Crimean Tatars’ unending struggle for freedom has been nothing less than epic, and much of it is represented in the long life of Mustafa Dzhemilev. Finally, a film producer has recognized his story for what it is: a compelling tale of historic sweep featuring a legendary protagonist of distinguished bearing.

Crimean Tatars’ unending struggle for freedom has been nothing less than epic, and much of it is represented in the long life of Mustafa Dzhemilev. Finally, a film producer has recognized his story for what it is: a compelling tale of historic sweep featuring a legendary protagonist of distinguished bearing.

Tamila Tasheva, cofounder and chairwoman of the CrimeaSoS human rights organization, produced the full-length docudrama Mustafa, which was released in 2016 at the annual Kyiv Molodist International Film Festival and screened last year at the Ukrainian Institute of America in New York. Tasheva recently showed the film together with Dzhemilev before a Washington audience at the National Endowment for Democracy, which helped fund the film. Following the movie, a panel of experts discussed Crimea’s history and current situation.

The film, available on YouTube with English subtitles, chronicles the life of Dzhemilev, now 73. It opens with his family’s 1944 deportation from Crimea to what was then the Uzbek Republic in Stalin’s Soviet Union. The story moves through his youth of daring activism in an effort to return Tatars to Crimea, a cause that landed him in Soviet prison camp for fifteen years and included a record-setting 303-day hunger strike. The movie concludes with the struggles he and his people have faced since then. In a brutally ironic repeat of history, the Tatars again have confronted repression since the 2014 Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea. And again, Dzhemilev and many of his compatriots have been forced from their ancestral homes.

