Ukraine’s presidential campaign season has unofficially begun. Almost half a year before the presidential race in March 2019, candidates have already settled on basic strategies.

Ukraine’s presidential campaign season has unofficially begun. Almost half a year before the presidential race in March 2019, candidates have already settled on basic strategies.

Let’s analyze their messages—how they separate themselves from their competitors and try to create an attractive image, what ideas “sell,” how they struggle with criticism, negativity, compromise, and ultimately, how they plan to win the elections.

Yulia Tymoshenko uses a “panacea effect”

To offer easy solutions to difficult problems is a typical tool for populists. Fatherland candidate Yulia Tymoshenko’s new advertising campaign, “New Course of Ukraine,” tries to persuade voters that a new constitution will solve every problem.

Here’s how she “sells” it: “I am constantly questioning why nobody in our country is not responsible in any way, why there is no justice in the courts, why we have high tariffs and such humiliating poverty, why we have corruption, why we have such a mess. And the answer is very simple. This is an old corrupt system, enshrined in our current constitution… We will work out a new people’s constitution together with you… The new constitution will establish fair rules of our life, it will return Ukraine to people and will enable everyone to live successfully.”

Recognizing some imperfection in the constitution (although it has been called one of the best in Europe), the key issue is that basic laws are not observed. Even if a new constitution is adopted but not observed, how will it solve these problems?

Yuriy Boyko pushes peace

Opposition Bloc candidate Yuriy Boyko is pushing for peace. On July 27, he prayed for peace during the procession of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, declaring that the Opposition Bloc wants peace and claims to have a concrete plan for resolving the conflict in the East.

Here he tries to trap voters. How can anyone vote against peace? Everybody is tired of the war. And voters are pushed to vote not for a specific surname, but for achieving a long-awaited peace.

Of course, there’s a problem with this slogan. The end of the war does not depend on any Ukrainian politician; only Vladimir Putin can force the Russian armed forces to lay down arms. And Putin will do it exclusively on his terms.

Boyko is not the only candidate who exploits “peace.” All pro-Russian politicians do. For the sake of Boyko’s electoral prospects, he needs to become the only pro-Russian candidate with a unique “peace” proposal.

Petro Poroshenko uses a “virtual competitor” strategy

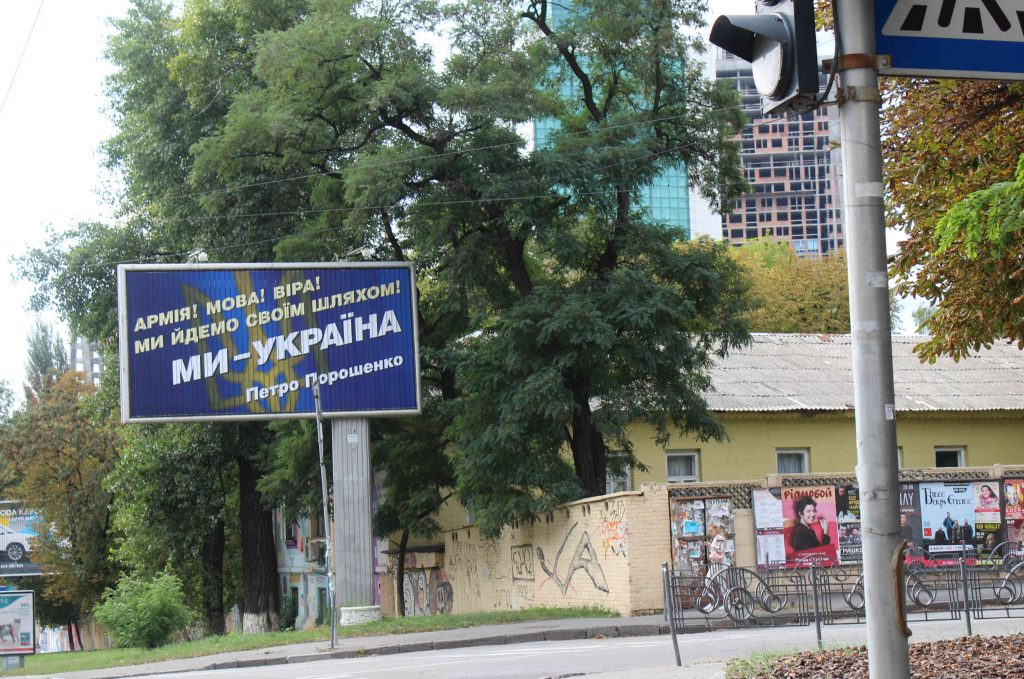

The current president launched a campaign with television ads and billboards that proclaim, “Army! Language! Faith! We are Ukraine.” At the same time, Poroshenko ignores his competitors.

