Think of defense contracting in four distinct market types.

Several recent headlines—

- “Senators Call For Oversight On LRS-B Cost Estimates”

- “Oshkosh Wins JLTV Award”

- “Kendall ‘Open-Minded’ On Sharing RD-180 Replacement Costs”

- “Can Secretary Carter win over Silicon Valley?”

—got me thinking about menswear and defense acquisition and why they are both so persistently difficult. It’s the maddening variety of segments! If weapons were three-piece suits, the difficulty would be akin to the challenge of shopping smartly from Savile Row to Sears while still scoring points on fashionista.com.

Navigating such diverse markets without getting taken to the cleaners requires careful discernment of means and ends, one’s own and those of the vendors. There is arguably good value in a single pair of trousers costing $20, $200, or $2,000, after all, but you need to know what you’re doing. Most importantly, you need to know how to make material distinctions.

So too in defense acquisition. For our militaries’ better buyers, the obverse of Michael Porter’s catechism for a firm’s competitive advantage is equally instructive: Figure out how to exploit the particular dynamics of competition each program opportunity will activate, and you can buy the weapon with greater efficiency and productivity.

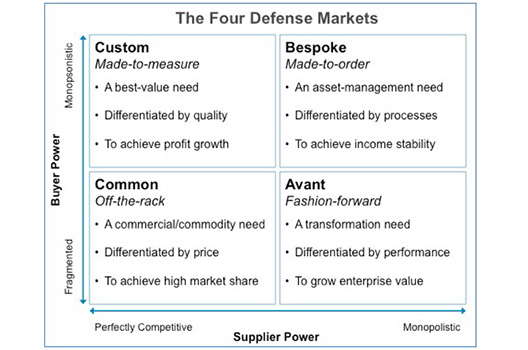

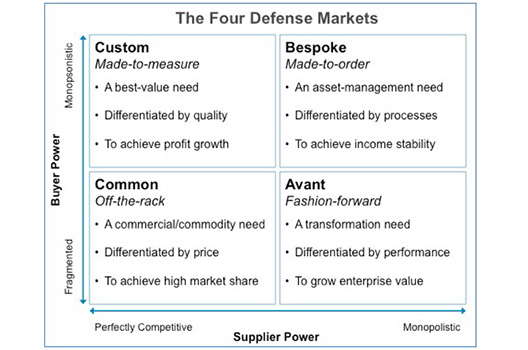

Accordingly, smart acquisition requires understanding the power dynamics in the structure of the market. And although program acquisition strategies address a multitude of product markets—strategic aircraft, armored trucks, and rocket propulsion, among them—a coarse summary of all their power dynamics suggests four meta-markets that can facilitate the making of distinctions in defense acquisition. Each of these four defense “markets” is characterized by the type of need it transacts, the form of differentiation that matters most in it, and the financial measure that shapes supplier incentives, as illustrated:

- Bespoke. A Bespoke market is where ministries procure their most exquisite, capital-intensive industrial capabilities from a concentrated caste of franchise holders. The Long Range Strike Bomber program exemplifies such a dreamcoat of an industrial capability for aircraft. Like Savile Row, this is a gentlemanly marketplace of quiet extravagance paced to a clockspeed of generations and fueled by the costly privilege of buyers’ obsessive control over it.

- Custom. A Custom market is where ministries find the preponderance of their weapon systems for sale by a small but rivalrous band of competitors. The Joint Light Tactical Vehicle program exemplifies the needs that get transacted in this made-to-measure market. Because of the power asymmetry that defines it and the profit-growth imperative on its suppliers, Custom is a contentious marketplace where buyers demand good value and the vendors generally are feeling the squeeze.

- Common. A Common market is where ministries go bargain hunting to access the scale efficiencies their otherwise rarified needs don’t make possible. By slightly amplifying Under Secretary Kendall’s remarks about how the Pentagon may acquire a new boost-stage rocket engine, the market’s proletarian appeal comes clear: “Rather than just paying for new engine development [in the Custom or Bespoke markets], the approach we would prefer is to help someone close their business case for providing launch services [so that we can later buy a launch in the Common market at lower total cost].” Of course, this is a raucous bazaar of a marketplace for the staid defense buyer, and to participate effectively he must gain confidence in the discipline of the clamor to drive low prices with acceptable quality.

- Avant. An Avant market is where defense customers go to find a cutting-edge transformation of their capabilities. However, on these runways the market-power asymmetry is tilted against the ministry, and suppliers are amenable to only so much control as investment capital will buy them. This is why Secretary Carter’s trip to Silicon Valley last month was punctuated by announcement of the Pentagon’s $75 million investment in a public-private venture to develop flexible electronics.

As it happens, most contemporary approaches to improving acquisition management recognize the importance of distinguishing among the different segments from which ministries can acquire their goods and services. One point of emphasis in Better Buying Power, the signature acquisition initiative of the Obama-era Pentagon, is the need to match contract types and profit rates to the market context and objectives of a given procurement. Similarly, it is an appreciation of the importance to the Pentagon of its access to more non-traditional segments that underlies provisions in the US Senate’s 2016 defense authorization bill that would create new “pathways” to the commercial sector. “Accessing sources of innovation beyond the Department is critical for national security in the future, especially in areas such as cyber security, robotics, data analytics, miniaturization, and autonomy,” reads the Committee’s overview of those provisions.

The Pentagon says its investment in flexible electronics, for instance, will advance “new techniques in electronic device handling and high precision printing on flexible, stretchable substrates… [enabling new products from] wearable devices to improved medical health monitoring technologies.”

So, apparently a weapon system may yet be a three-piece suit.

Steve Grundman is the M.A. and George Lund Fellow for Emerging Defense Challenges at the Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security. This article first appeared in the 2 September edition of Aviation Week & Space Technology as “Apply ‘Bazaar’ Approach To Procurement”.