The Rand Corporation has just issued a publication, A Consensus Proposal for a Revised Regional Order in Post-Soviet Europe and Eurasia, with twenty-one authors and seven editors. The contributors come from the United States, the European Union, Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, Belarus, Moldova, and Armenia. The main editors appear to be Samuel Charap and Jeremy Shapiro. It offers an easy and well-edited read.

The idea of this project is to do something about the disorder in post-Soviet Europe and Eurasia caused by the breakdown in relations between Russia and the West. The authors are quite ambitious, being intent on offering “a comprehensive proposal for revising the regional order,” addressing the security architecture, economic integration, and regional conflicts. The project initiators are the RAND Corporation and the German Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

There is always a value in a “track 2 exercise” with the other side, to meet and to try to understand one another. I know and appreciate two of the three Russians involved, but as every diplomat knows, this does not mean that one should necessarily try to reach an agreement. Often, it is more useful to meet to clarify one’s disagreements.

Subscribe for the latest on Russia

Receive updates for events, news, and publications on Russia from the Atlantic Council.

At present, Russia and the West share few values short of wanting to avoid mutual destruction. To try to reach any consensus with the enemies of democracy should be considered as indecent today as it was in Munich in 1938. To reach a consensus with the enemies of good values is not desirable but harmful, even while recognizing the usefulness of discussing issues that can be relevant for parties supporting opposing principles. Such issues are to avoid nuclear war, to renew the new START agreement, and to agree on inspections to avoid war by misunderstanding.

A key question for an exercise of this nature should have been to identify key dividing lines. Where are the differences greatest between the West, the “in-between” countries, and Russia? By insisting on reaching a consensus, the organizers conceal rather than illuminate these critical questions. Why do something that is neither practical nor relevant? Worse, the report argues for the non-alignment of the “in-between” countries, which can only benefit Russia. Don’t they understand that?

Let us take a step back and ask, what are the main problems in Eastern Europe? The obvious answer is Russian military aggression, manifested in Georgia in 2008 and in Ukraine since 2014. Needless to say, the report’s consensus approach implies that the words “Russian aggression” are precluded. Why write a report that does not even mention reality?

There are also major problems in the choice of wording elsewhere in the report. This includes references to “ongoing trade disruption” when addressing Russian trade sanctions against neighboring countries. How can anybody solve anything without daring to call things by their name? In five years, Russia has slashed its trade with Ukraine by three-quarters because of its vicious sanctions against Ukraine.

The report’s convoluted wording presents this Russian trade aggression rather differently: “Russia suspended the CIS FTA regime toward Ukraine in 2016, after the EU-Ukraine DCFTA entered into force arguing that Ukraine’s participation in both would pose risks for Russia’s own economy. In addition to this move, which drastically increased tariffs on Ukrainian goods, Moscow also banned agricultural imports from Ukraine; in turn, Kyiv banned a range of Russian imports, ranging from meat to alcohol products” (p. 42). Really? This presentation suggests that both sides were equally bad, which is not true. The authors must know that the Russian trade sanctions against Ukraine started in July 2013, before turning ever more vicious.

Eurasia Center events

A third problem with the report is that it is so old-fashioned. It fails to mention all the modern features of Russian aggression, its hybrid warfare through cyber, disinformation, and energy, not to mention corruption, oligarchs, and dark money. If you do not even touch upon the rising concerns, you can do nothing about them.

What should be done in a sensible Track 2 exercise? First of all, the real differences between Russia’s and the West’s aspirations should be specified, not papered over. That is what real diplomats do. Second, the opposing sides should present their proposals for dealing with these actual problems. Because of the report’s consensus approach, neither side makes any relevant statement. This shows how by being too kind, you risk achieving nothing. Third, the West’s main endeavor should be to alter Russian incentives, increasing the cost of all forms of Russian aggression so that it appears no longer beneficial. This would imply arming Ukraine more, imposing tougher sanctions on Russia, while insisting on more financial transparency to stop Russia’s hybrid warfare.

I have been there and tried the consensus approach, but today the divide between Russia and the rest is far too wide, turning such projects into hypocrisy.

Anders Åslund is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and the author of “Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy”

Further reading

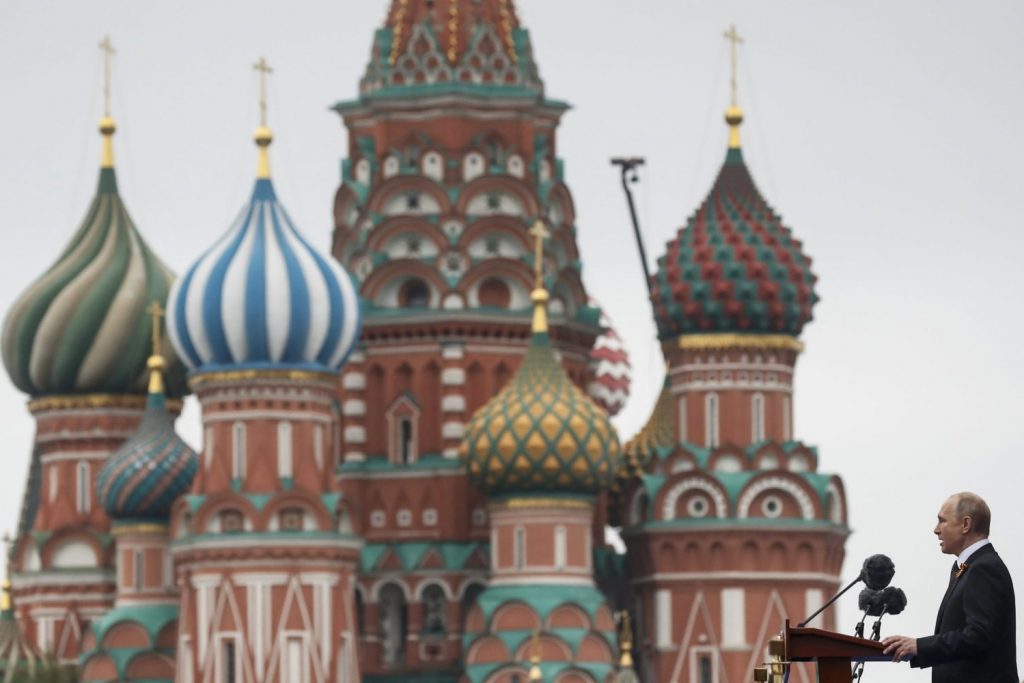

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin delivers a speech in front of St. Basil's Cathedral during the Victory Day parade, which marks the anniversary of the victory over Nazi Germany in World War Two, in Red Square in central Moscow, Russia May 9, 2019. REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov