Operation Khanjar, a massive show of force in Helmand Valley, has kicked off today in what may be the last chance for the success of the NATO mission in Afghanistan.

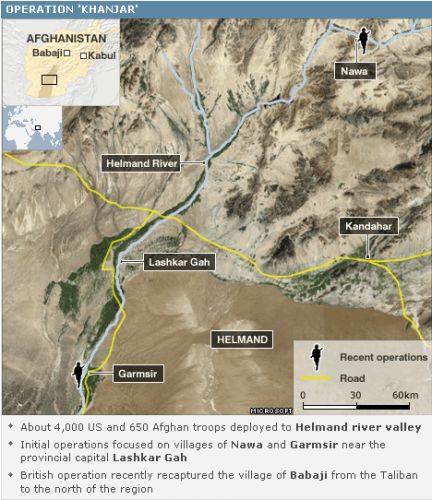

BBC, which Anglicizes the mission as “Operation Strike of the Sword,” passes on word from military spokesman Captain William Pelletier that there has been “no enemy contact” in the early going but that “one marine was slightly injured when an improvised explosive device detonated in the village of Nawa.” The story supplies the helpful map below:

Rajiv Chandrasekaran reports in both FT and WaPo that the mission “required months of planning” and is “the Marines’ largest operation since the 2004 invasion of Fallujah.”

The operation will involve about 4,000 troops from the 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, which was dispatched to Afghanistan earlier this year by President Obama to combat a growing Taliban insurgency in Helmand and other southern provinces. The Marines, along with an army brigade that is scheduled to arrive later this summer, plan to push into pockets of the country where Nato forces have not had a presence. In many of those areas, the Taliban has evicted local police and government officials, and taken power.

Once Marine units arrive in their designated towns and villages, they have been instructed to build and live in small outposts among the local population. The brigade’s commander, Brig. Gen. Lawrence D. Nicholson, said his Marines will focus their efforts on protecting civilians from the Taliban, and on restoring Afghan government services, instead of a series of hunt-and-kill missions against the insurgents. “We’re doing this very differently,” Nicholson said to his senior officers a few hours before the mission began. “We’re going to be with the people. We’re not going to drive to work. We’re going to walk to work.”

[…]

The operation launched early Thursday morning represents a shift in strategy after years of thwarted US-led efforts to destroy Taliban sanctuaries in Afghanistan and extend the authority of the Afghan government into the nation’s southern and eastern heartlands. More than seven years after the fall of the Taliban government, the radical Islamist militia remains a potent force across broad swathes of the country. The Obama administration has made turning the war around a top priority, and the Helmand operation, if it succeeds, is seen as a potentially critical first step.

It is mostly a U.S. Marine effort, as desired reinforcements from the Afghan army and the U.S. State Department have failed to materialize.

Despite commitments from the State Department and the US Agency for International Development that they would send additional personnel to help the new forces in southern Afghanistan with reconstruction and governance development, State has added only two officers in Helmand since the Marines arrived. State has promised to have a dozen more diplomats and reconstruction experts working with the Marines, but only by the end of the summer.

To compensate in the interim, the Marines are deploying what officers here say is the largest-ever military civilian-affairs contingent attached to a combat brigade – about 50 Marines, mostly reservists, with experience in local government, business management and law enforcement. Instead of flooding their area of operations with cash, as some units did in Iraq, the Marine civil affairs commander, Lt. Col. Curtis Lee, said he intends to focus his resources on improving local government.

Writing for AP, Fisnik Abrashi and Lara Jakes are more direct about the domestic political angle, noting, “Southern Afghanistan is a Taliban stronghold but also a region where Afghan President Hamid Karzai is seeking votes from fellow Pashtun tribesmen.”

WSJ‘s Yochi Dreazen notes the obvious: “The operation has no guarantee of success.” He explains:

U.S. commanders have telegraphed for months that they planned to flush the Helmand River Valley with American troops, so Taliban fighters had ample time to move to other parts of the country.In Iraq, similar operations generally failed to have much of an impact on the war effort, because fighters typically melted away into surrounding areas rather than taking on the large, well-armed American force. Successive U.S. operations in volatile Diyala Province, for instance, failed to find or kill many Sunni fighters there.

An unsigned piece in the London Times is more blunt:

In swiftly seizing the valley, commanders hope to accomplish within hours what Nato troops had failed to achieve over several years, and by doing so turn the tide of a stale-mated war in time for an Afghan presidential election on August 20.

CNN notes that the sheer scale of the operation is unusual.

In Washington, a senior defense official said the size and scope of the new operation are “very significant.”

“It’s not common for forces to operate at the brigade level,” the official said. “In fact, they often only conduct missions at the platoon level. And they’re going into the most troubled area of Afghanistan.”

As AFP‘s Ben Sheppard reports, the operation’s leadership are all too aware of the obstacles:

“This is a big, risky plan,” Nicholson told his men at a briefing at Camp Leatherneck in the run-up to the launch of the battle.

“It involves great risks and amazing opportunities. These are days of immense change for Helmand province. We’re going down there, and we’re going to stay — that’s what is different this time.”

Richard Oppel of NYT explains why the mission planners think it can succeed:

The British have had too few troops to conduct full-scale counterinsurgency operations and have often relied on heavy aerial weapons, including bombs and helicopter gunships, to attack suspected fighters and their hideouts. The strategy has alienated much of the population because of the potential for civilian deaths.

Now, the Marines say their new mission, called Operation Khanjar, will include more troops and resources than ever before, as well as a commitment by the troops to live and patrol near population centers to ensure that residents are protected. More than 600 Afghan soldiers and police officers are also involved.

“What makes Operation Khanjar different from those that have occurred before is the massive size of the force introduced, the speed at which it will insert, and the fact that where we go we will stay, and where we stay, we will hold, build and work toward transition of all security responsibilities to Afghan forces,” the Marine commander in Helmand Province, Brig. Gen. Larry Nicholson, said in a statement released after the operation began.

The last part of that is critical, as NPR‘s Tom Bowman points out.

“We’re never going to have — even in our wildest dreams — we’re never going to have enough Marines and soldiers to be everywhere,” he said in an interview. “That’s why having the locals take more responsibility in their own — hey this is my neighborhood, and I’m going to defend this neighborhood.”

(Bowman’s piece is well worth a read — and a listen — for its profile on Nicholson, who was seriously wounded in Iraq.)

Aside from the sheer scale of this new push, a key difference is the degree to which safeguarding against civilian casualties is at ingrained into the planning. AFP’s Sheppard:

Unmanned aerial surveillance would keep watch overhead while loudspeakers would keep local people informed, they said.

Brigadier General Muhayadin Ghori, the senior Afghan general involved in Operation Khanjar, told the briefing of senior US officers that they must “always work with the elders, even if they have grey hair.” “They are the ones with all the experience,” he said.

“I hope you will deliver the expectations that are on you,” he declared in an impassioned speech. But he warned that any repeat of the civilian casualties that have undermined the international military’s reputation among Afghans would be disastrous. “One casualty of a child will give everyone a bad name,” he said. “We should give priority to civilian casualties and then look after our own wounded soldiers.”

That’s a truism of counterinsurgency warfare going back generations. Finally, it seems, the mission planners are paying it heed. It will, however, come at the price of more Marines killed and wounded.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council. Photo: David Gilkey/NPR.

Image: BG%20Barry%20Nicholson.jpg