In July, residents of Slovyansk and Kramatorsk marked the first anniversary of liberation from the occupation of Russian-backed separatists. Both cities experienced their rule for nearly four months in 2014. In the last year, marches, concerts, and city lights with slogans promoting peace have helped reinforce a growing sense of national pride. And yet a strong feeling of distrust toward the central government in Kyiv persists. The government has been slow in dealing with the aftershocks of war while assistance to internally displaced persons remains a steep challenge.

In July, residents of Slovyansk and Kramatorsk marked the first anniversary of liberation from the occupation of Russian-backed separatists. Both cities experienced their rule for nearly four months in 2014. In the last year, marches, concerts, and city lights with slogans promoting peace have helped reinforce a growing sense of national pride. And yet a strong feeling of distrust toward the central government in Kyiv persists. The government has been slow in dealing with the aftershocks of war while assistance to internally displaced persons remains a steep challenge.

Hundreds of volunteers from around the country have tried to fill the communications and humanitarian gap in the Donbas. Over the last year, I have been privileged to work in eastern Ukraine as part of the Lviv Education Foundation‘s efforts. I found eight initiatives that demonstrate that volunteerism is on the rise in the Donbas and they—along with the people that I’ve met—give me cause to be hopeful for eastern Ukraine.

1) Fostering Reconciliation Through Rebuilding Homes

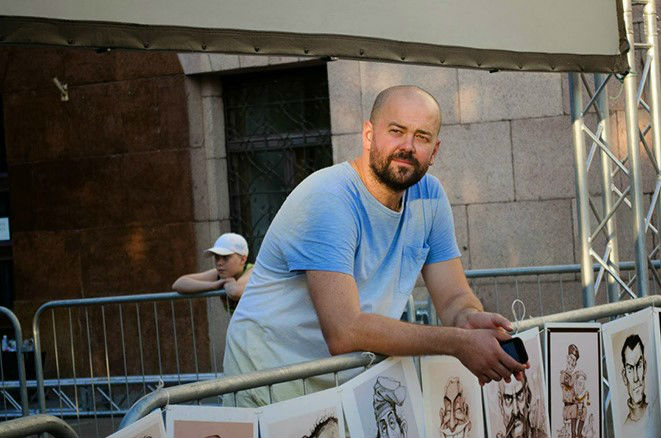

A few weeks after Ukrainian soldiers retook Kramatorsk, LEF set up a volunteer camp made up of more than 80 volunteers from western and central Ukraine who helped locals rebuild homes and social capital in a hard-scrabble city. Thousands of hryvnias were raised through a crowd-sourcing platform and more than thirty houses and apartments were renovated free of charge.

Volunteers fixing a roof in Kramatorsk, August 2014

The camp was unique: in the morning, volunteers performed hard physical labor, while in the evening, they’d gather at a bonfire and chat with locals, which chipped away at the pernicious stereotypes that exist between Ukrainians in the east and west. “We’re not talking about reconciliation and consolidation between east and west. We are carrying it out through joint work for our people who are in need,” said LEF Executive Director Vitaliy Kokor.

2) Giving Civil Society Some Space in Kramatorsk

The Vilna Khata “Freedom Home” youth platform in Kramatorsk grew out of LEF’s efforts in Kramatorsk. Volunteers there rented a house with a garden in the suburbs and invited young people to join them for bonfires, movie screenings, and evening discussions. Before the volunteers came to town, the most intellectual place was a pizza store. Kramatorsk, a city of 200,000 people with four large factories, lacked a single cultural center where young people can gather. After the volunteers left, locals asked them to help create a permanent youth center. Freedom Home has just celebrated six months in operation. Since its opening, more than five thousand people have visited the center—an informal place where eastern Ukraine meets western Ukraine. Anyone can read, have a cup of coffee, play the guitar or enjoy a board game.

Opening Ceremony of Teplytsia Platform for Initiatives in Slovyansk, May 26, 2015

3) Nuturing Democratic Ideas and Civic Activism in Slovyansk

In May 2015, the Teplytsia (“Greenhouse”) Platform for Initiatives opened in Slovyansk. Modeled on Freedom Home, Teplytsia nurtures democratic ideas and civic activism, the very ideas forbidden by the Russian-backed separatists. Housed in a former separatist base, it “not only serves as a platform for cultural and artistic development, but also plays the role of a watchdog organization making local government more transparent and accountable,” Teplytsia platform coordinator Liubomyr Leshchuk told me.

