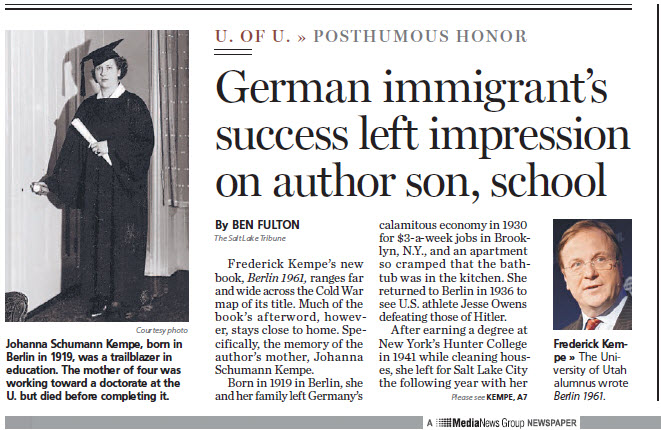

On its front page, the Salt Lake Tribune published a moving tribute to my late mother, Johanna Schumann Kempe, who was honored by the University of Utah’s College of Humanities as one of two distinguished alumni at Friday’s graduation ceremony. At a lunch in her honor a day earlier, Dean Robert Newman spoke of her as a pioneer.

"Immigrant’s success left impression on author son, school" – Ben Fulton, Salt Lake Tribune.

Frederick Kempe’s new book, Berlin 1961, ranges far and wide across the Cold War map of its title. Much of the book’s afterword, however, stays close to home. Specifically, the memory of the author’s mother, Johanna Schumann Kempe.

Born in 1919 in Berlin, she and her family left Germany’s calamitous economy in 1930 for $3-a-week jobs in Brooklyn, N.Y., and an apartment so cramped that the bathtub was in the kitchen. She returned to Berlin in 1936 to see U.S. athlete Jesse Owens defeating those of Hitler.

After earning a degree at New York’s Hunter College in 1941 while cleaning houses, she left for Salt Lake City the following year with her parents, who had converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She taught school, wrote plays and books for children and raised a family of four children with her husband, Fritz. But the city of her birth was never far from her heart.

"My association with Berlin began in the womb," Kempe writes in his book. "My mother insisted Berliners were more free-spirited and flexible than other Germans, and more witty and worldly."

To that description, Kempe, a Salt Lake City native and veteran journalist, could have added "determined."

Rather than retire after teaching at Canyon Rim Elementary School in Granite School District, Johanna Kempe embarked on graduate studies in German at the University of Utah’s College of Humanities. Upon earning a master’s degree in 1985 at age 66, she began work on a doctorate, with a dissertation on William Shakespeare’s influence on German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder.

She died unexpectedly in 1988, leaving her doctorate unfinished. But at U. graduation ceremonies, Johanna Kempe will be honored posthumously as a distinguished alumna of the U.’s College of Humanities, along with Hal Cannon, founder of the Western Folklife Center and the Elko, Nev.-based Cowboy Poetry Festival.

"In those days, it was not a given to see students of her age walking from class to class," said Gerhard Knapp, a retired U. professor of German and comparative literature, who was chairman of Johanna Kempe’s master’s committee. "She, unfortunately, felt the bias of some who didn’t appreciate her presence, but she was treasured in our little department. Her papers were always original and thoughtful."

After their mother’s death, Frederick and his three sisters established a memorial scholarship in the name of their parents. Given to a College of Humanities graduate student age 60 or older, the Johanna and Fritz Kempe Memorial Scholarship helps fund studies of older, nontraditional students at the U.

"What she did was much more difficult and challenging when she did it," said Robert Newman, dean of the U.’s College of Humanities. "In many ways, she became a model."

Frederick Kempe, himself a U. alumnus and now CEO of the public- and foreign-policy think tank Atlantic Council in Washington, D.C., said his new book follows in the renegade spirit of his mother’s life. A copy editor at The Salt Lake Tribune from 1974 to 1976 before going to The Wall Street Journal, Kempe is delighted that his late mother will be honored four days before the release of his latest book.

Kempe said Berlin 1961 is sure to upset some of world history’s most hallowed assumptions about the United States’ Cold War with the Soviet Union, with Germany’s then-former capital city caught in the middle. The most startling assertion of his book is that the Cuban Missile Crisis could have been averted if not for President John F. Kennedy’s naive dealings with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.

The book took six years to write, with Kempe drawing upon Khrushchev’s memoirs, many heretofore untranslated, plus Kennedy’s assessment of his own foreign policy during his first year in office. Kempe concludes that Berlin — and perhaps all Eastern Europe — could have been spared decades of Soviet domination if not for the young U.S. president’s missteps.

Kempe charges that Kennedy failed to give Khrushchev credit for abandoning Stalinist platforms, reducing Soviet defense spending and acknowledging past Soviet troop withdrawals from Finland and Austria. Kennedy then misread the Soviet ruler’s interests in Germany, believing Khrushchev would become amenable to other foreign-policy issues if refugees stopped flowing out of East Germany. Instead, Kempe’s book documents, a young Kennedy, terrified of nuclear confrontation, "wrote the script" for Berlin’s sacrifice to the Soviets. The book asserts that Kennedy could have moved decisively to thwart construction of the wall because Khrushchev had not fully consolidated power.

The jacket of Kempe’s book boasts favorable words from Zbigniew Brzezinski, national security adviser to former President Jimmy Carter, who called it "history at its best."

"I really want to start a new debate about that period," Kempe said from his Washington, D.C., office. "Was Kennedy a hero for what he did in Cuba? Or should we condemn him for what happened in Berlin? I fall more on the other side of that fence."

Although Kempe’s father hailed from a small town in eastern Germany, it was always Berlin that earned the lion’s share of the family’s attention. If his mother were alive today, Kempe believes, she would have enjoyed reading his book — after, of course, finishing her dissertation.

"The last time I saw her was in the stacks of the [U.’s] Marriott Library," he said.

Also see a tribute to her in the College’s Kingfisher newsmagazine, "Straight to Her Goal – Johanna Kempe’s Pursuit of Life-long Learning."

Fred Kempe is president and CEO of the Atlantic Council. His latest book, Berlin 1961, will be available May 10.

Image: johanna%20front%20page.jpg