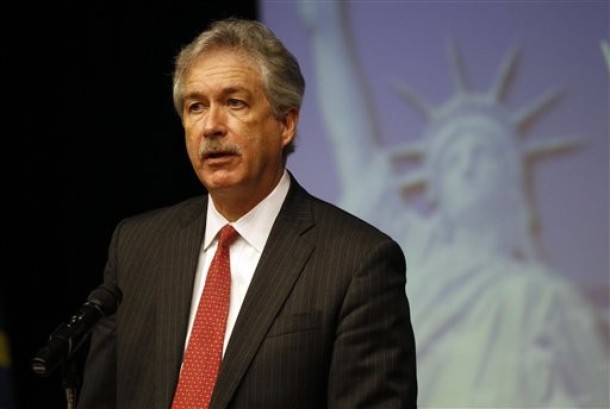

Deputy Secretary of State William J. Burns is a rare breed in Washington — a career foreign-service officer in a job typically held by political appointees and a man esteemed by both Democrats and Republicans. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who kept Burns on as undersecretary of state and then promoted him to his current job last July, has called Burns “a one-person brain trust when it comes to policy and diplomacy.”

Burns has many areas of expertise, including serving as ambassador to Russia from 2005-2008. But his experience in the Middle East is especially deep. Under the George W. Bush administration, he was among those who worked to promote Arab-Israeli peace after the 1991 Gulf War. He then served as ambassador to Jordan from 1998-2001 and assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern Affairs from 2001 until 2005. Although his current position means he literally covers the globe, Deputy Secretary Burns remains deeply engaged on Middle Eastern issues, in particular the challenges and opportunities of the Arab Spring.

What follows are responses from Deputy Secretary of State Burns to a range of questions from Al-Monitor Washington correspondent Barbara Slavin:

Slavin: How does the US avoid aggravating what appears to be a sectarian conflict in Syria by calling for Assad to go? Won’t the Alawite community circle the wagons even more around Assad, especially if the plan calls for a Sunni vice president?

Burns: We believe it is clear that Assad and his regime — not the opposition or the international community -— is the greatest driver of sectarian tension in Syria today. The best way to resolve those tensions is for Syrians to get beyond this despotic regime. It is our policy to help the Syrian opposition to move beyond such divides toward a democratic, inclusive, pluralist Syria that protects the rights of all Syrians, regardless of their background.

Toward that end, we and our international partners have encouraged the Syrian National Council and other opposition groups to reach out to all segments of Syrian society, including the Alawites, to include them in their organizations and to commit to protecting their fundamental human rights in post-Assad Syria. We have been encouraged by their response. They have reached out to minorities and articulated a national covenant for an inclusive Syria in which all citizens of Syria will enjoy human rights and fundamental freedoms irrespective of their affiliations, ethnicity, belief or gender. There is much work left to do in reassuring the Alawites, Kurds, Christians, Druze and others that they have a place in the new Syria. We will continue to urge the Syrian opposition to expand their outreach, to engage in a national conversation across Syria and to put into place a concrete transition plan that can further reassure all Syrians.

Slavin: [UN Special Envoy] Kofi Annan said Assad has promised to withdraw Syrian troops and heavy weapons from population centers by April 10 — why should we believe that and what will be the consequences if he doesn’t?

Burns: After many disappointments, we are naturally very skeptical of Bashar al-Assad’s promises. He has made similar promises over the past year to the Turks and to the Arab League, among others, but he has broken them all. As Secretary Clinton said in Istanbul, “The world must judge Assad by what he does, not by what he says.” We hope that Assad fulfills his promises, but given the record of the past year, we are not waiting to act. We are ratcheting up the pressure through new sanctions against regime officials and through establishing an accountability initiative to support and train Syrians working to document atrocities, identify perpetrators and safeguard evidence for future investigations. We are further isolating this regime, cutting off its funds and squeezing its ability to wage war on its own people. We are also expanding our humanitarian assistance — already over $25 million — to the people of Syria.

If the Assad regime does fail to follow through on his commitments, we will once again look to the international community and especially to the UN Security Council to fulfill its responsibility to help protect the Syrian people.

Slavin: Judging from Secretary Clinton’s comments in Istanbul, the US and much of the international community is looking for a Yemen-type solution in Syria that will remove Assad but keep state structures largely intact. Is that so and isn’t there a danger that the longer this conflict goes on, the more Syrian institutions will unravel and the more support will flow to extreme Salafist and al-Qaeda type groups? How serious are Saudi and Qatari proclamations of armed support for the Syrian opposition? Is this a good idea? Isn’t the US moving in that direction with its provision of “non-lethal” aid to the SNC?

Burns: Syria is a distinct case from Yemen and will require its own unique transition and destination. Syrians will determine the shape of that transition and the society that results. The national covenant of the Syrian opposition describes their desire for a political and economic transition that is peaceful, orderly and stable and that preserves and reforms the institutions of the Syrian state. We support that vision — both because it represents the legitimate aspirations of Syrian people and because we believe it will help create a more stable Syria and a more peaceful region. And after more than ten years spent repressing dissent, Bashar al-Assad lacks legitimacy to take forward the political transition process required to implement that vision.

It is urgent that this transition begin immediately. There is a risk of greater extremism taking root in Syria as the violence goes unabated and even escalates in some regions like Homs and Idlib. The government must stop its repression and allow a transition to go forward. The issue is saving people’s lives, promoting democracy and human rights in Syria and ensuring that Syria does not suffer the fate of other societies that have descended into brutal civil wars.

