Around two dozen high-profile journalists were recently detained in Belarus in one of the biggest intimidation campaigns in years. The details of this sudden and surprising sweep highlight growing tensions in the country, where the authoritarian regime of President Alexander Lukashenka is seeking a balance between necessary pro-market reforms and its preservation.

The detention of the journalists—on suspicion of hacking the computer systems of state-run news agency BelTA—started on August 7. By August 9, they had been brought in for questioning by the Belarus Investigative Committee, the country’s main law-enforcement agency. Overall, eighteen journalists were detained.

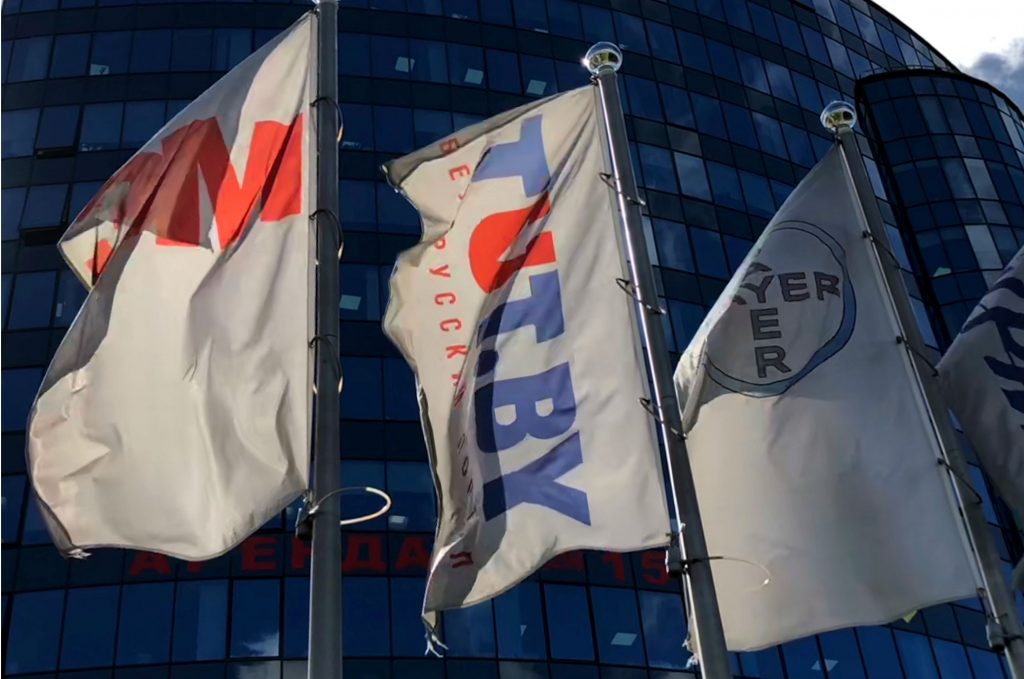

Tut.by, one of Belarus’s largest online news outlets, was the primary target, along with the only privately run news agency, BelaPan, the academic newspaper Nauka, the real estate news website Realt.by, and even the state-owned newspaper Kultura. Law enforcement agents raided their newsrooms. At some, they confiscated computers and detained staff; they allowed others to continue their work after the search.

By August 10, all detainees had been released. The Investigative Committee publicly promised to continue its investigation following the sweep.

The Belarusian authorities accuse the journalists of illegally obtaining content from the paywalled services of BelTA, a state-run news agency. The Investigative Committee opened a criminal inquiry after an Interior Ministry investigation uncovered “15,000 cases of unauthorized access” to BelTA’s content.

Authorities claim that the investigation was launched following a complaint from Irina Akulovych, BelTA’s editor-in-chief. Hours after the first detentions and searches, SB-Belarus Today, the presidential administration’s mouthpiece, published a detailed report exposing “the mass stealing of content from BelTA’s paid subscription.” It included a wiretap recording of Tut.by journalists acknowledging illegal access. Later they confirmed its authenticity.

Despite a torrent of accusations from civil society and human rights groups, the Belarusian government denies any political motivation for the recent raids. However, there are several clear signs suggesting that this is an organized intimidation campaign by the government against the free press. First, the content of the case—unauthorized access, not an unusual practice in journalism—doesn’t match the accusations, which are of computer hacking. And many of the journalists were detained for seventy-two hours, an unusually long time for a minor offense. Finally, many of the journalists were wiretapped even before the investigation was launched.

It’s impossible to view this crackdown in a vacuum; it is the product of a transitioning Belarus, in which the forces of modernization are clashing with efforts to slow down or even halt the changes.

