The United Nations Security Council has endorsed US President Donald Trump’s twenty-point plan for Gaza, with a resolution that authorizes a transitional authority and an International Stabilization Force (ISF) to ensure security and support demilitarization efforts in Gaza. Hamas rejected the UNSC resolution and ISF, and the group shows no willingness to give up its weapons or to yield its role in governing Gaza.

While the question of whether the ISF would get a mandate is no longer the blocker, ISF composition and troop contributions remain unsettled, and Israel has sought to veto the participation of several countries, most notably Turkey. Turkey seems ready to participate, but it is uncertain whether the United States will put pressure on Israel to bring Turkish forces into the ISF or whether Washington will find another role for Turkey in implementing the peace plan.

The Middle East Eye reported that Turkey is drafting a brigade—roughly two thousand personnel, including land forces but also specialists on engineering, logistics, and explosive ordnance disposal—for potential participation in the Gaza stabilization mission. Ankara has also set its own condition: that the creation of the ISF must guarantee a lasting cease-fire.

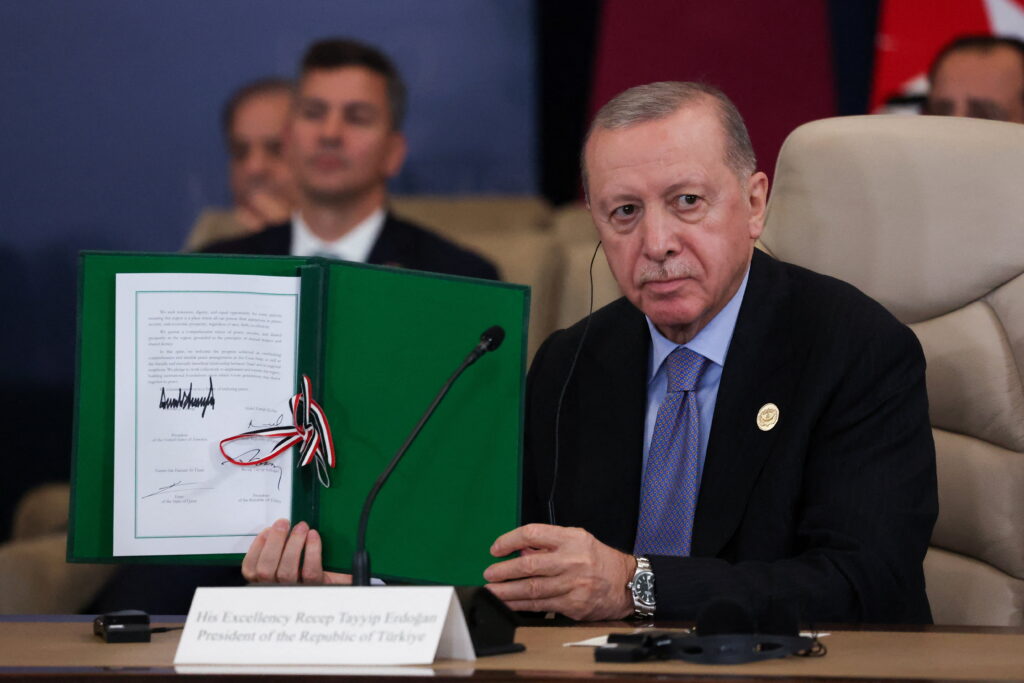

Turkey’s readiness to participate, Israel’s rejection of Turkey’s role, and conditions that both countries have placed on the ISF mission reflect a deeper divide. Turkey has been a constant critic of Israel, ramping up its condemnations during the war in Gaza. For its part, Israel points to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s close relations with the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas. Excluding Turkey would be problematic, however, as Ankara is among the guarantors of the cease-fire plan and Erdoğan had a prominent role in the Sharm el-Sheikh Peace Summit in October.

The question, then, isn’t simply whether Turkey becomes part of the ISF; it’s where Ankara can—or cannot—add value without breaking the fragile political math.

Israel’s objection comes down to politics, not capabilities

Turkey has substantial peacekeeping credentials (including maritime and Balkans missions). Its reported preparations for a Gaza brigade underscore its capacity. But Israel, in demanding “no Turkish boots on the ground,” is more focused on its distrust of Ankara’s ties with Hamas and Turkey’s past hostile relations with Israel.

Turkey is seen by many countries as a credible security actor in the region, but its policies are not without critics and opponents. Egypt’s relations with Turkey, for example, pass through periods of strain, and thus Egypt will likely insist on having a say in what kind of role will be assigned to Turkish troops. The United Arab Emirates might also raise questions about Turkish involvement—although, perhaps not, seeing as it appears to have ruled out a troop commitment role for itself and thus may not have a strong preference about Turkey’s role. Thus, it’s a toss-up whether excluding Turkey would impact regional buy-in for whatever force emerges.

