Resolving the conflict in Ukraine should be a higher priority for the United States and Europe than addressing the civil war in Syria, said Archbishop Zoria Yevstratiy, representative of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church Kyiv Patriarchate, during a visit to Washington, DC. “I’m very sorry about the Syrian people, but Ukraine can’t be compared. Syria never played a key role in global or even regional affairs,” Yevstratiy said in an exclusive interview with UkraineAlert on October 26.

Resolving the conflict in Ukraine should be a higher priority for the United States and Europe than addressing the civil war in Syria, said Archbishop Zoria Yevstratiy, representative of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church Kyiv Patriarchate, during a visit to Washington, DC. “I’m very sorry about the Syrian people, but Ukraine can’t be compared. Syria never played a key role in global or even regional affairs,” Yevstratiy said in an exclusive interview with UkraineAlert on October 26.

The war in Ukraine has displaced more than 1.7 million people, and 10,000 people have been killed. The humanitarian crisis in Ukraine’s east has not generated much international assistance relative to similar conflicts and is no longer top news. Nonetheless, said Yevstratiy, it has strategic importance.

“Ukraine is a big country in Europe located between Russia and the rest of Europe. And in essence it is a wall standing between the civilized and uncivilized world,” he said.

What religious freedom?

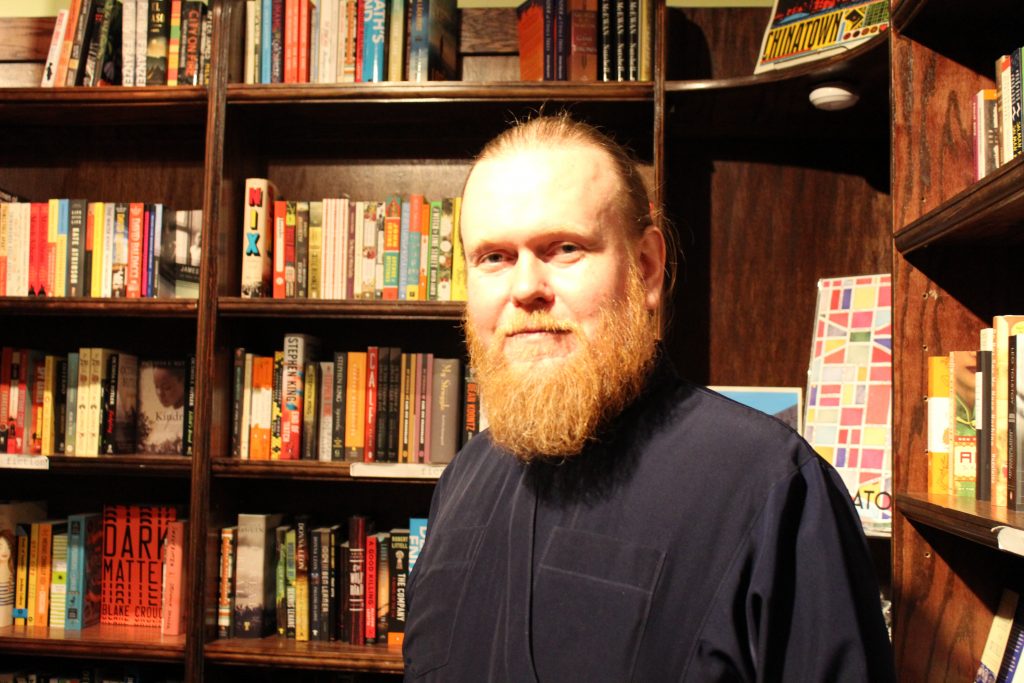

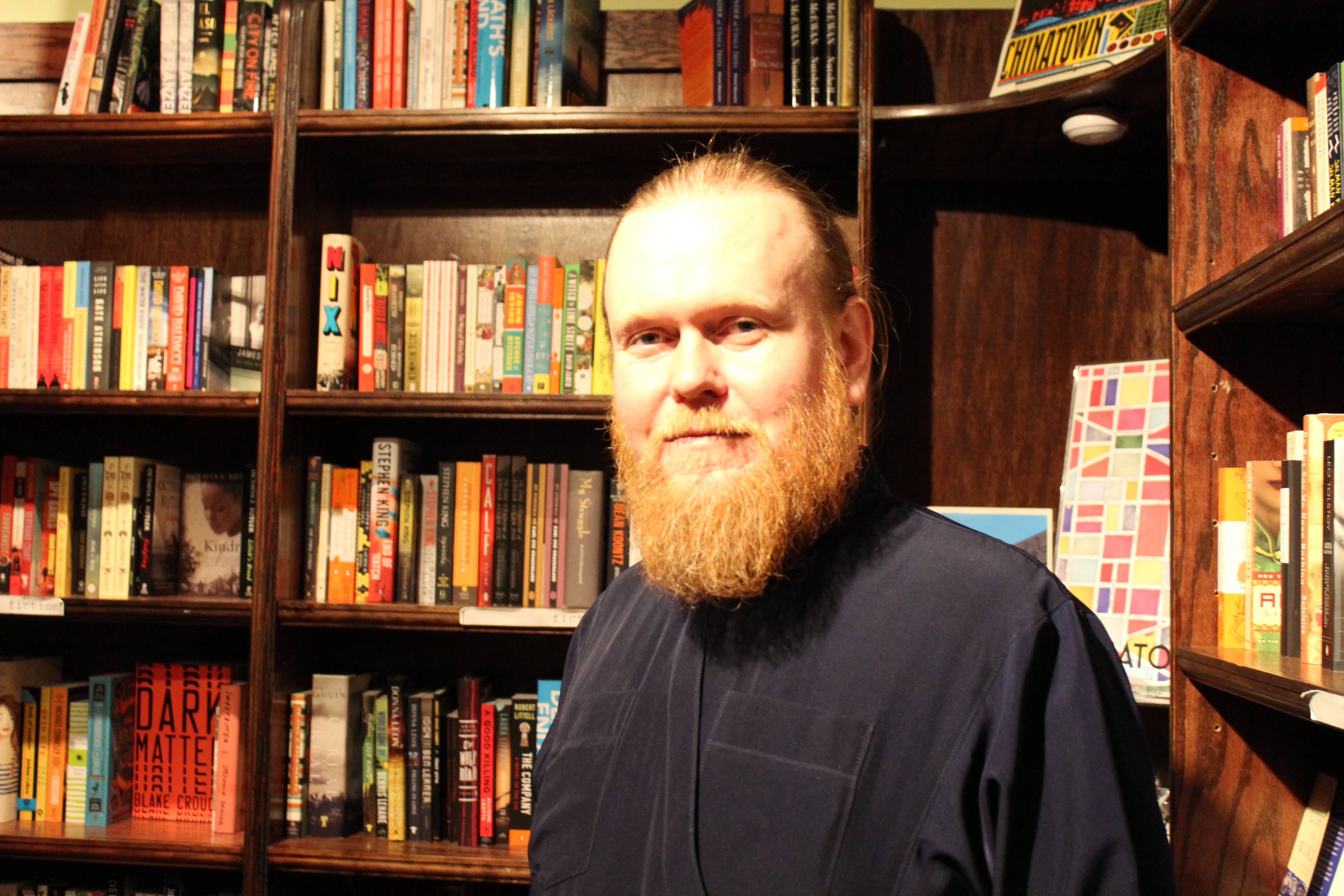

Yevstratiy, who has lively eyes and bright red hair, was in Washington for a conference on religious freedom sponsored by the Center for US-Ukrainian Relations. As always, he was ready to discuss Ukraine’s place in global affairs, the lack of religious freedom in Ukraine’s occupied areas, and the struggles facing the Kyiv Patriarchate.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the Patriarchate of Moscow had double the number of parishes in Ukraine as in Russia. As Ukraine became independent, a number of communities broke with the original church and formed the Kyiv Patriarchate. The remaining churches renamed themselves the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine, the Kyiv Patriarchate has seen tremendous growth in Ukraine, mostly in cities, according to Yevstratiy. Approximately 42-44 percent of Ukrainians support the Kyiv Patriarchate, while 15-20 percent support the Moscow Patriarchate. In cities with 50,000 or more people, support for the Kyiv Patriarchate nears 60 percent.

Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and other senior churchmen have supported the Kremlin, which has only increased the appeal of the Kyiv Patriarchate, he said.

In the Donbas, there’s no united policy on religion, Yevstratiy explained, which puts power in the hands of local warlords. Leaders there view all Catholics, Protestants, and anyone outside of the Moscow Patriarchate as agents of US and Western influence.

