Wired‘s Spencer Ackerman reports on the Pentagon’s measures to fix obvious flaws in its security revealed by the Wikileaks debacle.

Tomorrow’s WikiLeakers may have to be sneakier than just dumping military docs onto a Lady Gaga disc. The futurists at Darpa are working on a project that would make it harder for troops to funnel classified material to WikiLeaks — or to foreign governments. And that means if you work for the military, get ready to have your web, email and other network usage monitored even more than it is now.

Darpa’s new project is called CINDER, for Cyber Insider Threat. It’s lead by a legendary hacker-turned-Darpa-manager. CINDER may have preceded Pfc. Bradley Mannings’ alleged disclosure of tens of thousands of documents about the Afghanistan war from Defense Department servers. But the idea is to find someone just like him. By hunting for poker-like “tells” in people’s use of Defense Department computer networks, Darpa hopes to find indications of indicate hostile intent or potential removal of sensitive data. “The goal of CINDER will be to greatly increase the accuracy, rate and speed with which insider threats are detected and impede the ability of adversaries to operate undetected within government and military interest networks,” according to the defense geeks’ request for contractor solicitations on the project.

[…]

“We want those soldiers in a forward operating base to have all the information they possibly can have that impacts on their own security, but also being able to accomplish their mission,” Gates mused in a July press conference. “Should we change the way we approach that, or do we continue to take the risk” of future leaks? Gates partially answered his own question — however cryptically — by adding, “There are some technological solutions,” though “most of them are not immediately available to us.”

That’s where CINDER comes in. But the program Darpa envisions would establish patterns of malign behavior, distinct and quietly detectable from the normal Defense Department information user, to “expose hidden operations within networks and systems.” That carries with it the likelihood of a big data or meta-data-mining operation. Or, as Steve Aftergood, an intelligence-policy expert at the Federation of American Scientists puts it, “a sort of system-wide surveillance of Pentagon networks.” After all, how else to tell normal network usage from abnormal usage?

Indeed, Darpa expressly recognizes CINDER’s likelihood of intercepting false positives. So Darpa doesn’t want CINDER from focusing on any individual user — it wants the program’s as-yet-unbuilt algorithms to uncover the “malicious missions” that they undertake. “If we were looking for the insider actor himself, we might not detect someone who performs a single, isolated task and we run the risk of being inundated with false positives from events being triggered without context of a mission,” Darpa explains. It gives instructions for would-be designers to expressly identify the kinds of missions its detectors will hunt so as to minimize inundation with a glut of benign data.

This is one of those innovations that, in hindsight, seem obvious. Indeed, my immediate reaction when first learning of this via Twitter was shock that they weren’t already doing this. But, of course, increased security has costs in both manpower and trust, both of which are acceptable only after a high level breech has occurred.

Alas, Ackerman reports that, "A full-blown CINDER application is still years away. " Presumably, though, intermediate measures are already in place to make the theft of tens of thousands of documents more daunting.

While these measures will produce more cost for the taxpayer and an even less comfortable workplace for those who toil in the national security business, they’re far preferable to what I presumed would be the natural bureaucratic action here: a return to massive stovepiping of information. Our enemies don’t have to steal our secrets, after all, if they’re safeguarded from people who have a legitimate need to know but can’t get it for fear that it’ll show up on some anarchist’s website.

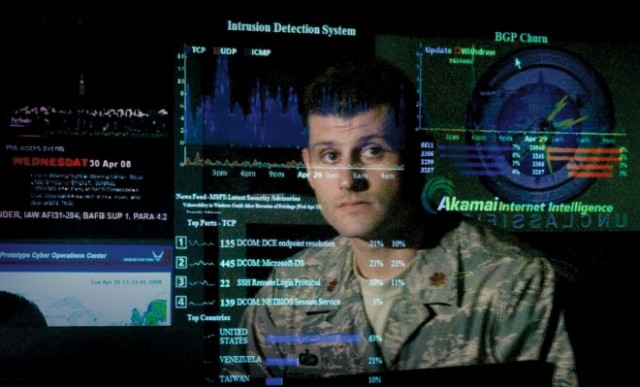

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council. USAF Photo.