Consuming 40 percent of the Pentagon’s future spending plans, the JSF may come to dominate defense planning

Earlier this week, Australian Prime Minster Tony Abbot announced that the Royal Australian Air Force’s order for F-35A Lightning IIs was now up to a full wing of 72 aircraft. The bad news is that each aircraft, even deducting for infrastructural expenses in Australia, will cost $173 million (US). The planned capabilities of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) aside, that’s rather above the going rate for a fighter jet today. Thus, as Bloomberg and Politico Morning Defense reported, “that total represents a decline from Australia’s 2009 plan to buy 100 of the fighters… in the latest sign that cost overruns and tightening defense budgets are forcing countries to think twice about ordering more F-35s.”

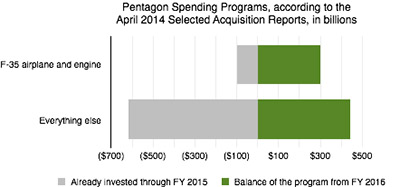

In the US, though, the approach so far has been to raid other lines to pay the higher costs, and the forward-looking results are stark. Atlantic Council member Byron Callan, who is also director of defense industry analysis at Capital Alpha Partners, recently published a research note on the latest data (17 April) in the US Defense Department’s Selected Acquisition Reports. Taking the liberty of condensing his main chart, I have arranged all the programs into two categories: the F-35, and everything else. The graph below shows just how thoroughly the Pentagon is betting the farm on the JSF.

This may seem unreal, perhaps because monies sunk so far across the defense program have not been so heavily weighted towards the F-35. Investment in the plane has to date totaled 14 percent of the sunk costs in all SAR programs. And admittedly, the figures do not include the Army’s forthcoming Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicles, the Navy’s planned replacement for the Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, the Air Force’s hoped-for Long Range Strike Bombers, any unforeseen future programs, any currently classified programs, or a host of minor programs not subject to a SAR. All the same, the F-35 accounts for just over 40 percent of all openly planned spending on major programs after 2015.

Fourteen percent to forty percent makes for a big jump. Consequently, that airplane, its engine, and its contractors may soon dominate military-industrial planning in the United States. Consider that while the F-35 is a large part of Lockheed Martin, it’s far from the whole company. It’s thus worth asking whether Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney may come to control over half the value of military prime contracts in the US. Could Lockheed Martin become the United States’ national champion in military production, rather like BAE Systems in the United Kingdom? Would that status bring the same problematic relationship? Just how far would the US government go to protect its interests in this enterprise?

James Hasik is a senior fellow in the Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security.