How has Ukraine changed since the Euromaidan Revolution?

How has Ukraine changed since the Euromaidan Revolution?

In attempting to answer this question, I’ve used the governance-related categories in Freedom House’s Nations in Transit study, which tracks the reform record of post-Communist countries in Europe and Eurasia, and supplemented them with a few of my own. (Full disclosure: I’ve been involved in the Nations in Transit project since its inception in the mid-1990s.)

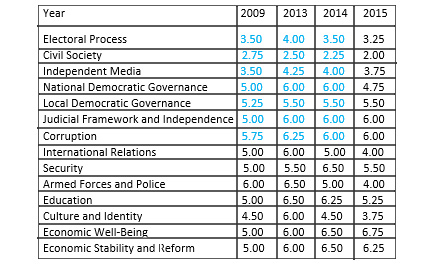

Freedom House assigns scores between 1 and 7 (with 1 being the best and 7 the worst) to seven institutional categories: electoral process, civil society, independent media, national democratic governance, local democratic governance, judicial framework and independence, and corruption. As these categories focus primarily on politics, I’ve added seven more to round out the picture: international relations, security, armed forces and police, education, culture and identity, economic well-being, and economic stability and reform. (Unlike Freedom House, which assigns scores to Ukraine together with its Russian-occupied territories, I will assign scores only to “free” Ukraine.)

In the chart below, I’ve listed Freedom House’s scores for its seven institutional categories for three years: 2009, the last year of “Orange” government; 2013, the last year of former President Viktor Yanukovych’s government; and 2014, the year of post-revolution instability and war. I’ve added my estimates for the seven additional categories for those three years, as well as for all fourteen categories for 2015, the year of post-revolution consolidation, as Freedom House’s scores for this year haven’t yet been published. For the sake of clarity, Freedom House’s scores are in blue.

Across the board, Freedom House’s scores deteriorate sharply between 2009 and 2013, then improve slightly in 2014, after Yanukovych’s departure. That’s not surprising: Yanukovych was a disaster for Ukrainian politics, and although his departure improved things, that improvement was marginal, given the conditions of post-revolution instability and war in the east.

My own scores for 2009, 2013, and 2014 both reflect and deviate from this trend. My seven categories show across-the-board declines between 2009 and 2013, as well as significant selective declines between 2013 and 2014. On the other hand, Ukraine’s international relations improved significantly in 2014, as the country became a strategic concern of the West; so, too, did its armed forces, which developed into a genuine fighting force, and its culture and identity, with the former becoming freer and the latter becoming more consolidated. Education improved only slightly in 2014, mostly because Yanukovych’s education minister, Dmitri Tabachnik, left office. However, security, economic well-being, and economic stability and reform all experienced large drops, mostly as a result of the war with Russia and turmoil in the east.

In contrast to revolutionary and war-torn 2014, 2015 was a year of post-revolution consolidation, demonstrating improvements in many categories. The score for electoral process improved in light of October 2015’s largely free and fair local elections. Civil society became even more active, and the media became a tad more independent. National democratic governance improved significantly, as the government of President Petro Poroshenko and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk reestablished control over the country and began functioning as a genuine government.

Local governance remained unchanged (given the planned decentralization, it could change for the better in 2016), as did judicial framework and corruption. Ukraine’s international relations, security, and armed forces and police improved, as the war became a stalemate and the West continued to value Ukraine; culture and identity, as well as education, also improved. The economy was a mixed bag: living conditions declined greatly, while macroeconomic stabilization and some tax reform merited a slight improvement from 2014.

In sum, even if my scores are too generous, it is clear that Ukraine experienced improvements of some kind in ten out of fourteen categories. Only four categories were characterized by a lack of positive change: local governance, judicial framework, corruption, and economic well-being. Significantly, the lack of any noticeable improvement in just these four categories explains why many Western policymakers and analysts remain dissatisfied with Ukraine’s progress, and why most Ukrainians insist that “nothing has changed.”

Western policymakers and analysts are unhappy with Ukraine’s progress because they prioritize corruption, where no improvement whatsoever is visible. Although the West must continue to pressure Kyiv to adopt serious anticorruption measures, Western governments and organizations may also want to reconsider their “fetishization” of corruption.

For starters, no country ever moves with lightning speed from a condition of deep corruption to no corruption. The struggle against corruption, in Ukraine and elsewhere, is a long-term and arguably never-ending process. Second, corrupt countries can and do change for the better. Ukraine is proof of that, as is virtually every country in the world, including the United States. Indeed, corrupt countries can experience rapid economic growth (China), enjoy democracy (India), and be pleasant places to live (Italy). Finally, a truly radical, full-scale attack on corruption would almost certain impair Ukraine’s democratic institutions.

Obviously, profoundly corrupt countries that remain profoundly corrupt are probably dooming themselves to permanent underdevelopment, but that eventuality is likely only in authoritarian states like Zimbabwe and Russia, where dictators impose such a trajectory on the population. Ukraine’s strength has been its civil society and independent media, which, even during the worst days of President Leonid Kuchma in the 1990s or Yanukovych in 2010-2013, made it difficult for dictators to ignore society’s preferences.

Ukrainians want two things above all. First, after twenty-five years of penury, they want their lives to finally get better. Instead, GDP declined by over a fifth between 2014 and 2015. The reason may be war and not government inaction, but Ukrainians cannot be blamed for holding their President and Prime Minister accountable.

Second, after two impressive displays of “people power” in 2004 and 2013-2014, Ukrainians want justice. They want the corruptioneers, thugs, oligarchs, and authoritarians who limited their livelihoods for twenty-five years and opposed their revolutionary upheavals to pay. The Euromaidan Revolution in particular was about justice, and it raised popular expectations enormously. Instead, not a single Yanukovych crony, Party of Regions bigwig, oligarch, or shooter of demonstrators has been prosecuted.

In sum, while Ukrainians’ well-being has deteriorated sharply since the Euromaidan, their enhanced desire for justice has remained unsatisfied. Ukraine may have become a better place according to the above 14 indices, but Ukrainians don’t care—and they are right.

There are signs that things may be changing. The Ukrainian parliament displayed remarkable dynamism in the last few days, as it dismissed 227 judges, passed a law forbidding workplace discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, created a State Bureau of Investigation, and adopted a measure replacing the corrupt Soviet-era militia with a national police. These steps could amount to little, as is often the case in Ukraine, or they just might herald a shift, however halting, toward genuine anticorruption reform.

There are several things to watch for, in particular. We’ll know Kyiv is serious about justice if the already existing Anti-Corruption Bureau is paired with an independent procurator and independent judges and if Poroshenko replaces the current Procurator General, Viktor Shokin, a man virtually everyone believes is corrupt, with a genuine reformer. And we’ll know Kyiv is serious about reforming the economy—and promoting popular welfare—if the 345 state-owned firms that are at the core of oligarchic schemes for robbing the state are privatized by early 2016.

Will Ukraine finally get serious? Next year, 2016, could show real movement toward addressing Ukrainians’ demands for an improvement in living standards and justice for three reasons. The indispensable West appears to be losing its patience, and Ukrainian elites know it. Increasing numbers of Ukrainians are also losing their patience, with some even insisting that a third Maidan revolution is necessary. Finally, the high probability of continued Russian aggression in the east should serve as a constant reminder to Kyiv that it really has no choice but to change—however slowly and fitfully.

Alexander Motyl is Professor of Political Science at Rutgers University-Newark.

Image: Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko spoke at “Prevent. Fight. Act,” an international anticorruption conference November 16 in Kyiv. Credit: Presidential Administration of Ukraine.