Data gaps, siloed thinking, the Global Food Crisis, and what we can do

Executive Summary

We currently face a complex global food crisis, driven by COVID-19, locusts, natural hazard and a global recession. Plummeting humanitarian funding, remittances and trade may exacerbate an already dire economic situation.

Data and modelling gaps exist at both micro and macro levels, across epidemiological predictions, economic impacts of COVID-19, agricultural yields and weather, amongst other factors.

Smartphones, featurephones, contained multiple MEMS, and IOT devices can be used to better collect data, Blockchain or Distributed Hash Table technologies can be used to verify data and Next-generation satellite networks in low Earth orbit and mesh networks can be used to share data.

Siloed thinking is widespread, with private sector often uninvolved with humanitarian response. Greater awareness of risks and impacts may attract ESG money from the finance sector and the agriculture industry can be critical both as a source of data and as a data dissemination network.

Introduction

Populations around the world face an unprecedented, complex, and multifaceted global food crisis. As outlined in an earlier article, a variety of drivers fuel this crisis, including COVID-19, natural hazards, locusts, lockdowns, and a global recession.

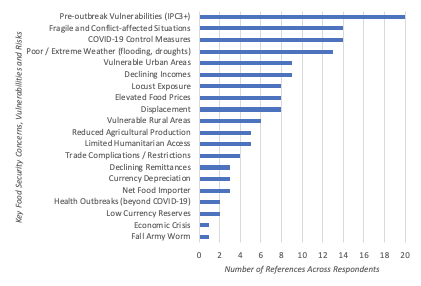

The diagram below shows key food security concerns, vulnerabilities, and risks identified by the World Bank’s Famine Action Mechanism (FAM) partners.

Context

Despite a bumper crop harvest in several regions of the world and successful locust control operations in Southwest Asia, the crisis remains stark, emphasized in the recent OXFAM publication, Later will be too late.

Alarmingly, the OXFAM publication reports that as of the end of September 2020, donors have provided just 28% ($2.85 billion) of the $10.19 billion requested in the UN Global Humanitarian Response Plan for COVID-19. Breaking that figure down by sector, it falls to 10.6% for food security ($254.4 million provided out of $2.4 billion requested), and to a paltry 3.2% for nutrition ($7.9 million provided out of $247.8 million requested).

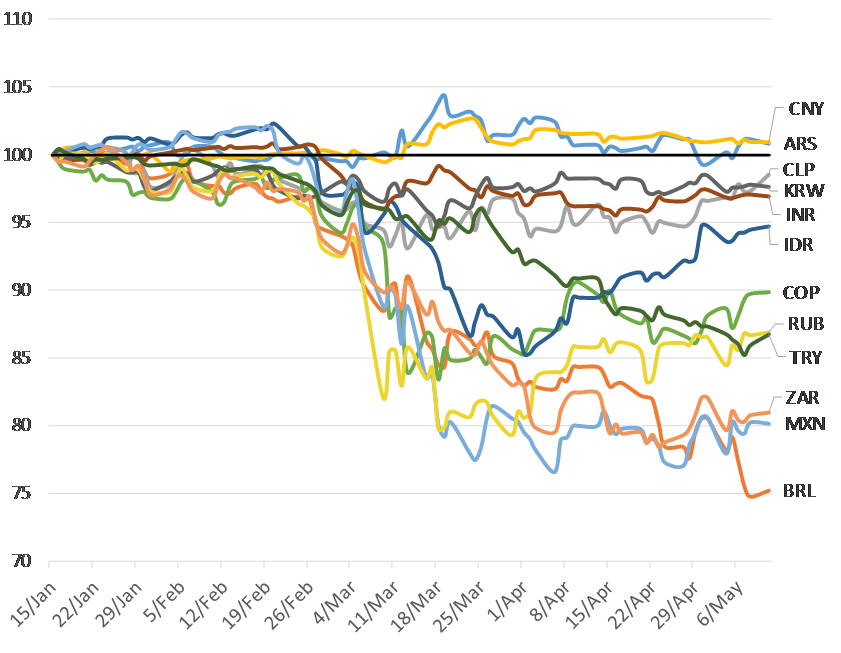

This gap in humanitarian aid funding is matched by equally concerning economic indicators. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) produced a trade and development report that predicts a fall in remittances of $100 billion in 2020, and sharp currency devaluations have been seen across emerging market economies and sub-Saharan Africa.

