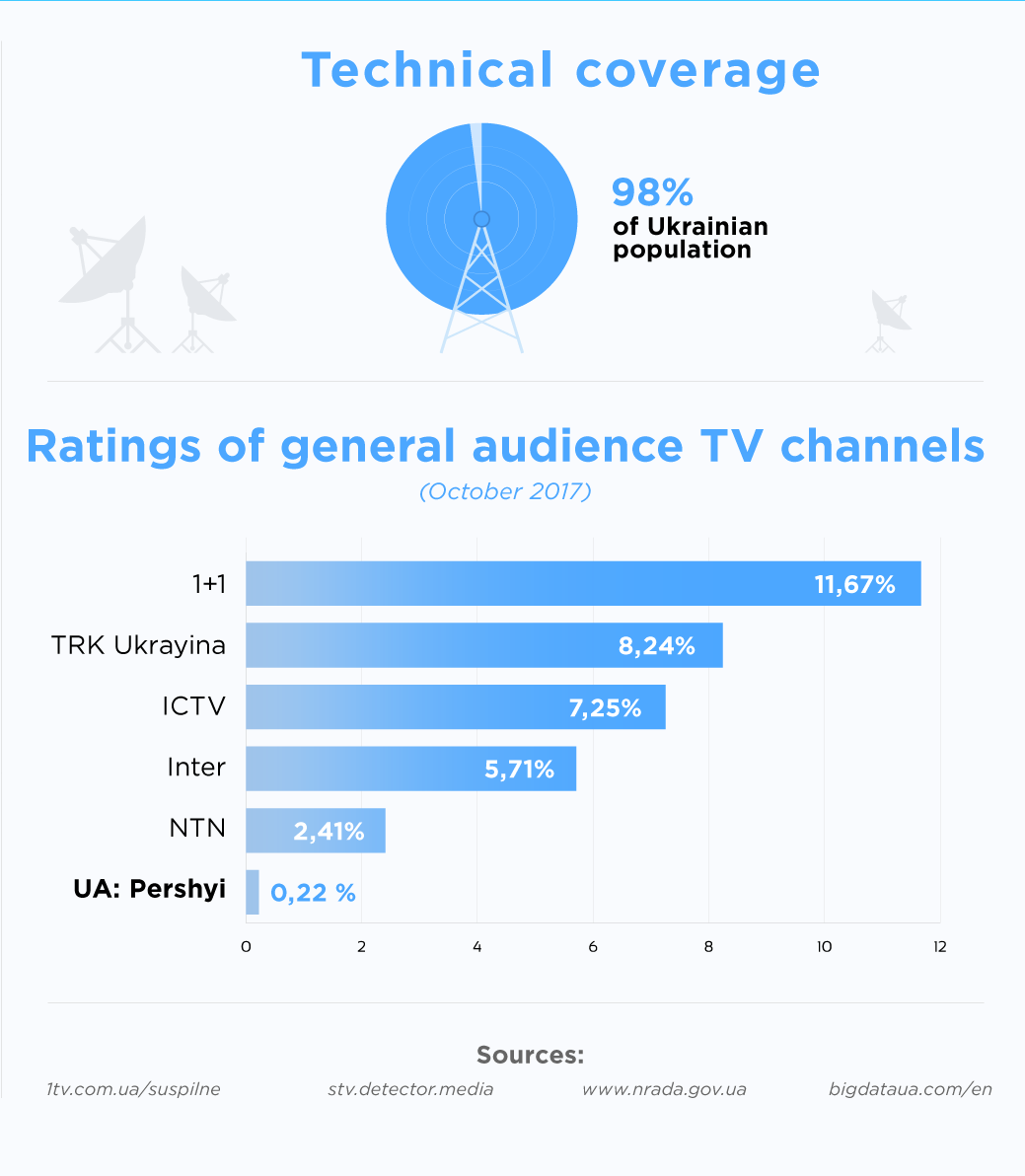

The oligarchs still control the airwaves in Ukraine. Ten of eleven national television channels are directly or indirectly connected to politicians and oligarchs. More than 75 percent of Ukrainians regularly watch TV channels owned by Ukrainian oligarchs Viktor Pinchuk, Ihor Kolomoisky, Dmytro Firtash, and Rinat Akhmetov. In radio, the situation is even worse: the top four radio groups (which also belong to oligarchs) reach 92 percent of the market. It’s easy to see why Ukraine needs an independent public broadcaster.

