Ukraine’s current economic crisis was years in the making. Former President Viktor Yanukovych grossly mismanaged and looted the country. And it may take years for the country to fully recover. But there are signs that the economy has reached the lowest point and its prospects are brighter than commonly portrayed in the press.

Ukraine’s current economic crisis was years in the making. Former President Viktor Yanukovych grossly mismanaged and looted the country. And it may take years for the country to fully recover. But there are signs that the economy has reached the lowest point and its prospects are brighter than commonly portrayed in the press.

First, the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) massive, front-loaded aid package gave much-needed breathing space to the Ukrainian government. The IMF deal gave the government resources to cover the deficit and foreign reserves to defend the hryvnia. Most visibly, the hryvnia appreciated by a third relative to the levels it reached in the heat of the panic in February 2015.

Second, the country’s fiscal position has tangibly improved. While Naftogaz, the state-owned gas monopoly, continues to be a black hole in public finances, the central and local governments had a fiscal surplus in the first quarter of 2015. The government also tripled the price of gas, putting it closer to market levels, thus closing a source of major fiscal problems. Consumers did not complain about the spike in gas prices as much as many had expected. The public perceived that the previous subsidy was not sustainable, and it was widely understood that everyone has to make sacrifices during wartime. In addition, the government provided a transparent and targeted subsidy to the least-protected households, which lessened criticism.

Third, inflation spiked in recent months reaching 60 percent at the estimated rate of annual return. While high, the spike is mostly due to the depreciation of hryvnia in 2014-2015 and a large increase in gas tariffs. Furthermore, a careful analysis suggests that actual inflation may be lower because of biases in the way inflation is calculated by the government. In any case, the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) has implemented a tight monetary policy and projects inflation to subside by the end of the year. Valeriya Gontareva, the head of the NBU, has reiterated the central bank’s commitment to achieving stable and low inflation.

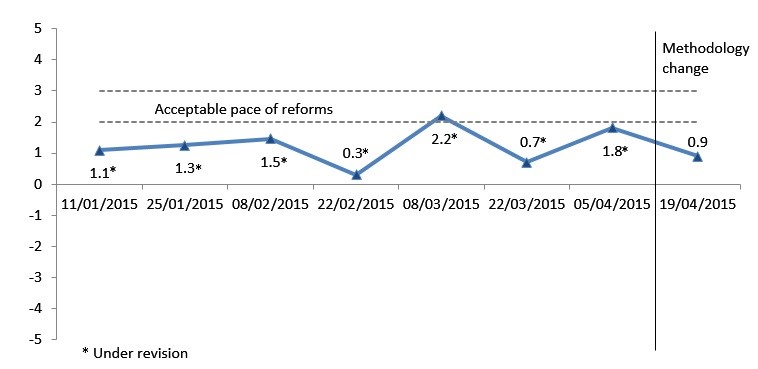

Fourth, the pace of reforms has accelerated in 2015. The government passed and implemented a number of crucial laws to change the institutional environment of the economy. It opened the energy market to more competition, enhanced protection for minority shareholders, cut red tape and regulation, and increased access to public records. Index for Monitoring Reforms, a survey-based index that tracks regulatory changes and is calculated bimonthly based on an expert survey, suggests that the government is serious about reform (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Speed of reforms

Source: IMoRe index.

The government and the IMF expect Ukraine’s economy to recover in the second half of 2015. Obviously, such a forecast is subject to many caveats and risks—most importantly, the recovery depends on reduced tension in the Donbas. There are others signs that things may be turning around: the deeply depreciated hryvnia makes Ukrainian goods competitive; the current account deficit—that is, how much imports exceed exports—fell from $630 million in March 2014 to $13 million in March 2015. The initial shock from increased energy prices and economic collapse in eastern Ukraine is wearing out. And government spending on the military has had a stimulatory effect on the economy.

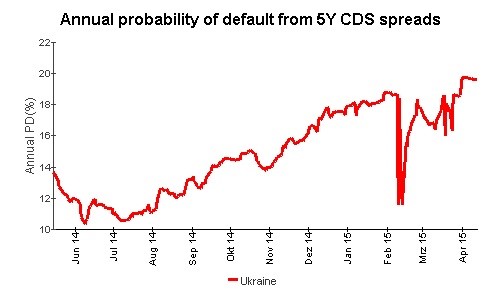

But significant challenges lie ahead. Restructuring the government’s sovereign debt won’t be easy. The IMF package requires the government to reach a deal with its creditors so that the country can reduce its outstanding debt, increase its maturity, and reduce the interest rate. Ukraine doesn’t have much time; the deadline is the end of May. So far the government is not satisfied with the negotiations with its creditors. In 2014 and early 2015, the Ukrainian government could not credibly threaten to default because it did not have the resources to cover a fiscal deficit, but now with a fiscal surplus, the government’s position is considerably stronger. Indeed, the market perceives that some restructuring is imminent: Figure 2 shows that the private market assigns a 20 percent probability of default on Ukraine’s public debt. One may interpret this probability as suggesting that creditors are expected to lose 20 percent in the process of writing down debt. This haircut is in line with the rates observed in previous cases of sovereign debt defaults. Negotiations may be thorny, but the likelihood of a deal is high. State-owned companies have already started to default and restructure their debts thus paving the way for a larger restructuring.

Figure 2. Probability of default implied by credit default spreads on Ukraine’s public debt.

Source: Deutsche Bank

In summary, an economic recovery in Ukraine may be just around the corner. Of course, there is a great deal of uncertainty and the war in the Donbas weighs heavily on the future of the country and its finances. But some economic growth in Ukraine is entirely possible this year.

Yuriy Gorodnichenko is an Associate Professor of economics at the University of California at Berkeley.

Image: Ukraine's Finance Minister Natalia Jaresko and Prime Minister Arseny Yatseniuk address the media during a news briefing in Kyiv on March 11, 2015. The International Monetary Fund's board signed off on a $17.5 billion four-year aid program for Ukraine. REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko