It has been a long time since I have sensed any cause for optimism about the prospects of a political settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Indeed, Armenia and Azerbaijan nearly resumed full-scale war in April, when their troops clashed along the line of contact with a level of ferocity unprecedented during the twenty-two years since the previous ceasefire. As the dust has settled, however, two new openings have emerged, one rather unexpectedly from Russian President Vladimir Putin and another from a regional business leader. Both merit Washington’s close examination and perhaps its embrace.

It has been a long time since I have sensed any cause for optimism about the prospects of a political settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Indeed, Armenia and Azerbaijan nearly resumed full-scale war in April, when their troops clashed along the line of contact with a level of ferocity unprecedented during the twenty-two years since the previous ceasefire. As the dust has settled, however, two new openings have emerged, one rather unexpectedly from Russian President Vladimir Putin and another from a regional business leader. Both merit Washington’s close examination and perhaps its embrace.

The background for Putin’s recent proposal is a draft framework agreement tabled by the US, Russian, and French co-chairs of the OSCE’s Minsk Group in 2007. Known as the Madrid Document, it proposes the following package of elements as the framework for a political settlement:

- Armenia returns all seven territories it seized from Azerbaijan during their war in the early 1990s;

- Nagorno-Karabakh receives an “interim legal status,” which preserves the current political and economic realities governing the region’s Armenian residents until determination of the region’s “final legal status”;

- Nagorno-Karabakh’s “final legal status” will be determined by a vote of Nagorno-Karabakh’s population at a time still to be decided;

- A transit corridor will be established to link Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia;

- International peacekeepers will provide security to residents of Nagorno-Karabakh and villages along the line of contact; and

- Azerbaijan lifts all transit restrictions between Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and the rest of Azerbaijan.

These principles resulted from several years of negotiations among the presidents and foreign ministers of Azerbaijan and Armenia. Though this framework was never formally agreed upon, in January 2009, Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev and Armenia’s President Serzh Sargsian did express optimism that they could eventually be accepted in principle.

In late 2009, however, Sargsian walked back his position and accepted in principle the return of only five territories to Azerbaijan. This dispute over the return of five versus seven territories has been the core obstacle to progress in Minsk Group negotiations ever since.