The oligarchs still control the airwaves in Ukraine. Ten of eleven national television channels are directly or indirectly connected to politicians and oligarchs. More than 75 percent of Ukrainians regularly watch TV channels owned by Ukrainian oligarchs Viktor Pinchuk, Ihor Kolomoisky, Dmytro Firtash, and Rinat Akhmetov. In radio, the situation is even worse: the top four radio groups (which also belong to oligarchs) reach 92 percent of the market. It’s easy to see why Ukraine needs an independent public broadcaster.

There’s an effort underway to put one in place. While the government has adopted legislation to create the first-ever public broadcaster, it has encountered numerous problems, namely funding and independence.

A number of top diplomats have taken notice, and have urged the government to properly finance Suspilne, the public broadcaster. Ambassadors from twenty countries, including Canada, France, Germany, the United States, and United Kingdom, plus the EU representative office and the NATO Liaison Office, have signed on. The European Broadcasting Union and the Council of Europe also support full funding.

A late newcomer

Historically, Ukraine’s state-owned media was fully dependent on government funding and its assets were disconnected. More than thirty state-owned TV channels and radio stations across the country had limited cooperation, no common development strategy, and were financed separately. The debate surrounding the creation of a public broadcaster has been ongoing since 1997, but the situation only began to change after 2014.

In April 2014 Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada set the ground rules for the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Company, which is responsible for reorganizing state-owned media into a united broadcaster. First National, the state-owned channel, officially acquired the status of public broadcaster in April 2015 and has been transformed into UA:Pershyi. By the end of 2015, all regional state-owned TV channels were merged with UA:Pershyi to form the all-Ukrainian public broadcaster. Other media products under the regulation of the State Committee in Television and Radio-Broadcasting of Ukraine, such as the National Radio Company of Ukraine, Ukrainian Radio, Ukrainian Studio of Television Films Ukrtelefilm, as well as the State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company Culture, have also become part of Suspilne.

This fact is very important—all state-owned companies producing media content were united into a single system with transparent funding and a single management team. The revamped National Public Broadcasting Company of Ukraine was officially created on January 19, 2017.

The people vs. oligarchs

Suspilne has two purposes: to inform and to set the rules of the game. Yevhen Hlibovytsky, a member of Suspilne’s supervisory board, thinks the public broadcaster will inevitably influence the entire media field, including commercial media, when launched in full.

However, the independence of the public broadcaster is essential, and there are still no guarantees that it will remain independent. The company’s management has studied the experience of public broadcasters in other countries where their independence has been compromised and used these findings during the preparation of its development strategy. Nevertheless, Suspilne faces huge risks of losing its embryonic independence.

