Book promotion has its indignities and high points.

The indignities thus far have come from America’s polarized political debate trying to fit a serious history of 1961 into its ideological framework – as if everything in the world has to be crammed into this simplistic division of thought. Some conservative radio hosts are a little too ready to embrace my book, welcoming the explosion of the Kennedy-Camelot myth, while a few too many liberals want to condemn it because it forces a re-examination of one of the Democratic Party’s most celebrated presidents.

The reason that my book Berlin 1961 has been critical of Kennedy’s foreign policy performance during 1961 is because the documents and the evidence lead there. As a self-described radical centrist, I have no bone to pick with Kennedy – but rather want the U.S. to understand the forces behind the history that shaped the Cold War. I don’t argue he should have started a war to stop the Berlin Wall, which no one wanted, but rather want the reader to rethink the conventional wisdom of whether by acquiescing to the Berlin Wall he really helped avoid nuclear war and created a safer world – or whether he may have served to extend the Cold War.

A year made up of the Bay of Pigs, the Vienna Summit and the Berlin Wall’s construction can hardly be construed as a success – particularly when followed a year later by the Cuban Missile Crisis, executed by a Soviet leader who by his own words had concluded from 1961 that he could get away with it. Kennedy was self-aware enough himself to call his 1961 performance “a series of disasters,” when speaking to then-Detroit News bureau chief Elie Abel. He worried deeply that Khrushchev had concluded he was weak and would thus test him further – and he turned out to be right.

The high points in book promotion come from the many interviews and reviews that seriously digest the book’s seven years of research and 500 pages of text – and then help readers make sense of it all for their present context. They’ve included Charlie Rose, MSNBC’s Morning Joe, C-SPAN, the Wall Street Journal, the Huffington Post, Commentary and a host of other radio, TV and newspaper outlets from around the country. We have a country hungry for this sort of serious discussion.

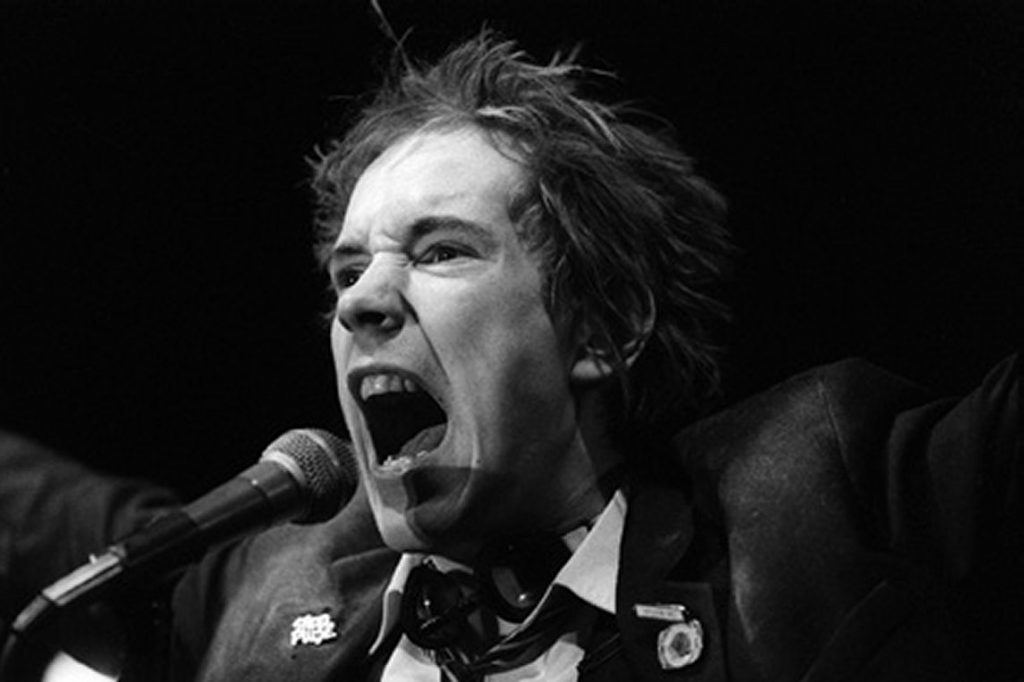

This week marked a particular high point as the reviewer for the Washington Independent Book Review, Y.S. Fing, challenged his readers to do two things to understand Berlin 1961: read my book and listen to Johnny Rotten and his band the Sex Pistols play their song, “Holidays in the Sun,” in which tourists visit the Wall and watch those on the other side.

It’s a catchy lead for a review that more seriously captures the richness of characters and forces that shaped the Berlin Crisis in 1961. He focuses on the vignettes in my book the capture some of the lesser characters that create Berlin’s texture:

“…the stories of those powerless to the tide of history, among them Günter Litfin, the first East German shot dead trying to break out. There is also Eberhard Bolle, a West German student who spent four years in prison after attempting to deliver a West German identification to an East German classmate. Through these stories and various others, we see both the necessity (to the East Germans and the Russians) and the horror and frustration (to the Western world) of the building of the Wall.”

The Washington Independent Book Review also has avoided the temptation to fit Berlin 1961 into any ideological prism but instead presented the facts of my conclusions. The author concludes that while Kennedy was concerned with avoiding nuclear war over Berlin, Khrushchev more was concerned with avoiding the collapse of East German, perhaps all of Eastern Europe and the Soviet regime itself. He rightly concludes that I think the Wall allowed Khrushchev to head off these possibilities.

Here he reproduces the striking exchange between Khrushchev and Ulbricht after the Berlin border is closed.

Khrushchev: “When the border is closed, the Americans and West Germans will be happy.”

Ulbricht: “Yes, and we will have achieved stability.”

But, of course, at the expense of the lives of East Berliners – and tens of millions of others in eastern and central Europe.

Fred Kempe is president and CEO of the Atlantic Council. His latest book, Berlin 1961, was published May 10.

Image: johnny-rotten.jpg