The November 15 announcement by the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the designation of seventeen Saudis for their role in the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi should be commended. While the Trump administration has been delayed in responding to the murder, with the president slowly forming a “very strong opinion,” the sanctions demonstrate that the administration has not stood idly by.

Given the need for continued cooperation with the Saudi government on counterterrorism, oil production, and a host of other sensitive issues, the Global Magnitsky (or GloMag in sanctions parlance) sanctions authority was a strategic tool to use as part of a response to the Khashoggi murder.

Treasury’s use of the GloMag sanctions authority exemplifies precisely what that authority was created for—it is a targeted action intended to punish specific targets without broader negative implications.

In the eleven months since it was established, the GloMag sanctions authority has been used to designate 101 individuals and entities involved in human rights abuse or corruption. While the malign activity of these targets was sufficiently abhorrent to warrant targeted sanctions, in many cases the United States continues to maintain diplomatic, economic, security, or other relationships with the host nations where these targets are located.

The targeted nature of the GloMag sanctions authority renders it dynamic enough to impact the individuals and entities involved in human rights abuse and corruption without disproportionately impacting foreign governments, allies, or their domestic populations.

What is the Global Magnitsky Sanctions Authority?

In late December 2016, the US Congress passed the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act. This was the second law named for Russian whistleblower Sergei Magnitsky who died while in a Russian prison after being tortured and denied medical care. The newer law expands upon the original Magnitsky Act by broadening the scope of the legal authority for economic sanctions and visa bans related to human rights abuses and corruption to global actors. This was a significant broadening since the original Magnitsky Act was focused solely on Russia.

The Global Magnitsky legislation was signed into law in December 2016 but was not used until one year later when the Trump administration built on this legislation to launch a new sanctions regime targeting human rights abusers and corrupt actors globally through Executive Order (E.O.) 13818 “Blocking the Property of Persons Involved in Serious Human Rights Abuse or Corruption.” E.O. 13818 also includes the authority for economic sanctions and visa bans.

As with other OFAC-administered sanctions, any designation pursuant to this authority results in the blocking of the designated individual’s property or interests in property within or transiting US jurisdiction. In the inaugural tranche of sanctions under this new authority, the administration made a strong statement against human rights abuse and corruption globally. The administration generally continues to wield the tool in impactful ways, including in the announcement related to the Saudis.

MbS: A Glaring Omission?

While the November 15 designations make a strong statement about holding those responsible for Khashoggi’s murder accountable for their actions, the exclusion of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) is conspicuous, and Congress is certain to take note.

Congress recently called on the administration to apply the GloMag authority in response to the Khashoggi murder, with some in Congress advocating for including MbS in any sanctions action. Such an inclusion was always unlikely due to US President Donald J. Trump’s transactional view of the US-Saudi relationship, as well as the potential repercussions.

Instead, the sanctions included more politically palatable targets, with the most senior official being Saud al-Qahtani, a former adviser to the royal court. The US announcement also included al-Qahtani’s subordinate, Maher Mutreb, and Saudi Consul General Mohammed Alotaibi, the senior official at the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul where Khashoggi was murdered, as well as fourteen other Saudi government officials who participated in the planning and execution of the operation that led to the October 2 killing.

In an announcement likely coordinated with the United States, the Saudi government noted the same day that al-Qahtani has merely been banned from travelling and remains under investigation, while twenty-one other people are now in custody, with eleven indicted and referred to trial.

Neither the US nor the Saudi announcement implicated MbS, though US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin caveated the OFAC action by noting that “the United States continues to diligently work to ascertain all of the facts and will hold accountable each of those we find responsible,” leaving the door open to possible additional sanctions or other actions.

Additional potential actions are already being actively discussed. Senate Republicans are advocating for the suspension of negotiations with Saudi Arabia on a nuclear technology sharing agreement, though Trump indicated he is unlikely to support this.

In October, a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced a bill in the US House of Representatives to stop most US arms sales to Saudi Arabia. While the bill is unlikely to get traction during the lame duck Congress, the Trump administration is also not poised to support it given the president’s previous statements in favor of the highly-touted $110-billion arms package for Saudi Arabia.

Equally unlikely to gain the president’s support would be any action specifically targeting MbS, including sanctions. Any such decision would have to be seriously weighed against the broader potential costs to the US-Saudi relationship. The United States would also need to possess irrefutable evidence of his role in the Khashoggi killing—something US National Security Advisor John Bolton affirmed earlier this week the United States does not have.

Historically, the United States has refrained from designating heads of state where the likely costs of such an action outweigh the messaging benefits—such as in the case of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The United States also delayed designating North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro until it was assessed that the benefits of each action outweighed the costs. Similar thoughtful discretion will likely continue to be applied with regard to any action targeting MbS.

Samantha Sultoon is a visiting senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program and the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. She is a former sanctions policy expert for the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

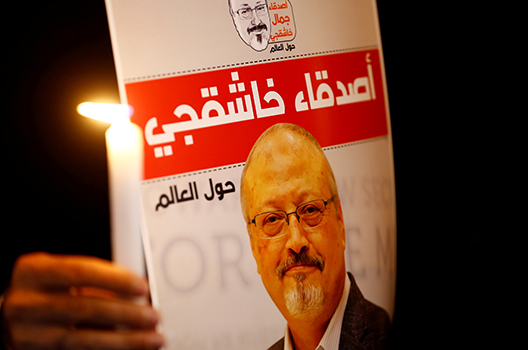

Image: A demonstrator held a poster with a picture of slain Saudi journalist, Jamal Khashoggi, outside the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, on October 25. (Reuters/Osman Orsal)