It was nearly impossible to find an empty seat on the twice-weekly WizzAir flight from Berlin to Kutaisi this summer. The budget airline carries mostly German hikers to Georgia’s second largest city. From there, the hikers transfer in Zugdidi to reach their final destination, the remote and breathtaking Svaneti region, high in the Greater Caucasus. In Svaneti, most of these hikers undertake an established four-day hike from Mestia to Ushguli, one of the highest inhabited towns in Europe and home to striking UNESCO heritage sites. On the way, they stop overnight in three villages, which has boosted local economies.

It was nearly impossible to find an empty seat on the twice-weekly WizzAir flight from Berlin to Kutaisi this summer. The budget airline carries mostly German hikers to Georgia’s second largest city. From there, the hikers transfer in Zugdidi to reach their final destination, the remote and breathtaking Svaneti region, high in the Greater Caucasus. In Svaneti, most of these hikers undertake an established four-day hike from Mestia to Ushguli, one of the highest inhabited towns in Europe and home to striking UNESCO heritage sites. On the way, they stop overnight in three villages, which has boosted local economies.

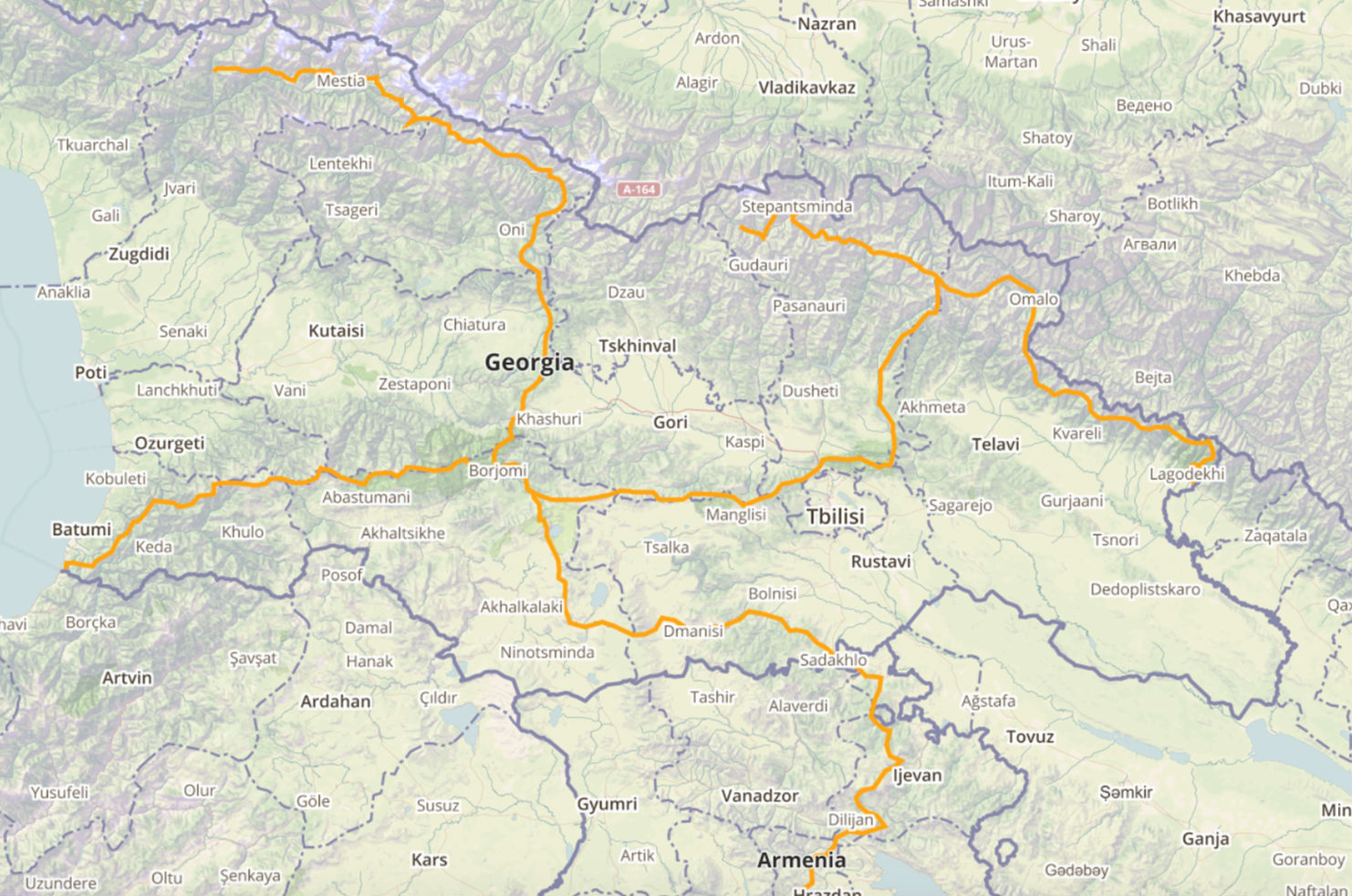

Inspired by the success of the Mestia-Ushguli route, a group of nature-loving idealists wants to elevate the Caucasus in hiking circles and bring world-class trails to other parts of Georgia, as well as to Armenia, Azerbaijan, and eventually, the conflict zones of South Ossetia, Abkhazia, and Nagorno-Karabakh. The non-profit Transcaucasian Trail is part peace-building, part sustainable development and economic growth, part conservation, and part outdoor adventurism. It plans to build and upgrade 1,800 miles of long-distance hiking trails out of existing overgrown trail routes from the Iranian-Armenian border through Georgia and from Georgia into Azerbaijan. Local and international volunteers are key to the development of the project. The trails are being built using internationally recognized methods, improving trail safety, and minimizing the need for routine maintenance as much as possible.

The nonprofit organization Transcaucasian Trail plans to build and upgrade 1,800 miles of hiking trails in the South Caucasus. Credit: Transcaucasian Trail

This audacious project isn’t simple to execute. The short-term challenges are physical and informational; trails will need to be built and cleared by hand, and maps of the area are difficult to find and often inaccurate. Soviet-era maps are the best and most detailed but out of date. Google Maps and open source material is often not detailed or reliable enough for hikers. Hikers who attempt to use these maps will find that it is easy to get lost by going off of the trail onto a cow path that then dead ends. Or they may find the existing trails washed out or thickly overgrown and impassable. Eventually, data on trail difficulty, lengths of hikes, elevation, and sites of notable interest will be avalable.

International volunteers help dig trail in Georgia during the summer of 2017. Credit: Laura Mills.

In Georgia, three volunteers rest on a trail in the Greater Caucasus range during the 2017 summer. Credit: Laura Linderman.

Completion of the Transcaucasian Trail depends on coordination and input from local NGOs and potentially government partners in three nations and three protracted conflict areas. Coordinating this effort and navigating closed borders and recent pain is not simple. But the benefits are tangible: groups that haven’t been able to easily meet will begin to create a system of sustainable trails and jobs that may contribute to peace. The trail literally connects different communities, and connects people figuratively through shared experiences and better understanding.

The benefits are numerous. Leaders of the trail movement hope to encourage free passage of diverse groups fragmented by conflict, Kremlin interference, and the legacy of Soviet policies. Trail sustainability initiatives and community-directed tourism may mean jobs in trail maintenance and other areas in these far-flung regions, reversing or reducing depopulation. Increased population alongside targeted public policies could revitalize minority languages in danger of dying out. Environmental activism has deep roots in the region but more work and resources are needed to increase and improve skills, programs, and long-term planning for sustainable trail maintenance. Policies that promote and protect natural resources are also needed, such as education on the danger of overharvesting endangered plant species. Finally, widespread love and enthusiasm for outdoor recreation needs to be matched by safe and environmentally sound access.

On the five hour minibus ride from Kutaisi to Mestia, the German hikers encountered native speakers of at least three mutually unintelligible languages, Georgian, Mingrelian, and Svan. The mountainous geography of the South Caucasus lends itself to ethnic and linguistic diversity, boasting the greatest density of distinct languages in the world. This diversity can and has lent itself to political regionalism and local autonomy. For example, until the building of a modern road into the region, Svaneti was only tenuously linked to Tbilisi’s central authority.

Despite the ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity, people have been interconnected in this region for years. Isolation and an inability to move freely prevents conflicts from moving out of a simmering, insecure, stasis. Building the trail across these borders could spur creative approaches to rethinking these conflicts. In 2018, Abkhaz and Georgian volunteers plan to lay trail in Armenia with international and local volunteers, which may give ordinary people space to have difficult but important conversations and form unlikely friendships.

Let’s hope that this remarkable project, of which I was proud to volunteer during the summer of 2017, succeeds. In addition to the benefits it will bring to the South Caucasus, it may provide an example for other areas hardened by conflict in the former Soviet Union, in eastern Ukraine and Crimea, and Transnistria in Moldova.

The Transcaucasian Trail invites international volunteers to lay trail in 2018. Perhaps I’ll see you there.

Laura Linderman is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Hikers explore the newly created section of the Transcaucasian Trail from Parz Lake to Gosh Lake in Armenia September 18. Credit: Vahagn Vardumyan via The Transcaucasian Trail