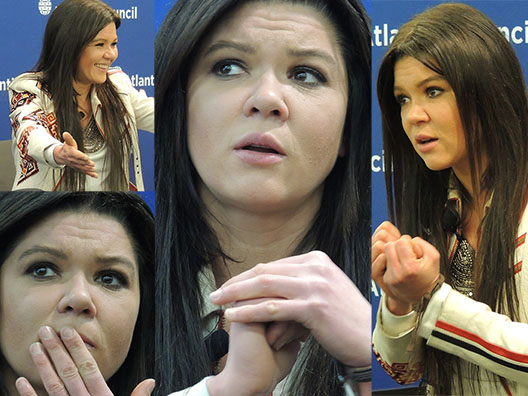

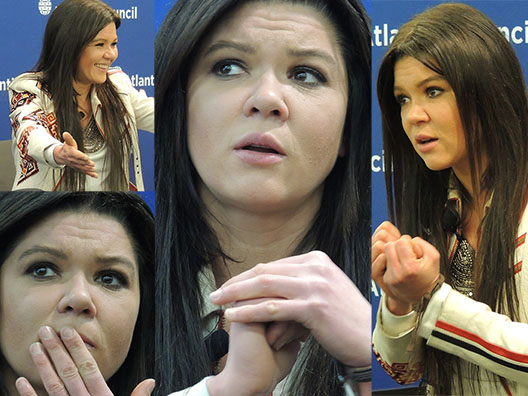

Ukrainian pop music star and political activist Ruslana Lyzhychko swept her long, straight hair back from her face and leaned forward, hands folded, on a podium at the Atlantic Council. In the passionate alto that has electrified concert audiences worldwide, she pleaded quietly in English to a crowded room: “Don’t do something, do everything – to keep peace [in Ukraine] … before Putin will kill us.”

Ukrainian pop music star and political activist Ruslana Lyzhychko swept her long, straight hair back from her face and leaned forward, hands folded, on a podium at the Atlantic Council. In the passionate alto that has electrified concert audiences worldwide, she pleaded quietly in English to a crowded room: “Don’t do something, do everything – to keep peace [in Ukraine] … before Putin will kill us.”

Ruslana – known to the music and political worlds by her first name – called for strong US and European support for Ukraine against Russian President Vladimir Putin, and for steps to halt Russia’s seizure of Ukraine’s Crimea region. In a week of Ukraine policy debates and panel discussions among diplomats, policymakers and scholars in this city, what Ruslana brought was passion – nationalist and democratic.

For much of the past four months of massive protests at Kyiv’s Maidan, or central square, Ruslana’s voice has boomed in Ukrainian from loudspeakers on the stage. As protesters confronted and overthrew Ukraine’s corrupt, Russian-aligned president, Viktor Yanukovych, Ruslana helped energize that movement with songs and speeches. And in Yanukoych’s final days, when phalanxes of police loyal to him attacked the crowd, she called from the stage for calm and non-violence.

This week, in Washington to receive the State Department’s Women of Courage award, she is speaking instead to foreigners. “My duty is to pass on to you the message of the Ukrainian people,” she said. Between meetings – at the White House with Vice President Biden and at Capitol Hill with Senator John McCain – she is regularly on the phone, “with my friends from Crimea, from Ukraine; I check the information all the time.”

Talking with audience members, Ruslana jumped up from her chair to evoke Ukrainian protesters standing erect before police forces that included snipers who killed many of the more than 80 people who died amid Yanukovych’s ouster. “I have seen those who were murdered … and I don’t want to see any more people killed, she said. “It’s impossible to sleep at night if you know that you could have done something and yet you didn’t do it.”

Ruslana was born in Ukraine’s far west, where pro-European and anti-Russian sentiments are strong, and writes much of her music from her roots in the folk music of western Ukraine’s Carpathian Mountain region. But in a country with a deep historical divide of east from west, she underscores the multi-ethnic impulse of the Maidan revolt that she helps to personify. “Do you know who was murdered on Maidan?” she asked the room. “They were Ukrainians from all parts of Ukraine … students, farmers, workers. There was an ethnic Belarusan, an ethnic Armenian, there were Jews, people of all nationalities living in Ukraine. … Today I had a call from Crimean Tatars who said told me, ‘We know that we will be the first to be killed” if new fighting breaks out in Crimea.

Ruslana underscored the danger that Russia’s deployment of troops into Ukraine will lead to war. To prevent that, and to block a permanent Russian takeover of Crimea, “we ask for three things” from the international community, she said. “Block [Putin’s] money and we will block the war,” she said, urging financial sanctions on “Russian bad guys who organize this.” She also called for efforts to avert “this un-legal referendum in Crimea” that the pro-Russian regional authorities, backed by Russian troops have scheduled for next week to seek independence. Third, she asked for “a peacekeeping mission to go to Crimea right now.”

Asked about the ability of Ukraine’s deeply fractured political parties to unite on a strong government to oppose Russia and deal with the country’s financial and other crises, Ruslana suggested that Russia’s intervention in Ukraine has had a unifying effect. “Maybe people outside of Ukraine are seeing a political conflict” internally, she said. “But we don’t care which political parties they [the new government ministers] are representing, as long as there are no representatives of Putin there.”