It’s also worth mentioning that Viktor Medvedchuk, often called Vladimir Putin’s man in Kyiv, has gotten stronger. He began to buy television channels and is attempting to capture the Agrarian Party. Medvedchuk serves an effective boogeyman for Poroshenko. Medvedchuk’s growing position should be understood as an attempt to implicitly push Ukrainians to unite around a single pro-Ukrainian president, so they conclude that Poroshenko as the only decent supreme commander of the Ukrainian Armed Forces is the obvious choice.

Anatoliy Hrytsenko tries to unify opposition

The most important trend in this election campaign is the demand for new faces, and the old faces are disliked. Even though Hrytsenko is not a new face, he’s perceived as one.

Hrytsenko is focused on unifying many small reform parties. In the spring, Yegor Firsov’s Alternative and Dmytro Dobrodomov’s People’s Control united in a single platform with Hrytsenko’s Civil Position.

It is likely that other political newcomers, including Victor Chumak’s Wave civil movement and Mykola Katerynchuk’s European party will join this alliance.

Most importantly, Hrytsenko needs Lviv Mayor and head of the Samopomich party Andriy Sadovyi to join forces. Earlier this year, billboards with a picture of Sadovyi and Hrytsenko were placed in Kyiv with the slogan “Unite for the sake of Ukraine.” Hrytsenko’s representatives were mostly likely behind them. However, Sadovyi is in no hurry to support Hrytsenko. This is understandable, since Samopomich will likely nominate its own presidential candidate.

In general, unifying behind one candidate isn’t enough to ensure the success of Hrytsenko. He lacks financial resources, an organizational structure at the local level, and access to television.

Oleh Lyashko sounds like a Ukrainian version of Donald Trump

Radical Party chairman Oleh Lyashko projects the image of a simple village man with a pitchfork who sincerely engages in “truth-telling” and wants to take on the oligarchs.

Lyashko’s election campaign will draw on the same protectionism and isolationism that worked for US President Donald Trump. Rather than America First, Lyashko will run on a Ukraine First strategy.

Last year he promoted the slogan “Buy Ukrainian, pay Ukrainians!” and a bill with a similar name. The bill complicates the online procurement system Prozorro and does not provide support for all Ukrainian producers, only for big business and oligarchs.

Quick makeovers

This is a classic game. All candidates try to patch up vulnerabilities before elections, and Ukraine’s candidates are no exception.

Lyashko decided to formally marry this summer after twenty years of civil marriage. In principle, he could have continued to live in a civil marriage, but legally marrying will help bolster his claims of being a family man.

Poroshenko promised to finish the war in a week, which leaves him vulnerable. On the eve of Ukraine’s Independence Day, he apologized. By admitting his own unfulfilled promise, he mitigated any future attacks from his opponents. The president’s action was also sudden and unexpected; in Ukrainian politics, there is no tradition of apologies.

Tymoshenko faces charges and rumors that she is a “Kremlin stooge.” So she urged politicians to sign a memorandum on the unchanging course of European and Euro-Atlantic integration. The memorandum is not binding, it has no legal force, but ostensibly it refutes Tymoshenko’s loyalty to the Kremlin.

Attacks and attempts to establish a link between Tymoshenko and Russia will continue. Ivan Melnychuk, an MP from the Poroshenko Bloc, recently promised to provide evidence of Tymoshenko’s son-in-law visiting Moscow. But these attacks might backfire. Accusing Tymoshenko of being pro-Russian may increase her attractiveness to a huge part of the pro-Russian electorate, who are disappointed with the former Party of Regions and will not vote for Boyko.

The presidential election will play a crucial role in shaping Ukraine’s future. There are two different options. First, if a pro-Ukrainian candidate wins, there’s a high probability that Ukraine will still be an independent country with ambitions to join the European Union and NATO, defending against Vladimir Putin’s military aggression in the east.

The second option, the victory of a pro-Russian candidate, means a surrender to Putin and the end of Ukraine as we know it. That’s why one of the most challenging tasks is to resist Russia’s powerful interference as it bets on several candidates and tries to discredit the current government.

Olexiy Minakov is a political expert in Kyiv, Ukraine and a columnist for RFE/RL. This commentary first appeared on Ukrainian at RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service website and has been translated and edited with the author’s permission.

Image: A billboard for President Petro Poroshenko says "Army! Language! Faith! We Are Ukraine" in downtown Kyiv, September 16, 2018. Credit: Melinda Haring