Russian-Sponsored Rebels Hold a ‘Referendum’ on Separation from Ukraine, But a Local Journalist Finds It a Farce

Donetsk resident Ihnat Svyachyshyn sets off to vote in the May 11 Donetsk separatist referendum. He asks his neighbors, a couple in their mid-twenties to join him but they refuse. While they support a federalization of political power in Ukraine, they think the referendum is being held improperly.

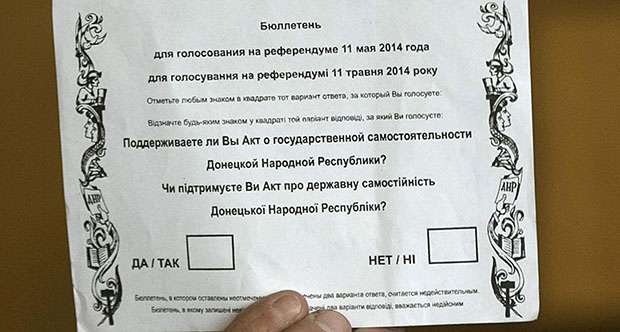

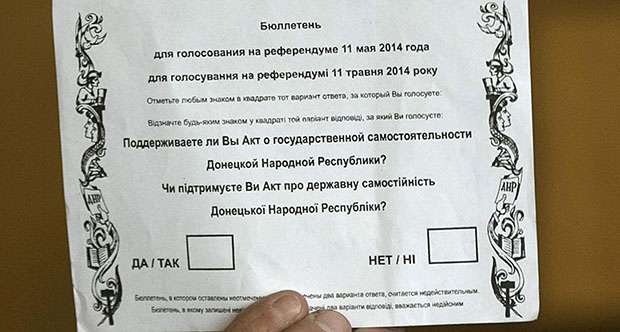

Svyachyshyn, a writer for the Donetsk-based news website Novosti Donbassa, starts early in the morning as he heads to vote at School No. 60, in the city’s Smolyanka neighborhood. Few people are present and he is glad to note that there are no armed, masked men. He shows his passport and is given a ballot. His request to also vote for his wife (he actually has no wife) is rejected because he can’t present her passport. An elderly woman standing behind him votes for her entire family, having come with all their passports.

|

Svyachyshyn marks his referendum ballot with a ‘no’ vote and drops it in a clear ballot box, which he notes is already about 20 percent full. It is 9 a.m.

His next stop is the House of Culture in Panfilov Street, a busier polling station in the same neighborhood. This time, a poll worker hands Svyachyshyn a second ballot to vote for “wife,” asking only for her name and date of birth. Syvachyshyn votes no again and pockets the extra ballot.

Next is School No. 17 on Oreshkova Lane in central Donetsk, very near the provincial government headquarters building, which is controlled by the militant separatists. Russian journalists mill outside, while inside is a perfect picture for official Russian television: long lines of eager voters. Again he gets two ballots, votes ‘no’ and pockets his fictional wife’s ballot. Although this polling station is filled with people, he notes that the ballot box is not nearly as full as the one where he first voted.

Our determined voter proceeds to another school, which he doesn’t name because, he says, it is close to the office of Novosti Donbassa, which these days must operate clandestinely following threats and attacks that forced its publisher to leave town. Here, he is asked to write a request to be added to a list of voters. His “wife” is not able to vote here.

About 12:30, Syvachyshyn returns to the last polling station to find it practically empty. The number of ballots in the box hasn’t grown noticeably since he was here two hours earlier.

Svyachyshyn now has two empty ballots which he can freely copy in any copy center in Donetsk, he writes. “I can make 1,000 or 10,000 copies and open my own polling station, just like they did right on the streets in [the cities of] Mariupol and Krasnoarmeysk,” he writes. “Come and vote,” he says, “I won’t even ask for your passport.”

Imprisoned in Slaviansk: A Journalist’s Story

From the prison of Slaviansk, the center of violence in the uprising, journalist Serhiy Lefter emerges to speak of his detention. No one really knows how many people have been taken captive by the armed separatists. The vast majority of people kidnapped or detained by the masked gunmen have gone missing in Slaviansk, in the north of Donetsk province. Lefter was one of several journalists detained in April. He was released May 2 after nearly three weeks in captivity, and described his detention during a press conference in Kyiv.

Lefter’s captors accused him of being a spy and “a Pole” (most likely, he says, because he writes for a Polish pro-democracy foundation, “Open Dialogue”) and a member of the Ukrainian right-wing nationalist group “Right Sector.” His release, says Lefter, was surprising and rather arbitrary. “A person simply walked in and sorted us into two groups, one group was set free, the other group remained in captivity.”

Those captured were held in three rooms of the local government headquarters building, sometimes with as many as 16 people to a rooom. The militants were constantly bringing people in or taking them out throughout the days and nights.

The first week was the hardest, says Lefter. His hands were always tied and his eyes were taped over. Usually around midnight, he would be taken for interrogation. With his eyes always covered, he learned to identify his captors by their voices. In each interrogation, his captors beat him, Lefter said, sitting before journalists with bruises still visible under his eyes. But his abuse “was a stroking compared to what other people got,” he said. The detainees hesitated to talk even to each other about the abuses, not knowing who could be trusted. Lefter regularly heard the sounds of cruel beatings and the cries of the victims in what he described as an atmosphere of endless menace. “Even when they took us outside to go to the toilet they would jab us with their gun barrels and call us fascists” he said.

Lefter doesn’t know his questioners. When his blindfolds were finally removed, he found that many of his captors were wearing facemasks. “They latch on to every word during interrogation,” said Lefter. “They found my Facebook page and learned that I was on the Maidan” during the pro-democracy demonstrations in the capital, Kyiv.

Slaviansk’s militants are happy to have reporters from Russian television channels, such as the state-run Rossiya 24, tell their story. “Sometimes they even give them an escort so no one bothers them. Russian journalists have access to everything, although the militants don’t allow them into the basement where people are held.”

Irena Chalupa covers Ukraine and Eastern Europe for the Atlantic Council.

Image: Vyacheslav Ponomaryov, separatist "people's mayor" of Slaviansk, holds a referendum ballot during a news conference in Slaviansk, eastern Ukraine May 10, 2014. (REUTERS/Baz Ratner)