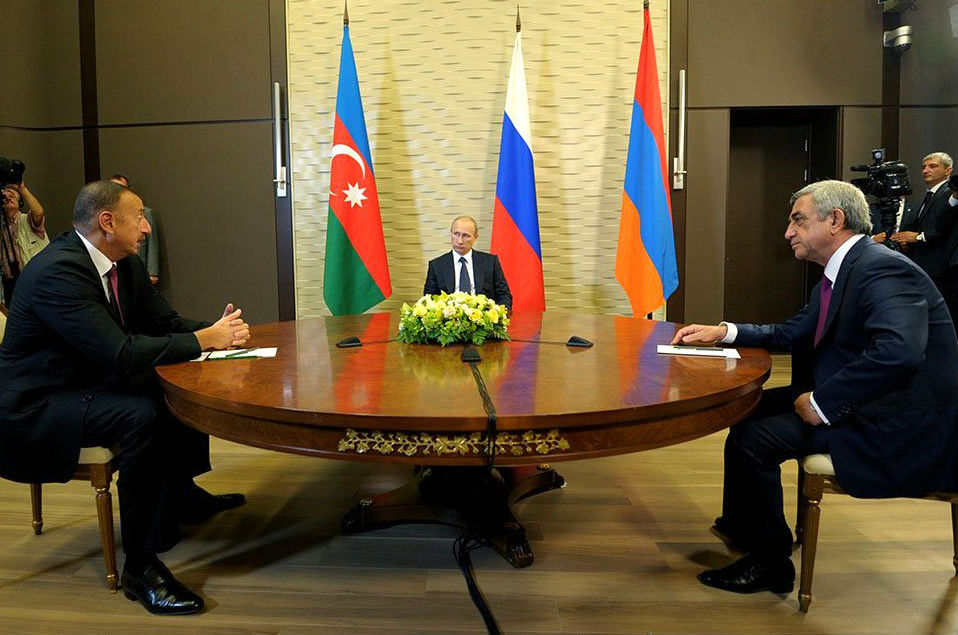

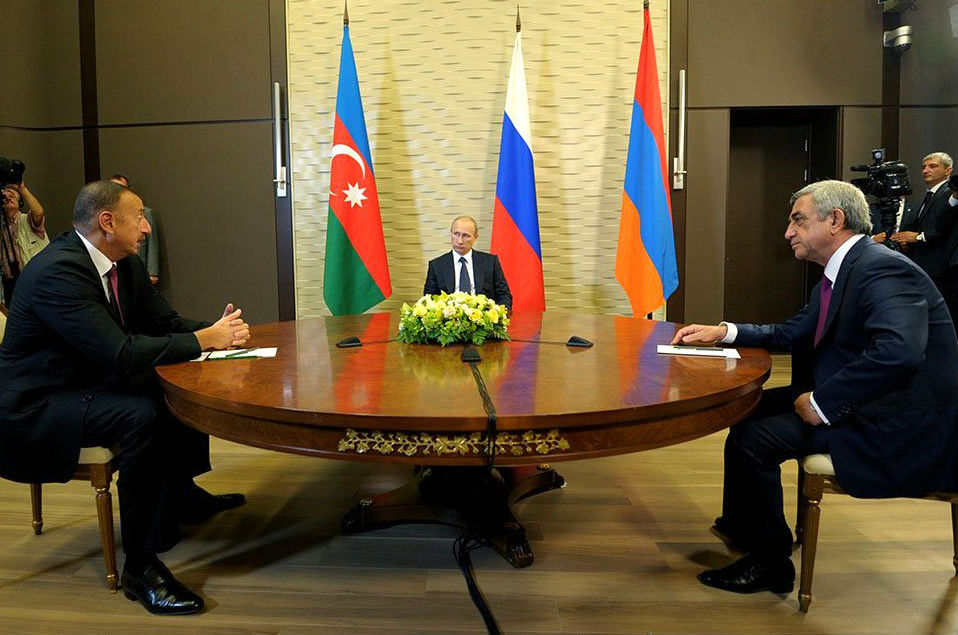

On June 20, Putin proposed a way to break this impasse during a meeting with his Armenian and Azerbaijani counterparts. Putin apparently suggested moving incrementally forward, with Armenia returning just two territories in exchange for Azerbaijan resuming normal transit and economic connections to Armenia; all other aspects of the Madrid Principles, including the remaining five occupied territories, would be subject to further negotiations.

Both Sargsian and Aliyev have welcomed Putin’s June 20 proposal, even if they have not formally accepted it. Official acceptance of any compromise is fraught with political and security risks for both presidents due to a climate of mutual hatred that current and former politicians in both societies exploit.

Given such risks, it is probably no coincidence that on July 17, an armed group of Armenian nationalists, including veterans of the Nagorno-Karabakh war, seized a police station in Yerevan, killing one police officer and taking several hostage. The group demanded the release of a right-wing politician and longtime critic of Sargsian’s handling of Minsk Group negotiations. The siege attracted vocal support from other Nagorno-Karabakh hardliners, leading to street clashes with police. The standoff lasted for fourteen days, until the hostage-takers surrendered.

Hardline attitudes are equally prevalent in Azerbaijan. I have asked many Azerbaijani university students how they would react if one of their friends befriended an Armenian; they have consistently said that they would react with suspicion, hostility, and disgust. I was verbally attacked by several Azerbaijani parliamentarians, who called for me to be declared persona non grata for advocating compromises with Armenia.

It therefore requires a great deal of courage for anyone in Azerbaijan or Armenia to advocate moving beyond demonizing the other country. Yet a self-made billionaire who was born in Azerbaijan and has served in Russia’s upper house of parliament, Farkhad Akhmedov, recently issued a courageous and heartfelt call for peace. I met Akhmedov in 2011, when he approached me during my tenure as the US Ambassador to Azerbaijan to ask how he might contribute to the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process. His recent appeal, which appeared in several Russian and Azerbaijani newspapers this month, reflects a desire to open minds and reduce mutual hatred in both Azerbaijan and Armenia to enable a settlement of the conflict.

Akhmedov’s open letter begins by addressing the Azerbaijani and Armenian peoples as “brothers and neighbors.” He laments, “An entire generation grew up in a climate of mutual hatred and hostility, not knowing it is possible to live in a different way….” and poignantly observes that “the battlefield…has entered the souls of each and every Azerbaijani and Armenian. War has crawled into our existence. It has become an everyday routine.”

Looking for a way forward, Akhmedov paraphrases Albert Einstein’s aphorism, “Weak people seek revenge; strong people forgive.” This formulation touches a nerve in Akhmedov’s native Azerbaijan, where a thirst for revenge against the victorious party in the Karabakh war, Armenia, is omnipresent. He nevertheless pushes a bit further, observing that international mediation of the conflict can succeed “only if we ourselves will be able to show courage and take the first step,” then opines, “As I understand it, the question of the affiliation of Karabakh has the following answer: it belongs to both nations.”

Though anathema today to both Azerbaijani and Armenian society, Akhmedov’s final formulation is the key to a political settlement of the conflict. Nagorno-Karabakh does belong to both nations, each of which views the region as a cradle of its respective culture; the two spent most of their histories living peacefully together.

Although it will take time for public opinion in Armenia and Azerbaijan to accept this notion of Nagorno-Karabakh as both nations’ common heritage, Akhmedov’s letter may have broken new ground: it received 500,000 responses on Facebook the day after it was issued. Speaking from my personal interactions with Akhmedov, I know his motivations are transparent and straightforward. He has achieved success in business beyond anyone’s wildest dreams and wishes to give something back by contributing to the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process.

Putin’s motives are certainly less philanthropic than Akhmedov’s. Putin’s June 20 proposal may be driven by a desire to appear to be a peacemaker on Nagorno-Karabakh rather than a warmonger in Ukraine. Or maybe Putin was genuinely rattled by how close Armenia and Azerbaijan came to full-scale war in April, which would have derailed his strategy of keeping separatist conflicts in the Eurasia region simmering but not boiling over. In any case, Washington should call what may be Putin’s bluff and seize the opportunity he has provided to revitalize the Minsk Group at the highest political level.

Washington should also embrace Akhmedov’s courageous call for Azerbaijanis and Armenians to set aside their last three decades of hatred and realize his dream of seeing, as occurred during his childhood, “an Azerbaijani and an Armenian again having a quiet conversation, enjoying a cup of tea, and playing a game of backgammon in the shade of a Karabakh sycamore.”

Matthew J. Bryza is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center. He was the US co-chair of the Minsk Group from 2006 to 2009 and US Ambassador to Azerbaijan from 2011 to 2012.

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin (center) held a trilateral meeting with Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev (left) and Armenian President Serzh Sargsian (right) in Sochi on August 10, 2014. Credit: Kremlin.ru