The currency devaluations coincide with the ballooning sovereign debt crisis, with Zambia on the verge of default. This has led to a widespread drop in food access, with many people unable to afford to purchase food. Although global food prices remain stable, a potential US-China trade war could spark off a protectionist frenzy and a possible repeat of 2007/8, when trade restrictions contributed to global food price spikes. Finally, limitations in farmer credit and concerns about market access to sell crops may have both contributed to lower levels of planting in several countries around the globe.

Data gaps

Due to a lack of available data, it is extremely challenging to make data-driven decisions in this domain, a constraint faced by political, financial, humanitarian, and other actors. Filling data gaps could lead to a more widespread and improved response.

Macro and micro decisions

Macro and micro decisions

Macro decisions are made by a wide range of actors, with national-level policy enacted by critical stakeholders including treasuries, agricultural ministries, and transport ministries. These critical stakeholders are supported by the donor community, including aid agencies and multilateral development banks.

Finally, the role of the private sector shouldn’t be ignored: large agricultural companies and agricultural banks play important roles in ensuring that farmer livelihoods are preserved and that supply chains continue to function.

Macro-level constraints: data and modeling gaps

Macro actors are often highly time constrained, and are further constrained by a lack of readily available relevant data and analysis, and a lack of ability to quickly find and retrieve it.

There are several macro-level data and modelling gaps, including the following:

Epidemiological modelling: This increases the ability to predict the number of COVID-19 cases over time, both nationally and regionally, under different control policy responses.

Exceptional efforts to improve epidemiological modelling include Mitigation Calculator; an increased ability to predict cases and policy responses will give farmers increased certainty of market access and may encourage planting.

Economic modelling: This focuses on the potential economic impacts of lockdown measures; decreased trade, foreign direct investment, aid, remittances, and currency depreciations can lead to loss of food access.

Being able to predict these effects through economic modelling can help ensure that the necessary social protection measures are put in place to increase food access.

Food price modelling: Local food prices have been volatile with COVID-19 control measures, and international prices can affect both foreign currency reserves and the balance of payments position. Impacts on both local and international prices could affect food access.

Yield and output modelling: Supply chain disruption due to lockdowns has meant that seeds, fertilizer, and agrochemicals couldn’t be distributed, and seasonal workers weren’t able to travel. A lack of capital for farmers, combined with concerns about market access, may have led to decreased levels of planting. Monitoring harvests informs potential future food availability issues.

Trade data and modelling: Trade isolationism and protectionist policies have proliferated with the rise of populism and nationalism driven by national-level COVID-19 responses. Food importers run the risk of a loss of food availability if there are escalating restrictions. Modelling the impact of different trade scenarios can ensure the necessary contingency measures are put in place.

Micro decisions

Micro decisions are made by a wide range of actors, including farmers, farming cooperatives, local agricultural banks, and micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). These actors work across the food supply chain, in planting, harvesting, storage, and distribution.

Micro-level constraints: data and modeling gaps

Weather data, soil moisture, and plant health: Improved data on weather modelling, predicted soil moisture levels, and plant health informs yield and output predictions

Local market price predictions: Local market price predictions and market access affect farmer confidence and planting levels. More accurate predictions may increase confidence.

Farmer access to credit: With the uncertainty of the economic impacts of COVID-19, there is greater uncertainty on the future of agricultural banks, lending levels, and lending criteria.

Localized epidemiological data: Hyper-localized epidemiological data could help predict both labour shortages and potential closing of markets.

How can this be better sourced, collated and disseminated?

Technology can be used to better collect data. Smartphones & Featurephones contained multiple MEMS (microelectromechanical systems) sensors, such as accelerometers and temperature sensors are examples. This data can be analysed and aggregated to gather insights into the ambient environment, as well as an impression of social interactions, mood, intoxication, etc.

