Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev could hardly believe his good fortune.

He had known from his intelligence that Kennedy was planning some sort of Cuban operation aimed at unseating Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Yet never in his fondest dreams had he anticipated the incompetence of the botched Bay of Pigs invasion.

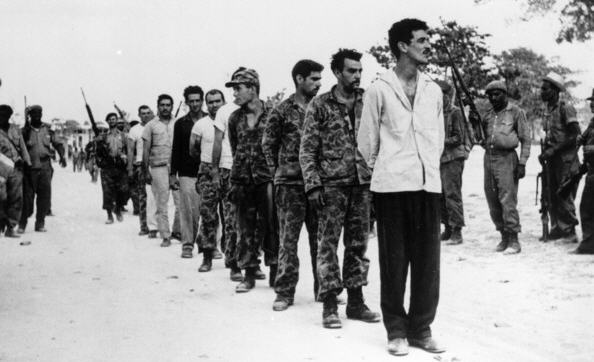

When it was all over, Castro had killed 114 of the CIA-backed exile force and had taken 1,189 prisoners. He had gained his enemies’ surrender after three days of fighting. Kennedy, by refusing the direct U.S. military involvement that might have ensured the action’s success, had avoided giving Khrushchev a pretext for a tit-for-tat response in the Berlin.

However, Kennedy’s fiasco at the same time provided the Soviet leader what he considered valuable new insight into the sort of man who was leading the U.S. “I don’t understand Kennedy,” Khrushchev said to his son Sergei at the time. “Can he really be that indecisive?” He compared the Bay of Pigs debacle unfavorably to his own bloody but bold intervention of Soviet troops in Hungary in 1956 to ensure that country remained firmly in the communist sphere of influence.

Best of all for Khrushchev, the most dramatic failure of Kennedy’s first weeks in office had coincided with one of Khrushchev’s most impressive historic achievements. Just a few days earlier on April 12, the Soviets had launched cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin as the first human in space and the first human to orbit the Earth. Khrushchev burst with joy, pride and relief.

Gagarin had provided him with the political booster rocket he so badly needed ahead of his October party conference. Combined with Kennedy’s botched Bay of Pigs invasion, the Soviet leader had gone further toward neutralizing his enemies in a single week than he ever could have imagined.

It had been six weeks since Khrushchev had met the U.S. ambassador in Siberia and relayed his reluctance to accept Kennedy’s invitation for a meeting. Now that Kennedy had been so weakened, Khrushchev was ready to accept. For all the perils of coming to the meeting without proper time for preparation and in a now-weakened position, Kennedy less than a month after the Bay of Pigs invasion would agree as well to the Vienna Summit.

Former Secretary of State Dean Acheson immediately grasped the potential negative impact Kennedy’s Cuba failure would have on Khrushchev’s thinking and on Allied confidence ahead of the summit. He considered it “a completely un-thought-out, irresponsible thing to do.” Speaking later before diplomats at the Foreign Service Institute, he said, “The European view was that we were watching a gifted young amateur practice with a boomerang, when they saw, to their horror, that he had knocked himself out.”

Acheson wrote to his former boss President Harry Truman: “The direction of this government seems surprisingly week,” he said. “So far as I can make out the mere inertia of the Eisenhower plan carried it to execution. All that the present administration did was take out of it those elements of strength essential to its success. Brains are no substitute for judgment. Kennedy has, abroad at least, lost a very large part of the almost fanatical admiration which his youth and good looks have inspired.”

In the space of just a few days in April, the script for the Berlin Crisis of 1961had been dramatically altered.

Fred Kempe is president and CEO of the Atlantic Council. His latest book, Berlin 1961, was published May 10. This blog series originally published by Reuters. Photo: A group of captured U.S.-backed Cuban exiles, known as Brigade 2506, being lined up by Fidel Castro’s soldiers at the Bahía de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs), Cuba, following an unsuccessful invasion of the island, April 1961. (Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Image: bay-of-pigs.jpg