President John F. Kennedy wittily observed that “the only thing worse than being an enemy of the United States was being an ally.” Beyond the humor, JFK was reminding people of the often harsh and unjust treatment America served up to its alleged friends. With the visit of a high-level Pakistani delegation to Washington Wednesday to promote a new strategic framework and relationship, this quip will be put to a test.

We all know the ups and downs and love-hate interactions between the United States and Pakistan — still designated as a major non-NATO American ally — and the significance of trust deficits that need to be closed. Further, the often profound cultural, economic, social and political differences between the two friends and democracies obstruct and can overwhelm good faith efforts to achieve peace, prosperity and stability in a region vital to more than the states located there. The war in Afghanistan of course has complicated the range of choices and options to achieve effective and agreed on policy actions.

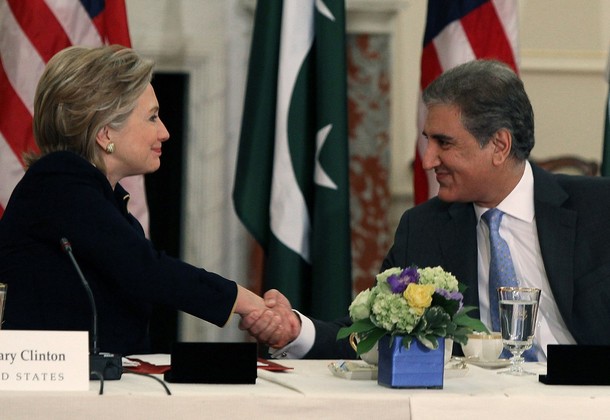

After a series of visits to Pakistan by U.S. Cabinet secretaries Hillary Clinton and Robert Gates, national security adviser James Jones, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Adm. Mike Mullen and Special Envoy Richard Holbrooke, the White House believes it understands the new strategic relationship in which Pakistan is taking a much more aggressive stance in dealing with what its leadership from President Asif Zardari, the Cabinet and National Assembly to army chief Gen. Ashfaq Pervez Kayani agree is an existential threat to the nation in the form of insurgents, terrorists and radical groups conspiring to overthrow the elected government.

But skepticism and cynicism persist and are magnified by the past unhappy history of friends being treated worse than enemies. The political processes and cultures of both friends contribute to continuing this unhappy legacy.

From the U.S. perspective, Pakistan is vital to success in Afghanistan. That means closing the 1,400-mile border or at least going after so-called Afghan Taliban who are killing NATO forces is a crucial step for Pakistan. In return, the United States has promised ample economic and military support as well as a good-faith effort to improve relations with India thereby reducing the tensions that have led to three wars.

From the Pakistan side, its national security strategy is largely synonymous with army thinking. Its forces have been stressed and clearly cannot take on simultaneously all the missions the United States wishes, including the civil side of rebuilding vast stretches of its territory destroyed by the war.

U.S. economic support has been too slow — it may take months for the first tranche of the $1.5 billion Kerry-Lugar money to reach Pakistan and quite frankly and despite Herculean efforts by the U.S. military to provide the sinews of war to Islamabad, the actual deliveries have been embarrassingly small.

Meanwhile, both Zardari and U.S. President Barack Obama face growing opposition at home. The healthcare debate in the United States has been draining despite the apologies and the slap in the face Israel delivered during a visit by U.S. Vice President Joe Biden announcing an additional 1,600 settlements have eroded Obama’s standing. Anti-U.S. sentiment reigns in Pakistan and too much of the media and some of the judiciary seem bent on taking the government down.

Given these realities and the long-standing difficulties between America and Pakistan, how can this meeting close the trust deficit, improve relations and let both states achieve their objectives?

From the Pakistan side there needs to be greater incorporation of what NATO calls the comprehensive or all of governance approach. Military force can clear and hold but it cannot rebuild and provide all the governance as well as strengthening of institutions crucial to keeping a state from failing. For that, Pakistan needs far greater assistance.

The United States must recognize that both sides still don’t agree on all aspects of this new strategic structure. Hence, this meeting must establish where both sides agree, where there is disagreement and how those differences can be addressed.

Finally, the United States must make a dramatic gesture to demonstrate to Pakistani leaders and public that the new relationship is real. Granting relief on textile tariffs (that would come at the expense of China or India whose quota would be reduced not U.S. farmers or workers); encouraging the European Union to do the same; and making a significant transfer of needed arms, helicopters, armored vehicles and other equipment in a timely fashion will help reshape Pakistan attitudes and remove some of the poison. And the United States should at least agree to discuss a nuclear treaty with Pakistan to bring some level of equality with India.

If these steps or ones like them cannot be taken, JFK will be proven right — with tragic consequences.

Harlan Ullman is an Atlantic Council Senior Advisor and chairman of the Killowen Group that advises leaders of government and business. This column was syndicated by UPI. Photo credit: Getty Images.

Image: clinton-querishi-dialogue-photo.jpg