Cheap IOT sensor/actuators that use varying contact metal strips, the movement of which can be detected with Wi-Fi backscattering analysis on commercial off-the-shelf wireless routing technology are another example. This enables anything that is moved or opened (such as a pill container, or even fluid flowing through a bottle) to communicate with the cloud.

Blockchain or Distributed Hash Table technologies can be applied to create indelible public records, thereby ensuring trust less data integrity, and avoiding the dangers of a sensor being manipulated adversely, ensuring verification of the data.

Sharing Data & Ensuring Safety

Next-generation satellite networks in low Earth orbit (e.g. Starlink) enable high-bandwidth low-latency connections even in areas traditionally underserved by communications infrastructure. Mesh networks enable the communication of information between devices in a dynamic peer-to-peer manner. Thus can extend communication links far beyond the nearest endpoint of a hard network.

Encryption techniques such as zero knowledge proofs, homomorphic encryption and differential privacy respectively enable:

- Proof that someone has access or ownership rights to something without divulging the specifics characteristics of it.

- Machine learning activities to be performed on fully-encrypted data.

- the aggregation of a number of different data elements into one large blend, greatly diminishing the risk of an individual’s activities being detected, yet retaining the utility of using their data.

Models can be used for improved decision making through the following. Predictive machine learning processes can assist stakeholders in making the most of available resources by anticipating demand in advance, to enable better fulfilment, mitigating problems whilst they are still small before they become more problematic, being better able to seize emerging opportunities and protecting against fraud or adulteration.

Siloed thinking

Because the global food crisis is a multi-faceted and multi-disciplinary problem, it requires cooperation, along with data sharing. Although some collaborative groups exist, membership typically comprises UN agencies and/or local or international NGOs, with little government or private sector involvement. This distance due to bureaucracy can make it harder to maintain interfaces with the general public, and does not serve interaction between communities. Innovations may therefore face challenges in diffusing due to a lack of exposure, or a lack of translation into local cultures and contexts.

The potential role of the financial sector

Environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) financial flows have increased in recent years, with a particular focus on climate change, and subsequently agriculture. The costs of food insecurity and malnutrition are widespread and diverse, including loss of productivity, loss of farmer livelihoods, civil unrest, and economic and political instability. The effects of malnutrition on mental and physical wellbeing may last a lifetime.

Smart investments aiming to maintain food security can also contribute to maintaining portfolio performance across sectors. Investments in food systems that are resilient to pandemics, climate change, and other natural and non-natural hazards are a long bet, but will likely enable major returns in terms of capital and societal value in the long run. Investment into these the development and scaling of these technologies may need to come from public sources as it may be a challenge to convince venture capital of a sufficiently fast return.

The potential role of the agricultural sector

Local agricultural industry is the primary source of on-the-ground data. If data can be sourced from farmers, farm technology, and cooperatives, it can help inform both other micro- and macro-level decision makers, ultimately helping them make decisions that benefit farmers. Aggregation of data can also enable new forms of multi-sided markets, whilst removing opportunities for rent-seeking through informational arbitrage. Middlemen can be removed, enabled peer-to-peer commerce, such as the trade and rental of farm equipment, or livestock for animal husbandry purposes, as well. This may provide ancillary income for farmers, as well as second order effects such as enabling stronger cohesion within society.

Such networks can also diffuse information about the relative pricing of produce in different areas. This can reduce the risk of famine by illustrating opportunities to distribute food to other areas where it is rare (and therefore expensive) thereby gaining a higher price.

The Food Systems Handbook

The Food Systems Handbook is an open-source, community-run project championed by AC GeoTech Fellow Sahil Shah and designed to collate and categorize information on the current global food crisis. The team is running a series of round-tables this October 30/31 to convene experts to discuss data gaps and solving siloed thinking in the current crisis, and you can sign up to be part of them here.

Image: "Drone Photography - Aerial Farm" by JamesBastable