Atlantic Council board director Zalmay Khalilzad, a former ambassador to Afghanistan and the United Nations, worries in the Washington Post today about what he calls the Obama administration’s “country-specific” Mideast strategy. The newspaper’s headline reads, “The Mideast needs an innovator, not a spectator.”

In the current state of Mideast confusion, it’s understandable that U.S. officials would conclude that what’s good for Egypt or Tunisia can’t apply to Libya or Saudi Arabia. And no one believes a one-size-fits-all approach can work. The countries are too different in history, governance and importance to U.S. interests for that. What we’re also witnessing is further implementation of the Obama administration fixation, from the campaign to this moment, on not being George W. Bush. (As one former White House official described it, “They consider Bush Jr. Wilsonianism with a sword.”)

However, as Khalilzad rightly argues, the country-specific strategy fails to fully recognize two facts. First, U.S. action (and inaction) in one country drives events in others. Second, it puts the Obama administration in more of a reactive mode when it should help shape history. Witness the Saudi march into Bahrain, where Riyadh filled the U.S. policy vacuum with its own answer. And if the U.S. remains on the sidelines, all the declarations of the Arab League and French leader Nicolas Sarkozy won’t stop an increasingly inevitable Qadhafi victory.

French Foreign Minister Alain Juppe declared “the moment has passed” to impose a NATO no-fly-zone over Libya. The Financial Times reports that the UK and France “have lost hope of launching military action” to stop Qadhafi’s assault on the rebels – and some military analysts tell me that Benghazi’s fall to his loyalist forces could be a matter of days.

The costs will go far beyond Libyan borders. The Council on Foreign Relations’ Max Boot, who believes it’s not too late to reverse course in Libya, argues in today’s Wall Street Journal that failure will encourage other Middle Eastern despots to follow Qadhafi’s example:

“The Arab Spring could easily turn into a very dark winter that will arrest and reverse the momentum of recent pro-democracy demonstrations. That means consigning the entire region to a dysfunctional status quo ante in which the long-term winners will be al Qaeda and their ilk.”

So what to do?

First, there is always ample space between “Wilsonianism with a sword” and inaction. Washington makes a mistake in dividing itself up between realists and idealists, whereas the most effective policy in almost any situation requires doses of both tendencies.

Khalilzad suggests a proactive regional strategy that differentiates between friendly authoritarians and anti-American dictatorships. In Iraq, Egypt and Tunisia, he suggests steering democratic transitions under way to success. In friendly but non-democratic states, he suggests Obama should encourage political reforms and push ruling regimes toward creating constitutional monarchies that open up space to responsible actors. In that context, one can then differentiate toward someone like the Libyan dictator, a despot vilified by the region and whose survival may have greater risks for the United States than supporting action against him.

The best argument against a country-specific approach is that it misunderstands the historic moment. Argues Khalilzad:

“We are at a key juncture. As in Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the dysfunction of the Middle East today generates the most threatening challenges to the international community. The largely peaceful, youth-oriented, democratic revolutions across the region present an opportunity to catalyze a fundamental transformation.”

History provides moments like this one only once or twice in a century – and this one has regional and global implications. The Obama administration thus must frame a more strategic response, working in particular with European partners, that is at the same time humble and pro-active.

When I recently asked General Brent Scowcroft how he, as national security adviser to George H. W. Bush, decided when to be more and when to be less assertive during the heady days of German unification and Soviet collapse, he answered: “It’s always a question of judgment.” One always must make policy choices with imperfect knowledge and without knowing the outcome, he says. The best chance of success comes only from understanding the playing field, judging American interests, and then calculating both our limits and capabilities.

Perhaps that’s the crux of the problem. We’re seldom blessed with a geostrategic thinker like Brent Scowcroft when history calls.

Fred Kempe is president and CEO of the Atlantic Council. His latest book, Berlin 1961, will be available May 10. Compiled with Borjan Zic. Photo Credit: Reuters Pictures.

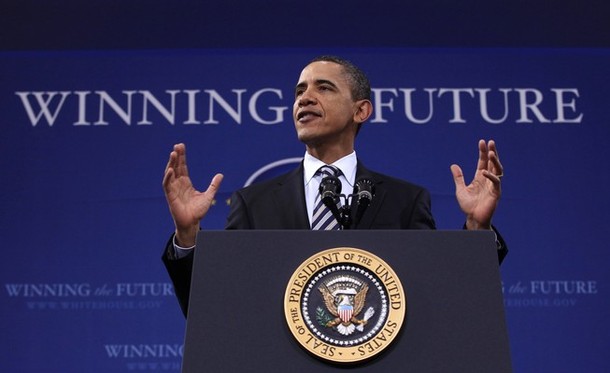

Image: obama-winning-future.jpg