At the Munich Security Conference last week, I moderated a panel discussion that posed an intriguing question: can we make [economic] competitors like the United States, Europe, and China trade again?

That we should ask such a question at a conference that wants to “contribute to the peaceful resolution of conflicts by sustaining a continuous, curated and informal dialogue” is an oddity.

For decades, trade has been the number one way for countries around the world to peacefully co-develop, build ties, and produce wealth, and it has been enormously successful at that.

Globalization has enabled billions of people to become part of a global trading system and to be lifted out of poverty. And trade has reduced, not increased, the gap between rich and poor globally.

The overall impact of trade conflicts has been to put a strain on global trade. Already declining as a percentage of GDP since 2008, trade growth is now adversely affecting economic growth.

At Davos, the International Monetary Fund lowered its forecast for global growth, citing trade tensions. “Higher trade uncertainty will further dampen investment and disrupt global supply chains,” said its chief economist, Gita Gopinath.

That should not come as a surprise. Trade is not a weapon, and trade wars often lead to a lose-lose situation. “Winning” them can simply not be done without harming both sides.

Consider in this regard some misconceptions on global trade, as elaborated by the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on International Trade and Investment.

The Council recently demonstrated that trade deficits aren’t bad per se, that bilateral trade between countries doesn’t have to be balanced, and that deficits don’t have to mean job losses or lower economic growth.

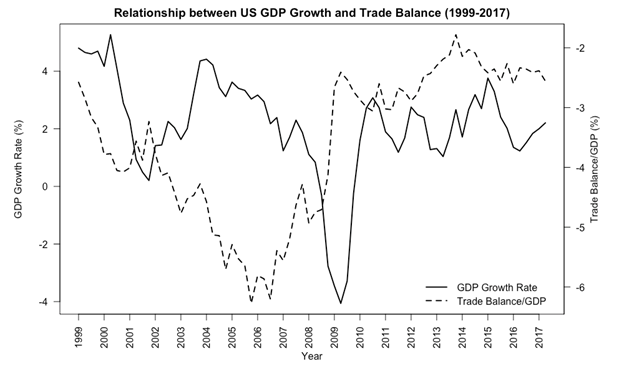

Their arguments for these statements can be read in full in the paper. As evidence, consider that US employment growth historically grew alongside imports, and that GDP growth was higher as the trade balance was lower (see below).

Figure 1: Relationship between US GDP growth and trade balance, 1999-2017

In the face of such evidence, and of other statistics that show that global trade has been an unparalleled motor for global prosperity, we should know better than to use trade as a weapon.

Manufacturing supply chains and monetary markets are so integrated that taking one-sided measures to alter them can have grave unintended and harmful consequences.

If countries take measures to import less, for example, their demand for foreign currency is likely to fall. So, their own currency is likely to appreciate, and their exports become more expensive, pricing them out of the market.

Instead, a better focus would be to make sure that trade benefits are spread more equally within nations, and that it serves to create more equitable and inclusive economic growth.

The responsibility here lies primarily with policymakers who deal with large multinationals, and with companies acting in the interest of all their stakeholders. Governments have the mandate and the power to correct the market; they should use it more decisively again.

My own country, Norway, may serve as an example on how to do that. As trade, environment and foreign minister, I helped craft policies that belong to what we’ve come to call “The Nordic Model.”

That model entailed opening the economy and embracing free trade, while implementing policies that protect workers and ensure there is a strong social safety net and healthcare for all.

In an environment where all citizens, both private and corporate, are encouraged to do their part by working productively and paying taxes, these measures have meant a win-win for all. Scandinavian countries are among the wealthiest, most equal and most open in the world.

In recent years, and during the session I moderated at the Munich Security Conference, we heard and saw what the alternative would be: trade wars leading to reduced prosperity at best, or a hardening of geopolitical tensions and possible real war at worst.

Faced with this choice, it should be obvious which route we should choose. Trade is not a weapon, and waging war isn’t in anyone’s interest. Let’s improve globalization, not do away with it.

Borge Brende is president of the World Economic Forum. Follow him on Twitter @borgebrende, and the World Economic Forum @wef.

Image: US Vice President Mike Pence shook hands with German Chancellor Angela Merkel during the annual Munich Security Conference in Munich, Germany, on February 16. (Reuters/Michael Dalder)