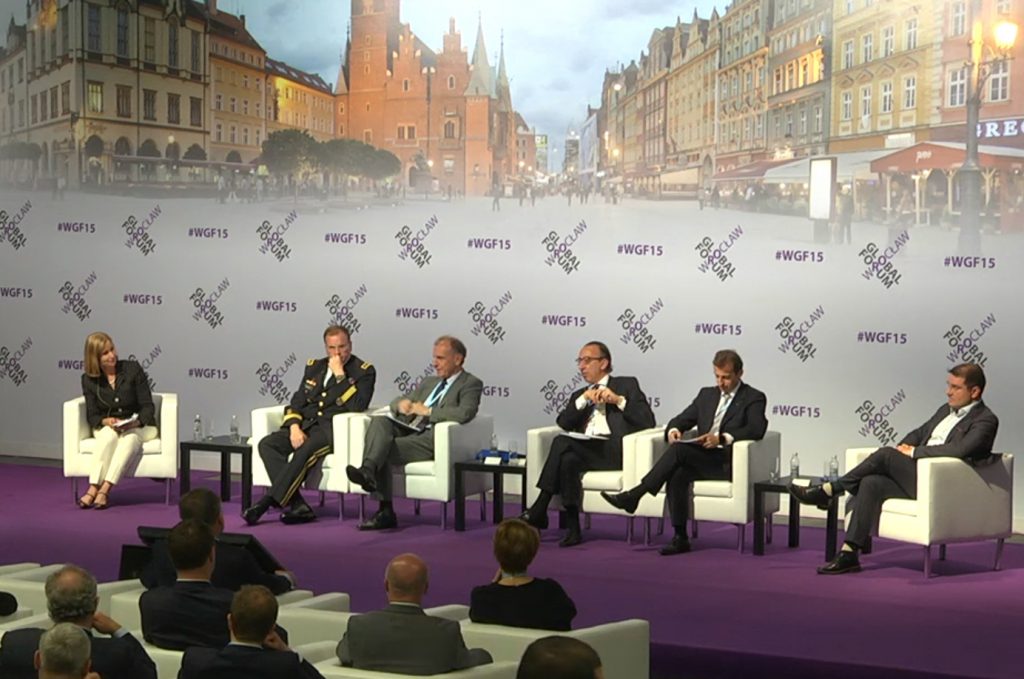

Hodges spoke June 12 during the Atlantic Council’s Wrocław Global Forum 2015 in Wrocław, Poland. He shared a panel with Jorge Domecq, Chief Executive of the Brussels-based European Defense Agency (EDA); Guillaume Faury, Chief Executive Officer of Airbus Helicopters; Bogdan Klich, Poland’s former Defense Minister, and Olaf Osica, Executive Director of the Center for Eastern Studies.

Paula J. Dobriansky, Senior Fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center, moderated the discussion, titled “From Wales to Warsaw: Transatlantic Defense Between the Summits.”

Klich, who is a member of the Polish Senate, said the model of security that has determined NATO’s priorities over the last two decades has disappeared.

“On the southern flank of our community, we now have the emergence of several new factors. One of them is the creation of [Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham] and a new wave of terrorist threats,” he said. “This is a completely new environment, creating a new challenge for Europe.”

Domecq said this “new security environment,” which has emerged since the last European Council defense meeting in December 2013—when the hottest topic was the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan—makes the need for EU-NATO cooperation more urgent than ever.

“The issue of defense matters even more now,” he said. “We made a commitment at the Wales summit to increase our defense spending. But it’s not only about increasing spending. Even going above 2 percent doesn’t fix the issue.”

Domecq, a Spanish diplomat who has led EDA since February, said NATO’s European members cannot keep spending half of what US taxpayers spend on the alliance, while producing only 15 percent of the Pentagon’s output.

“We cannot continue to have nineteen different types of armored fighting vehicles and the US has one, or fourteen types of battle tanks where the US has one,” Domecq said. “The only way to get through this is enhanced cooperation. And for that, it is essential that Europe has a strong, integrated industrial base to preserve our technological edge on the battlefield.”

Osica, whose Warsaw-based think tank is fully funded by the Polish government, was even more blunt.

“We need deeds, not words. We’re all very good at making commitments and adopting strategies and blueprints, but in our environment we need to show we are serious about our commitments,” he said, adding that NATO must forge a “double-track approach” that protects Europe while keeping open vital channels for cooperation and cooperation with Moscow.

“Among some of NATO’s European members, public opinion does not support Article 5,” he said, in reference to the treaty which considers an attack on one NATO ally an attack on all of them. “This comes back to the question of capabilities. The farther west we go, the less people are willing to contribute to NATO’s Article 5 defense.”

Yet that elicited a rather sharp retort from Hodges.

“I completely disagree with the implication that NATO is about words, not deeds,” said the Lieutenant-General, who last December ordered one hundred Abrams tanks and Bradley Fighting Vehicles into Eastern Europe to deter what he called Russian aggression. “We’re not perfect, but for sixty-five years it has been the most successful military alliance in the history of the world. You don’t get to be that way and accomplish the mission of deterrence by just talking about it.”

Larry Luxner is an editor at the Atlantic Council.

Image: From left: Paula J. Dobriansky, Senior Fellow at Harvard University and Atlantic Council board member, moderates a June 12 panel, “From Wales to Warsaw: Transatlantic Defense Between the Summits,” with Lt. Gen. Frederick “Ben” Hodges, Commanding General, US Army Europe; Bogdan Klich, former Polish Defense Minister; Jorge Domecq, Chief Executive of the European Space Agency; Gullaume Faury, CEO of Airbus Helicopters, and Olaf Osica, Executive Director of the Center for Eastern Studies. The event was part of the Atlantic Council’s Wrocław Global Forum 2015 in Wrocław, Poland.