European Union leaders sat down this week in Brussels for a summit with a China it recently branded a “systemic rival,” and the United States is nearing the end game of trade talks with a China that national security documents refer to as a “strategic adversary.”

So, it’s surprising that transatlantic leaders are neither working at common cause nor asking the most crucial geopolitical questions of our age.

What sort of world does China want to create?

With what means would it achieve its aims?

And, what should the United States and Europe do to influence the outcome?

By now, there is little remaining doubt that China’s continued rise marks the most significant geopolitical event shaping the 21st century. Yet US and European officials – mired in issues ranging from Trump administration immigration gyrations to Brexit – have failed to give this mother of all inflection points enough attention.

Some are in denial about the fundamental change China’s rise may bring to the global order of institutions and principles established by the United States and its allies after World War II. Others concede that the structural stress between a rising China and an incumbent United States is the defining danger of our times, yet they offer neither an engagement or containment strategy worthy of this epochal challenge.

That has produced the worst of all worlds.

Fearful that the United States has grown more determined to undermine his country’s rise, President Xi has doubled down on his determination to strengthen the Communist party’s hold domestically while advancing China’s global influence. European allies – stung by trade actions against them and the lack of a US galvanizing strategy to China – are hedging their bets.

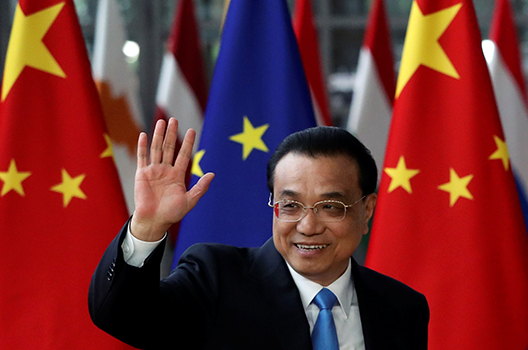

European Council President Donald Tusk declared a “breakthrough” this week on some of the EU’s major trade disagreements, particularly regarding tech transfers and industrial state subsidies. Then in Croatia a couple of days later, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang pledged to respect EU standards and laws at a summit with Central and East European countries that closed 40 deals and expanded its ranks to Greece so that the so-called 16+1 grouping became 17+1.

That relatively positive news in Europe only further underscores the skill with which Chinese leaders are managing their historic aspirations.

Graham Allison, one of America’s most astute China watchers, quotes Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, who shortly before his death in 2015 said this: “The size of China’s displacement of the world balance is such that the world must find a new balance. It is not possible to pretend that this is just another big player. This is the biggest player in the history of the world.”

In that context, what China wants is a play in three acts.

First, China wants ideally to push the US out of its Asian region, or at the very least reduce its influence, to achieve a regional hegemony that makes all actors ultimately dependent on it. Second, it is acting globally to displace, if not yet replace, the United States wherever it can – including in major parts of Europe – most importantly through its Belt and Road Initiative.

Finally, it’s clearer than ever that Beijing by the time of the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China in 2049 aspires to be the dominant economic, political and perhaps military power for an era where democracies remain but authoritarian systems are ascendant.

“China is unabashedly undermining the U.S. alliance system in Asia,’” writes Oriana Skylar Mastro of Georgetown University in Foreign Affairs. “It has encouraged the Philippines to distance itself from the United States, it has supported South Korea’s efforts to take a softer line toward North Korea, and it has backed Japan’s stance against American protectionism…It is blatantly militarizing the South China Sea ….It is no longer content to play second fiddle to the United States and seeks directly to challenge its position in the Indo-Pacific region.”

Yet it is beyond Asia where China’s reach has expanded fastest.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the Belt and Road Initiative, whose impact on its times may outstrip that of America’s Marshall Plan, which at $13 billion of funding had neither the BRI’s global aspiration or resources. Launched only in 2013, conservative estimates have China already spending $400 billion on the BRI with hundreds of millions more in the pipeline for projects with some 86 countries and international organizations, most recently including the first G-7 member, Italy.

Though the BRI is a development scheme, its political and security benefits for China grow increasingly clear, whether through EU members who oppose human rights statements against Beijing or African or Middle Eastern countries who will be less likely over time to provide US forces military access.

Finally, a growing number of experts believe China on current trajectories wants to fill America’s shoes as the dominant global agenda-setter and rule-maker.

Write Bradley A. Thayer and John M. Friend, authors of the 2018 book How China Sees the World, “By 2040, Western-led institutions will remain, but their liberal principles will be diluted by reforms required by Beijing. As China’s economic power increases and more countries in both the developed and developing world become dependent on Chinese trade and investment, Beijing will use its economic statecraft to pressure countries to downplay or abandon their democratic values and liberal policies.”

By then, their relative resources will provide them far greater leverage.

If China reaches its stated development goals for the centennial of the Communist party in 2021, and then the centennial of the People’s Republic in 2049, it will be 40% larger than the US economy by the first date and be three times larger by the second! (measured by purchasing power parity)

With stakes that high, the secondary questions are crucial. Does Beijing have the wherewithal to achieve such lofty aims and can the US and Europe alter that trajectory?

The answer to both questions is yes, but….

Chinese leaders’ reawakened sense of destiny is a much more overpowering force than is generally understood in Washington. Financial markets and Western political capitals are littered with those who have underestimated the durability of China’s rise.

That said, China’s slowing economy, the loss of manufacturing jobs, and its increasingly autocratic system introduce new vulnerabilities. There’s a higher level of grumbling among its business elites, political class and foreign investors.

Given the choice, most countries in the world still would rather navigate a world order where the United States is the dominant actor rather than China.

For that to be an option, however, the US and Europe will have to change course in three respects.

First, they will have to address domestic challenges that have made their democratic and economic models less appealing globally. They will have to reinvigorate and, in some cases, reinvent the multilateral systems it and others created after World War II. Finally, they must find a way to act together to more intensively and more effectively engage with China to shape the future — collaborating with China where possible and competing where necessary.

As it’s now clear what China wants, a coordinated US and European response grows more urgent.

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com.

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe. Subscribe to his weekly InflectionPoints newsletter.

Image: Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang arrives at the European Council to meet European Institution leaders for the EU-China summit in Brussels, Belgium April 9, 2019. (REUTERS/Yves Herman)