George Bernard Shaw quipped that the United States and England were two nations divided by a common language. Since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks that precipitated the global wars against terror and in Afghanistan and Iraq, Shaw’s observation has considerably broadened.

Are differences between both sides of the Atlantic on threats and dangers so great as to be potentially unbridgeable?

Evidence for this pessimism couldn’t have been in better display than this past weekend at the German Marshall Fund’s seventh annual Brussels Forum. The fund was established by the German government to honor of U.S. General of the Army George C. Marshall and his extraordinary achievements during and after World War II.

Attended by several hundred participants, many with high-level government service including serving members of the U.S. Congress as well representatives of European governments, the disconnects in critical trans-Atlantic views were vivid.

The largest and potentially most divisive was an answer to “what is the threat.”

An earlier, late night session on “Are we still from Mars and Venus?” coincidentally set the stage for what followed the next day. The reference was to a 10-year-old academic debate over whether Americans reflected Mars, the God of War, and Europeans Venus, the Goddess of Love, in approaching defense and security. Defense spending was one measure for making this assessment.

For most trans-Atlantic states, defense spending is in decline and some say in freefall. A major issue is rate of decline. China and Russia have taken opposite tacks by increasing defense spending.

Many Europeans see little in the way of existential military threats. While Russia is proposing to increase its defense spending, its army is no match for NATO despite the trepidations felt by several newer alliance members. On the western side of the Atlantic, especially with neoconservatives who got it wrong before over Iraq, these increases raise the specter of another cold war with global reach.

Iran and its nuclear ambitions are also oceans apart in trans-Atlantic thinking. No one wants a nuclear armed Iran. However, on the European side of the Atlantic among observers who are sober and knowledgeable, the only thing worse than a nuclear Iran is going to war to prevent that end state from occurring. Missile defense is part of this debate that also entangles Russia.

The conference’s concluding panel on the forthcoming U.S. presidential elections did more than capture these vast differences in outlook.

The panelists’ discussion and descent into a full campaign mode exchange of barbed one-liners and sound bites, shocked and infuriated many Europeans by its shallowness. Perhaps worse, the intractability and inflexibility of the two opposing U.S. political parties reinforced the perception that the United States was losing the ability to govern and thus to lead the trans-Atlantic community.

Former Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty, who is also a former presidential hopeful, and U.S. Rep. Linda Sanchez, D-Calif., took the stage for this session. Both are highly attractive and articulate. Individually, each can make very strong arguments supporting their side.

But together, the campaign took over.

While the debate remained civil, the exchanges of barbs and sound bites substituted for bold ideas. Indeed, more than one observer concluded that, based on this session, one of America’s political parties had lost its mind; the other its soul. Beholders could determine which party was which.

Pawlenty and Sanchez were asked to identify specific policy actions to address major issues such as fixing entitlement programs and making real tax reform — areas that both parties agree need to be addressed with urgency.

No answers were forthcoming. Sanchez said Republicans were intractable on raising taxes. Pawlenty countered that Democratic refusal to take spending cuts seriously was the source of all evil.

Unfortunately, the two were correct.

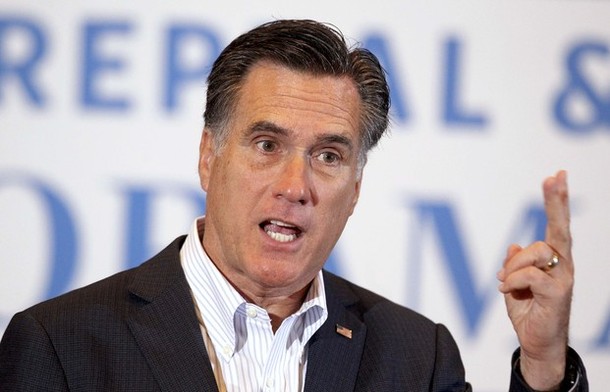

Pawlenty also promised that a President Mitt Romney would never allow Iran to develop nuclear weapons. The implication was that a Romney administration would use force to destroy Iranian nuclear facilities.

However, the logic of that position wasn’t pursued since the only certain way Iran could be kept from obtaining those weapons was by ground assault and occupation. Does candidate Romney understand that?

And to provide more military muscle, President Romney would add 100,000 ground forces and four additional carrier battle groups — expanding U.S. power in contradistinction to Europe’s direction.

What did participants take away from the Pawlenty-Sanchez exchange? The most charitable explanation was that this final panel got trapped by the presidential elections and was in full campaign mode. Americans were mostly embarrassed. Europeans weren’t. They were angered and some stunned.

Self-quoting is often dangerous. With that caveat, the title of an earlier column came to mind — that this panel was “desperate but not serious,” raising the question of America’s seriousness. And if that question is appropriate, both sides of the Atlantic are in serious trouble.

Harlan Ullman is senior advisor at the Atlantic Council, and chairman of the Killowen Group that advises leaders of government and business. This article was syndicated by UPI.

Image: romneyspeech.jpg