We cannot speak for the Saudi or Qatari governments. As Secretary Clinton said on April 1 in Istanbul, to support civil opposition groups, “the United States is going beyond humanitarian aid and providing additional assistance, including communications equipment that will help activists organize, evade attacks by the regime and connect to the outside world — and we are discussing with our international partners how best to expand this support.”

Slavin: What do you see as the Russian diplomatic role regarding Syria? If their base at Tartous is preserved, can they be convinced to drop Assad?

Burns: Russia’s diplomatic role is important, both as a permanent member of the Security Council and as a country with a longstanding close relationship with Damascus. Secretary Clinton and Foreign Minister Lavrov are in frequent contact to discuss Syria, and Presidents Obama and Medvedev also addressed this key issue during their meeting in Seoul. Obviously we were very disappointed with Russia’s vetoes in the Security Council. Secretary Clinton and Ambassador Rice have been unambiguous on that point. The Secretary has also been absolutely clear in her comments about deliveries of Russian arms to Syria. Russian officials have more recently claimed that they are “no friend” to Assad and have criticized the regime for “making mistakes” and for “reacting incorrectly” to the demonstrations.

Russia supported the March 21 UN Security Council Presidential Statement that endorsed Joint Special Envoy Kofi Annan’s six point plan to support a cessation of violence and the beginning of a political dialogue in Syria. We believe that Russian pressure contributed to Assad’s acceptance of the Annan mission. We would like to see Russia use its influence with Assad to bring an end to the regime’s violence. We have reinforced with the Russians directly what we have said publicly: that Assad will be judged by his deeds, not his words.

On the issue of Tartous, we believe that Russia’s interests will be best served by supporting an inclusive, orderly transition to stable and legitimate governance in Syria.

Slavin: Did President Obama ask, and did PM Netanyahu agree to holding off on a military strike on Iran this year? Will Israel give the US fair warning if it decides to strike Iran?

Burns: President Obama and Prime Minister Netanyahu met on March 5 to discuss regional issues and Israel’s security. President Obama reinforced during his meeting with Prime Minister Netanyahu that the bond between our two countries is unbreakable and that the United States will always have Israel’s back when it comes to Israel’s security. It is profoundly in the interest of the United States, all the countries of the region and the world to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. The president has said he is committed to preventing Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon and will keep all options on the table to achieve that goal.

We still believe there is time for pressure and diplomacy to work, however. We will continue our efforts on the diplomatic front and will continue to tighten pressure when it comes to sanctions. It is incumbent upon Iran to demonstrate, by its actions, that it will address the concerns of the international community and participate in the upcoming P5+1 negotiations in an effort to obtain concrete results. The president understands the potential costs of any military action and is in constant and close consultation with Israeli leaders. The level of coordination and consultation between our militaries and our intelligence agencies is unprecedented. We intend to make sure this close communication, consultation and coordination continues in the difficult months ahead.

Slavin: With Iran talks upcoming April 13-14, how forthcoming are the US and its partners likely to be to convince Iran to take steps that will slow its progress toward a potential nuclear weapon? Could you envision the Europeans not imposing the July oil embargo, for example, if Iran agrees to stop production of 20% enriched uranium and to stop adding new centrifuges to Fordow? Or are you just going to revive a version of the 2009 CBM and offer fuel for the Tehran research reactor?

Burns: The Obama administration believes there is time to pursue a solution to the world’s concerns about Iran’s nuclear program through a combination of diplomacy and strong international pressure. We look forward to the upcoming resumption of P5+1 talks with Iran. It is an opportunity to see whether Iran is prepared to engage in serious negotiations over its nuclear program, in particular whether it is willing to engage concretely on practical steps that can build confidence in its intentions regarding its nuclear program. We want to establish a sustainable process that can produce tangible results. We hope that Iran will come to the negotiating table prepared to get down to business and to reach agreement on early, concrete steps. The opportunity for diplomacy is open; but it is not open-ended. We urge Iran to take advantage of this opportunity. If it does not, it will face ever-increasing pressure and isolation.

Slavin: Egypt now has a parliament dominated by Islamist parties and may soon have a president who is an Islamist. Is it fair to say US-Egypt and Egypt-Israel relations are as bad as they have been in decades? What can the US do to influence politics and governance in Egypt?

Burns: It is fair to say that Egypt has reached a transformative moment in its recent history, and that the last few months have reaffirmed what we knew from the beginning: that transitions are never linear, smooth, or easy. In fact, however, we see this as a moment of opportunity. To this end, we have launched a concerted effort to forge relationships across Egypt’s new political landscape, and so far we are encouraged to find many receptive interlocutors. Those seeking to safeguard regional peace, democracy and human rights will have our support. Through both our longstanding partnerships and the new relationships we are building, we will work to make clear that we want a strong, continuing partnership with a stable, successful, democratic, peaceful Egypt. We will also continue to make clear the importance of upholding universal values, including respect for human rights, rule of law, tolerance, non-violence and protection for women and minorities.

Without doubt, Egypt has faced many challenges this past year. And yet, through a season of revolutionary change, Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel has held and Egypt’s strong security cooperation with the United States has also continued. As we see it, this cooperation is in the profound mutual interest of both our countries. There will be many more challenges and tests in the months ahead for Egypt and US-Egypt relations. But we feel confident that our partnership with Egypt will endure.

Barbara Slavin is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and Washington correspondent for Al-Monitor. This piece was originally published in Al-Monitor.

Image: billburns.jpg