Political brakes

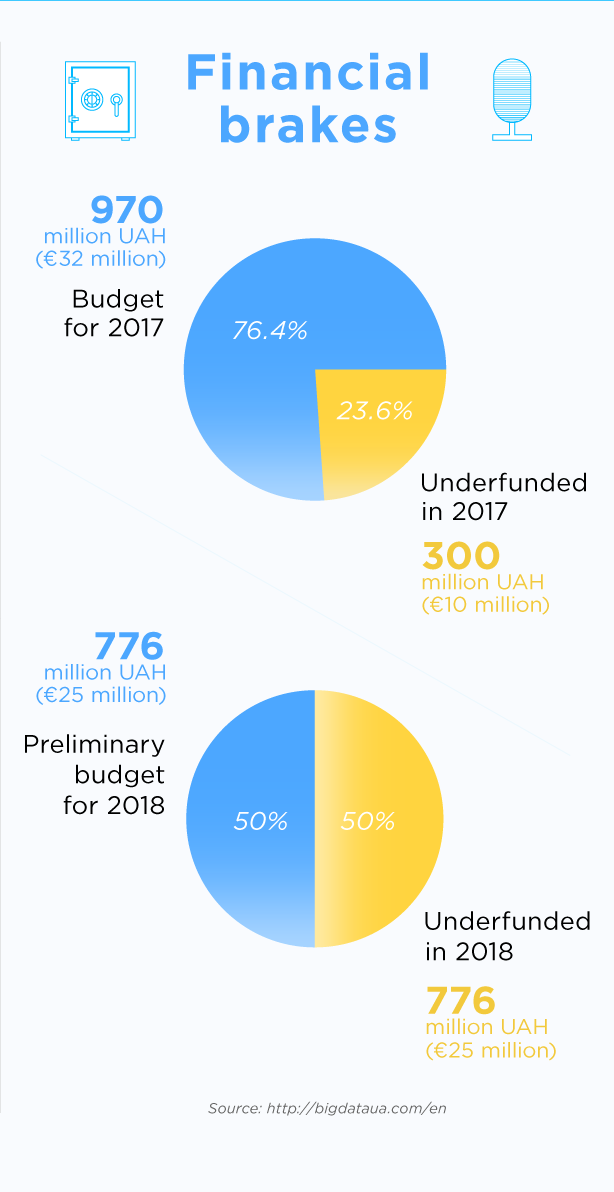

Suspilne is underfunded. According to the law on public broadcasting, Suspilne should get 0.2 percent of the state budget annually. In 2017, it should have received 1.2 billion hryvnias (40 million euros), but the Cabinet of Ministers allocated only 970 million hryvnias (32 million euros). High inflation at 14.6 percent also eats into the broadcaster’s miniscule budget.

This is one of the lowest budgets for a public broadcaster in Europe. For instance, Britain’s BBC has an annual budget of 4 billion pounds, while German public broadcaster ARD operates on 6.9 billion euro annually. These companies, however, benefit from a monthly fee each household has to pay, while Suspilne is totally dependent on the state.

It’s a shame because Suspilne is ready to revamp its programming. Daria Yurovska at Suspilne told me that the company wants to rework UA:Kultura, the culture-related TV channel, and invest in radio. Yurovska has also promised new television formats. One of them, the “Chereshchur” late night show, was launched in November 2017. But these plans have been endangered by budget cuts.

The worst part is that the government wants to give the broadcaster even less in 2018. According to the 2018 state budget, the Cabinet of Ministers and the Verkhovna Rada allocated 776 million hryvnias (nearly 25 million euros), while the law on public broadcasting sets Suspilne’s budget at 1,535 billion hryvnias in 2018.

Prime Minister Volodymyr Groisman stressed that 776 million hryvnias is “quite a lot,” but promised to allocate additional funds in 2018. Hlibovytsky suspects that the authorities have cut the budget intentionally in order to stop the development of Suspilne. “The lack of proper financing will not enable Suspilne to present itself to society as a successful reform. The coalition in the Verkhovna Rada is destroying trust toward Suspilne as a reform, hoping that it will not be able to transform itself into a full-scale public broadcaster,” he said.

Suspilne’s Yurovska agrees. A budget of 776 million does not give Suspilne any space for development. “This money will be enough only to cover real estate costs in Kyiv and the regions, and pay minimal salaries and expenses for broadcasting. There will be no money for the production of content—the main goal of Suspilne—or for modernisation of equipment. We will only have stagnation instead of progress,” Yurovska said.

Looking ahead, the biggest challenge is that ordinary people may lose trust in the nation’s first public broadcaster even before it is fully launched. The low ratings of UA:Pershyi at less than 1 percent demonstrate that the public will only pay attention to Suspilne when it becomes a true alternative to the current offerings. Unfortunately, the government’s moves all but ensure that this alternative voice may never get a chance to truly compete.

Vitalii Rybak is an analyst at Internews Ukraine and UkraineWorld.

Image: Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash arrives at court in Vienna, Austria, February 21, 2017. REUTERS/Heinz-Peter Bader