Financial Times columnist Philip Stephens argues we are "On the way to a New Global Balance” in which China, India, Turkey, Indonesia and perhaps others are gaining fast in the race to the top. He contends the long-predicted multipolar world "has rushed quite suddenly into the present" and "Two centuries of western hegemony are coming to a close rather earlier than many had imagined.”

The statement will strike more prudent ears as a fine example of the journalist’s mantra, “simplify and exaggerate.” But Stephens makes a strong point. It’s just not a very original one. Ever since the late Samuel Huntington roused the ghosts of Spengler and Toynbee by throwing down the gauntlet before Western triumphalists with his case for a clash of civilizations, the West vs. the Rest theme has been a media favorite. Popular writers like Fareed Zakaria and Pharag Khanna have done their part to update, recast and refine the argument while resurrecting those of Paul Kennedy so that something of a consensus has emerged, at least in the US: Western power is on the decline as the rising non-Western nations grow richer and stronger, both relative to one another and to the Western nations with which they both collaborate and compete. “Western civilization,” however, is on the defensive.

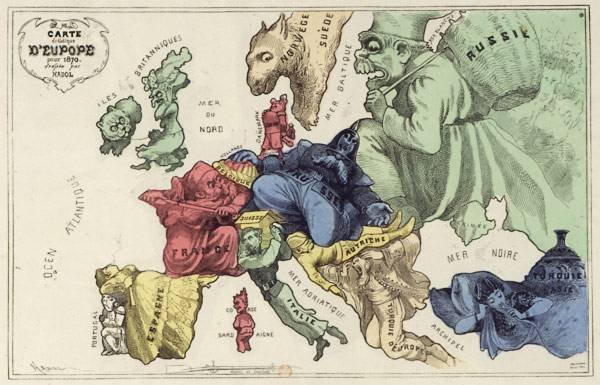

Whatever one makes of this diagnosis, the coexistence and conflation of so many directions for collective pride, ambition and strife—national, regional, global and universal—gives new meaning to the “precarious balance” elaborated by the diplomatic historian Ludwig Dehio so many decades ago. Indeed, the situation may resemble not so much a new medievalism or an Orwellian compartmentalization of superstates as a blurring of regional and global struggles for hegemony of the kind that took place between Germany, the US, and Japan, and the British and Russian empires at the turn of the last century.

Today’s second tier powers may be called revisionists in the traditional sense, and nobody knows how far they will go or what they will do along the way. Nor does their rise necessarily mean an inevitable decline and distintegration of any other power or group of powers: furthering peace and prosperity for the greatest number of them is the first task of diplomacy, not least for the “old” nation-states of the West.

This latter point was the principal theme of Barack Obama’s New York Times essay ("Europe and America: Aligned for the Future") on the eve of his recent trip to Europe. There can be little doubt that he and his administration meant to bolster the transatlantic commitment. In one important way, however, the article does the very opposite, and its vague terminology is symptomatic of the muddle that now threatens to generate the self-fulfilling prophecy of so many West-enders.

The article conflates several terms—relationship, partnership, alignment, alliance—using them more or less interchangeably. This ought to worry more than just diplomatic traditionalists. Terms matter. “Relationships,” “partnerships” and “alignments” are weaker than “alliances” and much weaker than “communities”—a term that does not appear anywhere in the article but that has been used consistently during the past half-century to describe the West and a half-century before that—by Woodrow Wilson— to describe the form of world order that would, with America’s special help, overtake the balance of power that failed so dramatically in 1914. George W. Bush resurrected the latter term and called it a balance of power that favors freedom. And now this has been downgraded, probably inadvertently, to a mere alignment.

“The Atlantic Community” was always a work in progress, to be sure. Its size, shape and essence have long been disputed along a spectrum from partnership to all-out union. From the late 1950s to the late ‘60s, such heated intramural debates took place among Atlanticists, Europeanists, Gaullists and others of an even more obscure nomenclature until Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger put a temporary halt to them by declaring that world order would henceforth begin and end with a condominium among the major powers, viz. the USA, Soviet Union and China, with others playing a supporting role. America’s NATO allies, whom Kissinger told they had merely regional interests in contrast with America’s global priorities, were requited in 1969 with a high profile presidential trip—Nixon’s first in office—and their very own “year of Europe” in 1973.

Those days are long gone, and Obama is right to suggest that both Europe and America have global responsibilities. But whether they work in tandem or as members of a single, organic and open community that is, to use Obama’s words, a “cornerstone” and a “pillar,” is not preordained by superior historical forces. As Americans like to say, decline is a choice. And a one-time community that chooses to see itself as little more than a dual track separated by a large ocean is bound to erode and dissolve sooner or later.

Kenneth Weisbrode is a historian at the European University Institute and author of "The Atlantic Century."

Image: balance%20of%20power2.jpg