Both Freedom Home in Kramatorsk and Teplytsia in Slovyansk serve as cultural bridges between eastern Ukraine and the rest of the world. The platforms host famous cultural and public figures to connect young people with larger intellectual and cultural trends. Recent guests have included leading Ukrainian poet Sergii Zhadan, singer Oleksandr Polozhynskyi, and former Minister of Economic Development Pavlo Sheremeta.

Denys Bloshchynskyj at one of the events organized by the Fund, 2015. Credit: Artem Getman.

4) Promoting Ukrainian Culture and Education Through Film and Music

During the Euromaidan, the From the Country to Ukraine Fund “realized that most children and young people do not fully understand what Ukraine is. They know very little about their history, culture, traditions and almost nothing about Ukraine that’s trendy and modern,” said Denys Bloshchynskyi, executive board member of the fund and leader of the music group Nesprosta. In response, the fund launched a series of educational and culture initiatives in the Donbas.

“Unfortunately the war in Ukraine will last for a while. Therefore, we have to work on winning the war in our heads – with our attitude towards culture, with our own critical thinking, with our willingness to act with no regard to anyone except our internal feelings,” Bloshchynskyj said.

Open Ukraine film festival opening, 2014

The Fund prioritized education and has brought modern Ukrainian authors, actors, and musicians to eastern Ukraine.

A modern Ukrainian rock band “Nesprosta” performed in Slovyansk, 2014.

Music of Dignity Concert promoting Ukrainian modern artists, April 2015.

5) Promoting Government Transparency

For decades, the Soviet system propagated the idea that nothing depends on the common man. Ukrainians still do not fully understand that they are the government and that they can solve problems by working with like-minded people.

The Kyiv-based Center UA seeks to change this mentality in the Donbas by “teach[ing] the residents the tools of protecting their interests, given to them by Ukrainian legislation,” according to Valentyn Krasnopiorov, initiatives director. The organization has influenced high-level officials and brought local changes already. Pavlo Ostrovskyj, a field coordinator for the Strong Communities of Donetsk NGO, (below) brought down a corruption scheme at the Druzhkivka Water Supplier that was laundering millions from the city budget. Today, he travels across the region and through case studies he teaches future monitors how to control local budgets.

In addition, the initiative is forming teams of local activists who want to hold local authorities accountable and promote positive change in their communities.

6) Assisting Internally Displaced People

Officially Ukraine has 1,381,953 internally displaced persons but experts believe that number is higher. Given the government’s inability to promptly and effectively respond to the needs of this vulnerable population, Donbas SOS has provided legal aid, social reintegration, information about registration procedures, and permanent and temporary settlements. In its first year, fifty volunteers offered consultations to 25,000 IDPs, evacuated 3,500 persons from conflict zones, and provided more than 10,000 kl of humanitarian packages in the Donbas.

7) Bringing Free Media to the Donbas

To provide Donbas residents with an alternative source of information, a group of journalists started the Donetsk office of Hromadske TV (Donbas Public TV) in May 2014. It enabled citizens to finally gain access to free media. HromadskeTV brings residents up to speed about current events and serves as a platform for civic initiatives to spread the word about their activities and services.

8) Promoting National Dialogue

As Ukraine continues to rebuild after the Euromaidan and the war in the east, it’s necessary to have a long-term strategy. The International Center for Policy Studies (ISPS), a Kyiv-based think tank, conducts national studies, polls, and roundtables to better understand societal divisions.

Given the relentless and harsh propaganda about differences between east and west, ISPS has focused on the eastern front. By engaging local citizens in the process of creating a common vision for the future, the initiative is helping reintegrate the region and lay a foundation for unity based on common values. ISPS co-organized the Forum Donbas, an effort of civil society, government, and international partners, to address pressing problems in the Donetsk and Lugansk regions.

Donbas Forum in Slovyansk, May 2015

Yuriy Didula manages the Lviv Education Foundation‘s eastern Ukraine portfolio.

Image: A few weeks after Ukrainian soldiers retook Kramatorsk, Lviv Education Foundation set up a volunteer camp there made up of more than 80 volunteers from western and central Ukraine who helped locals rebuild homes and social capital. The camp was unique: in the morning, volunteers performed hard physical labor, while in the evening, they’d gather at a bonfire and chat with locals, which chipped away at the pernicious stereotypes that exist between Ukrainians in the east and west. Credit: Lviv Education Foundation