Since its independence in 1992, Belarus has been one of the world’s most hostile places for journalists; it ranked 155th out of 180 countries on Reporters Without Borders’ 2018 World Press Freedom Index. However, rising public discontent in the last year has provoked mass demand for unbiased reporting. In the spring of 2017, rarely-seen anti-government protests filled public spaces across the country, and the pool of independent journalism expanded around the country, fueled by opportunities provided by then-accessible social media platforms.

Record numbers tuned in to live streams of the protests, with some of the journalists managing to broadcast during detention, even from within police stations. This was the first time that Belarusian journalists had managed to be so audacious, working in the same way that journalists in democratic countries do. The Belarusian authorities stepped up their pushback, blocking websites, adopting an even more draconian media law, and subjecting independent journalists to an unprecedented wave of fines. But the 2017 crackdown failed to reach the level of the previous one in 2011.

Today, the ruling regime in Belarus cannot respond as harshly to the free press as it has in the past. After all, Lukashenka’s regime is simultaneously forced to use the media to counter increasing Russian propaganda within the country.

Following Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, a petrified Minsk reined in its economic and political dependence on Moscow and took a friendlier approach not only to Ukraine, but also to the West and China. In response, Russia has revved up its notorious propaganda and disinformation machine to ensure that Belarus keeps its distance from the outside world.

This has forced Lukashenka into a “necessary evil” compromise: Tut.by’s editor says that authorities tolerate its moderately critical coverage because they know readers would turn to more radical, foreign-based sources if the site were not allowed. This tolerance, however, does not fully protect Tut.by’s journalists, as the recent intimidation campaign suggests.

In 2017, the authorities allowed the return of several independent print newspapers. State distribution networks are now openly cooperating with both Narodnaya Volya and Nasha Niva, the country’s leading opposition print publications.

But the recent crackdown suggests that the Lukashenka regime feels freedom of speech is developing too quickly amid unprecedented pro-market reforms. The growing voices of independent journalism and civil society do not exist in isolation from other changes occurring in Belarus. Following a geopolitical shift away from total dependence on Russia, the government also embarked on bold pro-market reforms. The Soviet-era economy had run its course by the early 2010s. Falling oil prices and economic turmoil in Russia, exacerbated by the country’s aggressive military advances, forced Belarus to look elsewhere, and IMF bailout talks were restarted in exchange for economic reforms. The liberalization of the Belarusian economy in the last three years ended a deep recession, started one of the biggest IT industry booms in Europe, and pushed the country into the top forty on the World Bank’s Doing Business Index, where it occupies the sixth position among former Soviet states.

However, calling Belarus “Europe’s Singapore” would be premature, analysts warn. The pace and depth of reforms are not yet sufficient, and economic dependence on Russia remains substantial.

At this critical time, the EU has leverage in pushing back against crackdowns on liberties in Belarus.

The following months will only exacerbate growing tensions between Russia, which compensates for economic turmoil by doubling down on aggressive colonial rhetoric, and the Belarusian regime trying to reclaim some autonomy from Moscow. The row creates a unique opportunity for EU states to enter into a strategic alliance with Belarus to counter Russia’s increasing political and economic meddling in European democracies. This alliance won’t bring an overnight change to autocratic Belarus, but it will reinforce those positive steps that Belarusian civil society has already taken toward a more open country.

Economic reforms, a stronger voice for the independent press and civil society, even the fact that the ongoing intimidation campaign against journalists is much less harsh than it was in 2011, are signs that Belarus is moving in a promising direction. The BelTA crackdown is a simple reaction of an authoritarian government to the speed of positive transformations, but it doesn’t have the capacity to reverse them. None of it would be possible without the recent rapprochement with the EU that lifted harsh economic and political sanctions against Minsk in 2016.

Now is the time for the EU to double down on the carrot approach, while also rolling out the stick. The increase of further political and economic support (including through the IMF framework) must go hand in hand with more forceful corrective measures in case of pushback. In light of deteriorating relations with Russia, Belarus might become a new ally of European countries guarding themselves from increasingly aggressive meddling from Moscow. But this alliance cannot compromise the foreign policy values shared by Europe and must be based on smart conditionality; Lukashenka must allow further pro-democratic changes in Belarus if he wants more EU support.

Maxim Eristavi is a nonresident research fellow at the Atlantic Council and co-founder of Hromadske International, an independent news outlet, based in Kyiv, Ukraine. This article has been shortened and edited with the author’s permission. Utrikes Magasinet (Sweden) published the original version.

Image: The logo of privately owned independent news website "Tut.by" is seen on a flag (C) in front of the office building in Minsk, Belarus August 7, 2018. REUTERS/Vasily Fedosenko