The immediate needs in Gaza are engineering-heavy: the clearance of unexploded ordnance, the removal of debris, power and water restoration, bridging, and the improvement of medevac services. Those are areas where Turkish units have proven experience, but the Egyptian military has as well. Turkey can make a case for participation owing to its military’s competencies, but that will not necessarily assure its role.

Perhaps Turkey’s most important political asset in this discussion is its ties to Hamas, which helped bring about the cease-fire and which could prove instrumental in ensuring the cease-fire holds, as well as moving toward Hamas disarmament. For example, recent reporting indicated Turkey was involved in sensitive talks over holdout Hamas fighters in tunnels—precisely the kind of quiet Turkish action that can reduce violence.

Where Turkey fits in

The US-led Civil-Military Coordination Center (CMCC), established in southern Israel in October, has become the coordination spine for “day-after” mechanics—aid flows, deconfliction, and scaffolding for any future ISF. Multiple accounts over the past month report that the CMCC is increasingly shaping logistics and compliance under the cease-fire plan. Ankara understands this and appears ready to fit in seamlessly with the operation, which is headed by US Central Command. This points to a realistic possibility for Ankara’s involvement in which Turkey is adjacent to (rather than inside) the ISF’s core formation; and it could allay some of Israel’s concerns. Turkey’s work, alongside the CMCC and otherwise, could include the following:

- Off-shore training and vetting of Palestinian police. Turkish (and Jordanian) facilities could host accelerated cycles for a reconstituted, internationally vetted police service—politically tolerable to Israel and operationally essential for Gaza. Coordination would run through CMCC and relevant UN channels. This would be feasible even if Turkish infantry never sets foot in Gaza.

- Engineering, explosive ordnance disposal, and medevac under UN umbrellas. Technical detachments working under UN humanitarian cluster systems—rather than frontline “peacekeeper” formations—could address the most life-saving tasks with the least political friction. The reported emphasis on engineering/explosive ordnance disposal in Turkish planning aligns with this.

- Quiet diplomacy on sensitive files, such as tunnels/holdouts, remains recovery, or border deconfliction. This is where Ankara’s channels can move needles without personnel on Gaza’s streets.

While the resolution authorizes an ISF and envisages demilitarization support and civilian protection, it leaves rules of engagement and the precise disarmament mechanics to follow-on arrangements under the transitional bodies. Reporting also indicates that Turkey and Egypt prefer a mandate that prioritizes border control, de-escalation, and reconstruction over coercive disarmament during a fragile truce. Given that, the most probable outcome for Ankara’s involvement remains not hosting Turkish infantry in Gaza, but allowing Turkish assets that plug into CMCC-coordinated humanitarian and policing pipelines.

In view of Trump’s warm relations with Erdoğan, it is likely that the US administration will try to find a way to overcome Israeli objections and to assign a role for Turkey in the ISF. Even if Turkish soldiers don’t patrol Gaza’s streets, Ankara can play a role, which it clearly desires to do, that helps shape policy and rebuild Gaza. Thus, Turkey and Israel should spend their time not issuing demands to each other but instead working with the United States in developing a role for Ankara that helps advance the ISF mission.

Daniel C. Kurtzer is a former US ambassador to Egypt and former US ambassador to Israel, as well as the S. Daniel Abraham professor of Middle East policy studies at Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs.

Kayra Sener is a program assistant of the Atlantic Council’s Realign For Palestine project.

Further reading

Wed, Oct 15, 2025

Twenty questions (and expert answers) about the next phase of an Israel-Hamas deal

New Atlanticist By

What will follow part one of the cease-fire deal brokered by the Trump administration? Atlantic Council experts share their answers.

Tue, Nov 18, 2025

How Trump can leverage the Saudi crown prince’s visit to help secure Gaza’s future

New Atlanticist By Melanie Robbins

Trump should work with Saudi Arabia and the UAE on a Gaza stabilization fund and a more cohesive plan for implementation.

Mon, Nov 10, 2025

A little-discussed point in Trump’s Gaza plan could be an opportunity to build interfaith understanding

MENASource By Peter Mandaville

Peace efforts don’t need more gleaming Abrahamic baubles, they need a genuine commitment to supporting grassroots religious peacebuilding.

Image: Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan poses with the signed agreement at a world leaders' summit on ending the Gaza war, amid a U.S.-brokered prisoner-hostage swap and ceasefire deal between Israel and Hamas, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, October 13, 2025. REUTERS/Suzanne Plunkett/Pool