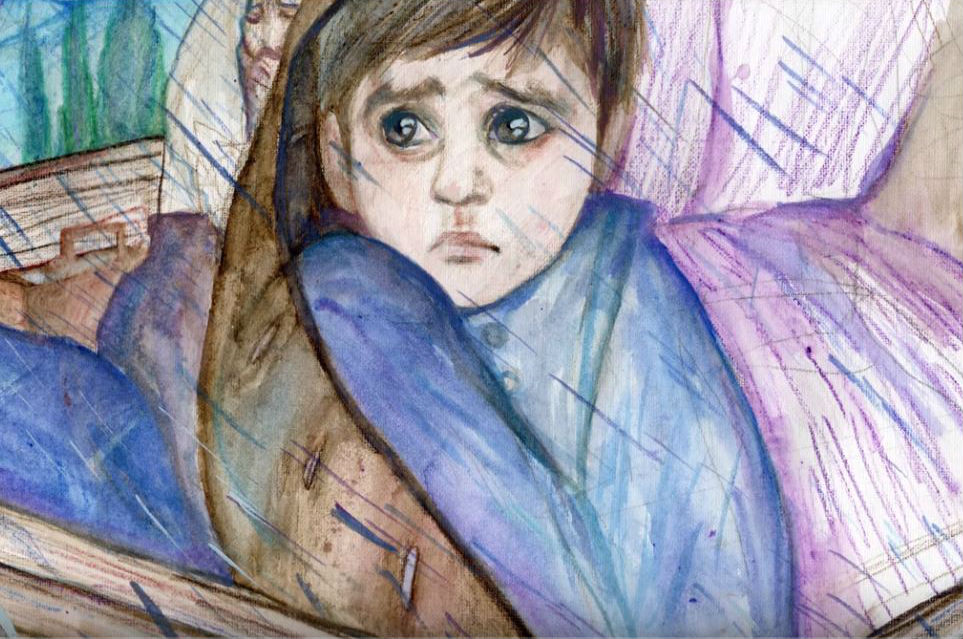

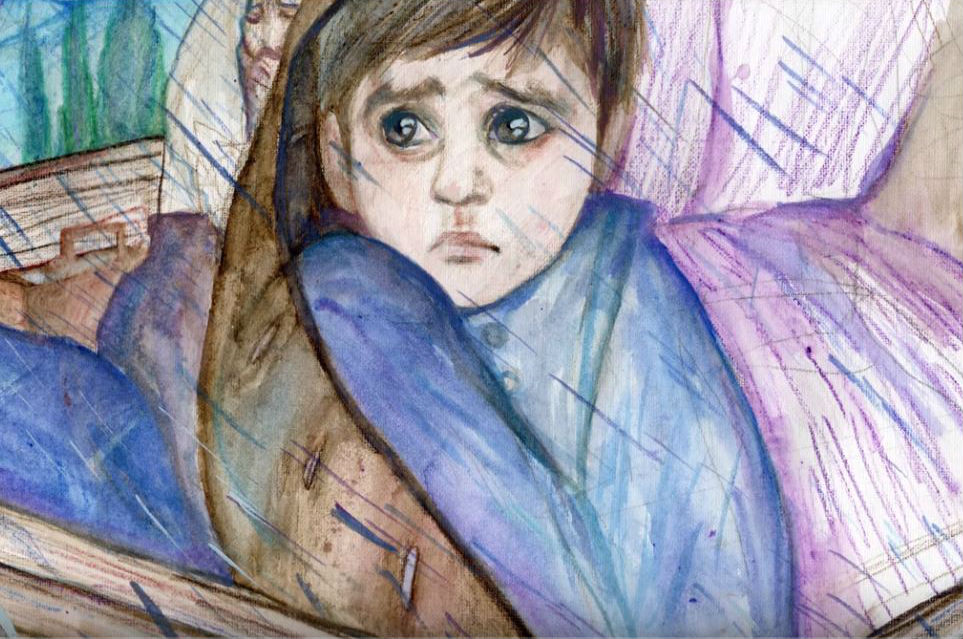

The film is a collaborative project between Tasheva; director Ahmed Sarykhalil; pianist, composer, and sound producer Fima Chupakhin; and Ukrainian journalist, essayist, and historian Vakhtang Kipiani. It intersperses dramatizations with interviews featuring his activist peers and drawings used to personalize events of the time.

The actor who plays Mustafa as the imprisoned hunger-striking activist is a convincing young version of Dzhemilev. The docudrama occasionally resorts to literary license, such as the repeated appearance of a backgammon board in his prison cell to represent Dzhemilev’s enjoyment of the game, even though he never had that luxury in detention. But those moments are outweighed by the sweep of the story, the haunting music, the testimony of human rights legends, and the beautiful artwork.

Among the icons helping to tell the story is Lyudmila Alexeyeva, a Russian historian and founding member of the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group, who remains active in the fight for human rights in Russia today. “We heard about Mustafa Dzhemilev also because he was arrested many times,” she said.

The movie caught many of the most critical moments in Dzhemilev’s political life. Together with friends, Dzhemilev established his Union of Young Crimean Tatars in the Uzbek Republic when he was eighteen to campaign for human rights and for their return to Crimea. He was arrested for the first of six times in 1966. Among those who spoke out in Dzhemilev’s defense was the Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov, who sent him a note in 1975 appealing for him to end his hunger strike, arguing that his death would only benefit the regime. Another arrest came in 1983, when he tried to go back to Crimea for his father’s funeral.

Tatars finally began to move back to Crimea after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and enjoyed twenty-three years of relative freedom—until the Russian annexation in 2014. Though Ukrainian leaders and Russians living in Crimea provided little support during that time, Dzhemilev is clear about his priorities.

“Whatever happened there, we lived in a free country after all, and freedom cannot be exchanged for any material goods,” he told Radio Svoboda in 2014. That year, newly elected Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko appointed him Commissioner of the President of Ukraine for the Affairs of Crimean Tatars.

After the screening in Washington, NED President Carl Gershman awarded Dzhemilev the organization’s Democracy Service Medal “in recognition of his spiritual strength and devotion to the cause of democracy, and for his unyielding defense of the human dignity and national integrity of his people, the Crimean Tatars.”

“I believe that this medal belongs to the entire Crimean Tatar nation, a nation which is very courageous and brave, which managed for decades to resist such a strong superpower, and which now is also resisting this audacious, vile, cruel aggressor,” said Dzhemilev. “Our country, our people, badly need solidarity and support these days.”

Jorgan Andrews, director of the US Department of State Office of Eastern European Affairs, pledged American solidarity “with Ukraine, the people of Crimea, and the Crimean Tatars,” and cited “the horrific violations of human rights and other injustices committed by the Russian occupiers in Crimea.”

The persecution continues. In December, Amnesty International reported a “brazen crackdown” in which occupying Russian authorities in Crimea tried seventy Crimean Tatars at once.

“Russian authorities have already forcibly exiled or jailed Crimean Tatar leaders, banned their representative body, the Mejlis, and stifled the Crimean Tatar-language media,” said Oksana Pokalchuk, Amnesty International Ukraine’s executive director. “With this latest move, they are aiming to shut down individuals’ expressions of dissent and deprive them of the right to voice their dissatisfaction.”

And in May, the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group reported a series of armed searches and arrests of Tatars, including Server Mustafaev, coordinator of the Crimean Solidarity social movement. Such raids have become common on the peninsula.

Speakers at the event also noted the current hunger strike by Oleg Sentsov, the Ukrainian filmmaker arrested in Crimea in 2014 and sentenced by Russian occupation authorities to twenty years in prison based on a supposed confession extracted under torture. He aims to draw attention to the sixty-four Ukrainian political prisoners being held by Russia, many of them Crimean Tatars.

A new generation of activists is continuing the fight in Crimea, but they acknowledge they owe a huge debt to the region’s first activist, Mustafa Dzhemilev.

Viola Gienger is a freelance journalist who has covered foreign affairs, defense, and international security for Bloomberg News and led programs and training for independent media in the former Soviet Union and the Balkans. She most recently was senior editor/writer at the US Institute of Peace.

Image: A screenshot from the film, "Mustafa," a docudrama about the long life of Crimean Tatar activist Mustafa Dzhemilev.