In Crimea, the situation is different. Russia’s policy there is to control all religions regardless of their faith, Yevstratiy said. “For [Russian President Vladimir] Putin, Crimea is a big military base. His goal is to have as many loyal people there as possible.” And he’ll kick out those who object.

The occupying Russian authorities required all religious organizations to register by January 1, 2016, although most religious minorities, including the Kyiv Patriarchate, defied its orders. Additionally, only Russian citizens are allowed to register religious organizations. Consequently, those religious leaders who refused Russian citizenship, or were citizens of other countries, face expulsion.

The Kyiv Patriarchate didn’t register because the church doesn’t recognize Russia’s annexation of Crimea. As a result, the Kyiv Patriarchate, and every other religious body not loyal to the Kremlin, is in serious danger in Crimea. Unregistered property is subject to nationalization.

The US State Department has sounded the alarm, publicly condemning religious abuses carried out by Russian occupying authorities in Crimea. Kyiv Patriarchate priests have said they are under constant surveillance by Russian authorities, who have forced them to provide lists of churchgoers and ordered them to sign documents affirming their identity and church membership.

Additionally, rents have been artificially raised to make it almost impossible to operate. In one instance, Russian authorities forced property owners to break leases with the Kyiv Patriarchate, and consequently three parishes were forced to close.

The situation is even worse for the remaining ten Kyiv Patriarchate churches in Russia itself. In October, the Moscow Regional Court ordered the Ukrainian Church of the Holy Trinity in Noginsk to be demolished within four months at the expense of the Ukrainian diocese.

“What’s happening to this community is part of a Russian campaign to deny Ukrainian identity or the subjection of Ukrainian ethnicity,” Yevstratiy said. Russia has no Ukrainian schools and the Ukrainian Literature Library in Moscow has been shuttered. Its director has been charged with inciting extremism and ethnic hatred because the library allegedly included books by Ukrainian ultranationalists that are banned in Russia. The trial against her began on November 2.

“Russia is trying to have nothing Ukrainian in the country,” he added.

Church politics

In June, Ukraine’s parliament called for an independent church just as Orthodox Christian bishops began arriving for a historic church conference in Crete. The Kyiv Patriarchate is not recognized by Orthodoxy’s world center, the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

“Today we are working with the Constantinople patriarch and we would like Constantinople to recognize our church. This would open the way for the unification of the Ukrainian church,” said Yevstratiy. However, the patriarch is “very cautious, very careful,” said Yevstratiy, and is afraid to make any concrete moves that might worsen the situation.

Moscow refused to participate in the Crete conference, although it influenced three other churches that were present. Yevstratiy sees this is a classic example of how Putin operates: he’s always looking for ways to increase Russia’s power.

On October 19, Russia opened an expensive new cultural center and cathedral next to the Eiffel Tower in Paris “to show that Russian Orthodoxy dominates in Western Europe, not Constantinople Orthodoxy,” Yevstratiy theorized. While not yet complete, the 160 million euro project will promote the interests of the Moscow Patriarchate, with whom Russia’s Foreign Ministry regularly meets and collaborates. Paris has been the center of Russian immigration in Europe and France has generally been more loyal to Moscow than other European countries.

No free pass

While quick to condemn Putin’s aggression, Yevstratiy admitted that there’s much to be done in Ukraine.

He said that the ruling elite in Kyiv understand that this period after the Euromaidan revolution is their last chance to deliver on the promises of reform. “If our current leadership loses this chance, they won’t have anywhere to go. Russia won’t take them,” he acknowledged.

According to Yevstratiy, the church frequently talks about the scourge of corruption. “[Corruption in Ukraine] is worse than the Kremlin, because the Kremlin is trying to destroy us from within as an external threat,” he said. “But the internal threat is much more difficult to fight.”

“Society will change when the legal path to enrich oneself will be simpler than the illegal way,” he said. Still, he cautioned patience, pointing out that it took the United States two hundred years to build democracy.

After a long, almost bleak view of the situation in Ukraine, Yevstratiy, still an active priest in Chernihiv, assumed a pastoral tone. “I hope that with God’s help and with people’s cooperation who are wise and smart, we will learn lessons from these challenges,” he concluded.

Melinda Haring is the editor of the UkraineAlert at the Atlantic Council. She tweets @melindaharing. Vera Zimmerman interpreted the interview.

Image: Archbishop Zoria Yevstratiy, representative of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church Kyiv Patriarchate, gave an interview to UkraineAlert on October 26 in Washington, DC. Credit: Melinda Haring