While there has been much debate about who bears the cost of US tariffs, it is US importers of Chinese goods, and not China, that have to pay. Many of these tariffs significantly increase the price of intermediate goods, such as auto parts and computer components, needed by US manufacturers to produce competitive products in the United States. The additional cost of higher tariffs also forces large numbers of US consumers to pay.

An analysis released by economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Princeton University, and Columbia University in March asserted that Americans were paying “the full incidence of the tariff.” And a more recent Goldman Sachs Research report cited two academic studies showing that “Chinese exporters did not absorb any of the tariffs in their profit margins.”

If these patterns remain the same in the future, and current US tariffs are raised, as planned, from the current 10 percent to 25 percent on $200-billion worth of Chinese goods, that would be equivalent to a tax increase on Americans of $20 billion. If 3,800 new items, worth about $300 billion, are added to the tariff list, US businesses and consumers will pay roughly $75 billion more, according to some economists.

Tariffs are, we should remember, a tax paid by Americans on imported goods. Moreover, import-competing US domestic producers generally raise the prices of goods they sell to levels equivalent to the higher prices charged for the imported goods subject to higher tariffs.

A Chinese supplier may decide to reduce its price to the American importer in order to offset part of the higher tariff and thus to remain competitive in the US market. It is a question of what the market will bear. Each company will have to decide. If US tariffs are raised to levels now planned, that issue will become a bigger dilemma for Chinese companies.

Many Chinese companies, of course, will look to other overseas markets to reduce dependence on the United States and thus soften the impact of any profit losses or volume declines. But for numerous Chinese businesses a full or even a partial offset might not be possible.

The Trump administration sees higher tariffs as leverage, and to a substantial degree they are. But history demonstrates that leverage is not unlimited or always efficacious. There are, for example, limits to how far China will go in meeting US demands as tariffs escalate, especially if its leaders see their country’s core interests being threatened by those demands, or if a nationalistic backlash imposes constraints on their responding to those demands. That may well be the current situation—although we shall see more clearly as the G-20 meeting in Japan at the end of June approaches and after that meeting itself.

In current circumstances, it is not only the escalation of tariffs that is controversial, but exactly how the tariffs are used as leverage. For example, reports that the United States wants to retain at least some of its tariffs on Chinese goods after a deal is reached in order to ensure Chinese compliance is reportedly seen by leaders in Beijing as an unacceptable. So too is Washington’s insistence that in the future the United States could reimpose tariffs if it decided that China was violating the agreement, while China would be asked to commit not to retaliate. Chinese officials have characterized these as “unreasonably high demands” that are “intervening with Chinese sovereignty.”

Moreover, tariff escalation imposes substantial costs on US companies and consumers; the longer the tariffs last, the higher they rise, and the greater the volume and categories of items covered, the greater the costs. More broadly, they will slow US growth and boost domestic costs.

Some US companies clearly benefit from higher tariffs. A number of businesses in tariff-protected industries are reaping higher profits. Hiring and wages are growing in these industries as well. But most US consumers are paying, or will pay, higher prices due to escalating tariffs and higher prices charged by domestic producers of comparable goods. For many US industries that import Chinese components for incorporation in final products made in the United States, and thus bear the burden of higher tariffs, and the many retailers that sell Chinese-made products, profits as well as wages paid to their workers and jobs are likely to decline. In addition, significant parts of the economy have been subject to retaliatory measures by China, with more likely to come; this notably includes farmers, but extends to numerous other sectors as well.

Also, the process of negotiating a reversal of the tariff war becomes more difficult if each side believes it can force the other into making concessions by raising tariffs on its products. And now, both Washington and Beijing appear to have concluded that tariff increases are not sufficient to achieve their negotiating goals; they are escalating deployment of non-tariff measure against one another, including restrictions on investment as well as on exports of core technologies and other critical items. Curbs on purchases of advanced technology products, primarily in the area of telecommunications, have been imposed as well.

Robert Hormats is an Atlantic Council board member, vice chairman of Kissinger Associates Inc., and a former US undersecretary of state for economic, energy and environmental affairs.

This is part of a series of blog posts on the US-China trade relationship in the runup to the meeting between US President Donald J. Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping later this month at the G-20 Summit in Japan.

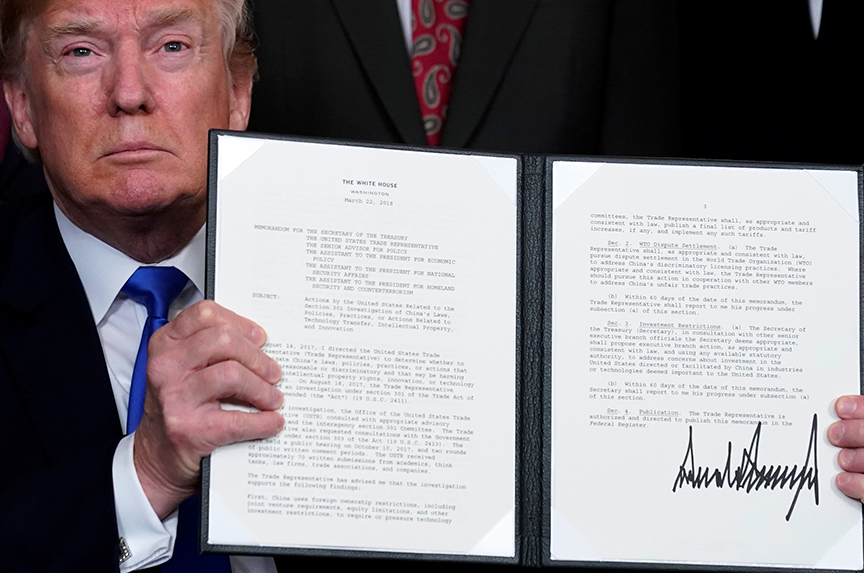

Image: US President Donald J. Trump held a signed memorandum on intellectual property tariffs on high-tech goods from China at the White House in Washington on March 22, 2018. (Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)