Morocco’s government must foster greater economic competition

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

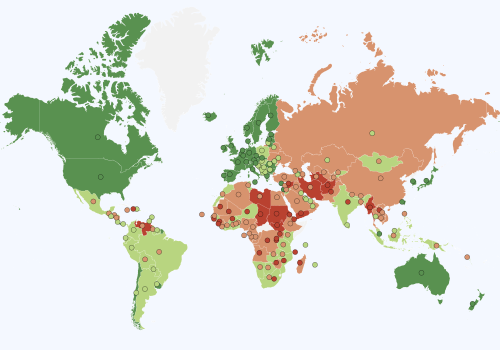

Morocco has substantially improved in all institutional dimensions during the last three decades, as measured by the progress in the Freedom Index. The Kingdom navigated the Arab Spring, which rocked certain countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. As a result, a diverging trend has emerged between the sustained improvement in Morocco and the deterioration in MENA’s regional average since 2013, resulting in a gap of more than eleven points in their respective Freedom Index scores. As this chapter will detail, there are many areas in which Morocco still needs to continue its reform effort toward fully free and open institutions, building on recent positive trends.

The economic subindex shows a very sharp discontinuity in the year 2004, where Morocco’s score jumps more than eight points, opening a very substantial gap with respect to the rest of the region. A closer look at the components included in the economic subindex evinces that it is primarily driven by an extensive improvement in women’s economic opportunities, produced by the implementation of a new Family Code, known as Moudawana, in 2004. This piece of legislation is seen as one of the most progressive of the region, expanding women’s rights and protections in relation to civil liberties like marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance; as well as labor and economic aspects such as workplace protection, equal pay, maternity leave, and access to credit.

Morocco has historically been fairly open to international trade and foreign investment. The European Union-Morocco Association Agreement that entered into force in the year 2000, creating a free trade area with the European Union, has certainly expanded exporting opportunities. Yet, the concentration of trade relations with Europe may have slowed down economic integration with neighboring countries in the Middle East and Africa. The signing of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement in 2018, and its ratification in 2022, will likely favor the expansion of Morocco’s trade and investment flows with the rest of Africa in the coming decades.

The different components of the economic subindex are not wholly capturing domestic aspects of free and fair competition. Like in most countries in the Middle East and North Africa, Morocco is subject to an important level of market concentration in many sectors, especially non-tradable sectors. That is despite progress made in the competition policy framework. Leveling the playing field will be paramount if Morocco wants to ignite productivity and job creation.

The political environment in Morocco is complex, as evidenced by the large differences in the scores of the four components of the political subindex. Following the Arab Spring, a new Constitution was adopted which aimed at fostering more democracy, reinforcing the independence of the judiciary, combating corruption, and better protecting women and minorities. As a result of the new Constitution, judicial independence and effectiveness scores increased by ten points. While the Constitution brought important strides, critics argue that the concentration of power has not changed. Political rights in Morocco are better protected than in most other countries in the region, but the overall level is still far from the most advanced countries of the world. Freedom of expression is fairly protected, but it is limited. As a result, the press cannot fully fulfill its role as a public watchdog, including on issues of corruption. Morocco performs poorly in the bureaucracy and corruption component of the legal subindex.

The positive trend in terms of reduction of informality reflects efforts by the authorities to formalize the economy. The enrollment of informal workers into the public health system is, however, proving difficult. The trend in informality is linked to progress toward poverty reduction in Morocco. Yet poverty remains pervasive, especially in rural areas. The informal sector serves as a shock absorber, Evolution of Prosperity and as such, adopting a more inclusive approach as opposed to coercion is desirable. Reduction in barriers to entry into the formal sector is the way to go to reduce informality.

Evolution of prosperity

The evolution of the Prosperity Index since 1995 illustrates the sustained improvement in standards of living in Morocco, which has reduced the gap with the average of the MENA region. It is important to note that the regional average includes several low-population, oil-rich countries, namely the Gulf monarchies, which partially explains the persistent gap.

An important factor that increased the cohesiveness of Moroccan society, and certainly improved the recognition and protection of minorities, is the acceptance of the Berber language as official in 2011. This historic step has produced positive spillovers in terms of cohesiveness but it remains to be seen whether this will translate into reduced regional inequality in the medium term.

Regional inequalities are significant in several components included in the Prosperity Index, The Path Forward such as income, education, and health. Increasing economic prosperity in the last decades has disproportionately benefited urban populations in cities, which have also been the destination of most investments and growth-enhancing public policies. As a result, there are still sizable pockets where poverty is severe.

The performance of the educational system reflects that duality. While access to primary education has become universal, the quality of education is uneven. Indeed, the quality of education is much lower in rural than urban areas, further exacerbating spatial inequalities. The situation of the healthcare system is not very different, and suffers from several issues already mentioned, like the large disparities along the urban-regional divide.

The path forward

Overall, Morocco has made notable progress toward economic transformation, but further efforts to balance its economic development are needed. Morocco’s experience with economic development is unbalanced. On the one hand, there are pockets of rapid development, and on the other, pervasive poverty remains, especially in rural areas. In 2021, Morocco has started to implement a “new development model” to improve human capital, boost productivity, and foster inclusion. Despite the progress, economic growth remains tepid and poverty is pervasive. What is more, Morocco is faced with a relatively high level of debt. The lack of fiscal space constrains government spending to reduce spatial disparities and support poorer households.

The danger for Morocco is that it could remain stuck in a so-called middle-income trap with low growth and high poverty, which could further ignite social tensions. To reignite growth and transform its economy, Morocco must level the playing field. To do so, issues of market structure and competition must become more central. That would help jumpstart productivity and create good jobs. Take the example of the telecom sector, where anti-competitive practices have long made the quality and cost of digital services expensive.

Barriers to the adoption of so-called general-purpose technology such as quality and affordable internet are an important factor keeping Morocco in the middle-income trap, and also could further the divide between urban and rural areas. The pervasive lack of contestability, and the slow pace of technology adoption, help explain why Morocco is stuck in low growth. Governments play a key role in the regulation of entry in key “upstream” sectors such as telecom. Meanwhile, the lack of availability of frontier technology may have forced firms into low-productivity activities and limited their trade and economic growth.

More generally, unfair competition that results from markets dominated by connected firms deters private investment, reducing the number of jobs and preventing countless talented youngsters Rabah Arezki from prospering. This lack of fair competition is the underlying reason that Morocco, like other Middle East and North African economies, is unresponsive. The lack of contestability leads to cronyism and what amounts to rent-seeking activity, including, but hardly limited to, exclusive licenses, which reward their holders and discourage both domestic and foreign competition.

Morocco has adopted a competition framework to champion open competition, but the limited independence of the competition authority reduces its ability to decisively shape the market structure of the economy. An integral part of the competition and contestability agenda is transparency and data availability. Morocco, like other countries in the Middle East and North Africa, trails behind other similar middle-income countries on government transparency and the disclosure of data in critical areas on the degree of competition in sectors. Greater transparency would help build a consensus over the need for more competition to stimulate growth and job creation.

Rabah Arezki is a former vice president at the African Development Bank, a former chief economist of the World Bank’s Middle East and North Africa region and a former chief of commodities at the International Monetary Fund’s Research Department. Arezki is now a director of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Studies and Research on International Development, and at Harvard Kennedy School.

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous Edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the data

About the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: A peacock and other birds are seen in Jemaa el-Fnaa square, in Marrakesh, Morocco, October 21, 2024. REUTERS/Stelios Misinas

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media