Developing and emerging economies should double down on trade liberalization

Bottom lines up front

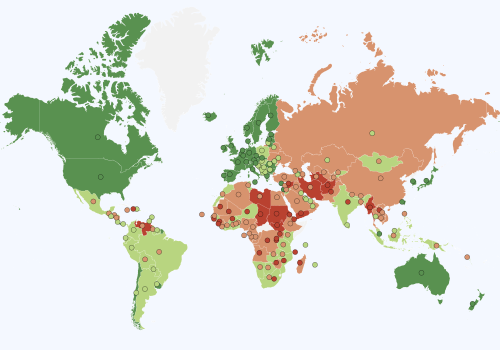

- An unpredictable and protectionist US trade policy will limit emerging and developing economies’ market access, weaken their ability to use exports to boost development, and weaken their growth potential.

- Emerging economies should resist adopting protectionist policies, and instead recommit to international trade and financial integration.

- Emerging economies should take advantage of global efforts to diversify supply chains by strengthening macro fundamentals and creating an attractive domestic environment for foreign direct investment.

The sharp shift toward a difficult-to-predict and protectionist US trade policy has increased short- and long-term global economic uncertainty. Many emerging and developing economies (EDEs) potentially face significantly higher US trade barriers if the reciprocal tariffs announced (and immediately suspended) in early April come into effect in July. The Trump administration has introduced, and is in the process of introducing, additional sectoral tariffs. To what extent individual economies will be affected by US protectionist policies, including secondary effects, will be a function of their respective export structure and financial vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, it is possible to make some broader observations.

US trade restrictions will hurt developing economies economically and financially

In political economy terms, the multilateral international trade regime helps limit the vulnerability of smaller, relatively more trade-dependent economies to economic coercion by larger, less trade-dependent countries. The weakening of the international trade regime means that smaller and more open economies become more susceptible to geoeconomic coercion. In narrower economic and financial terms, broad-based US protectionism will also have negative consequences for EDEs in a variety of ways.

First, higher US tariffs will hurt EDE exports to the world’s largest market for final consumption: the United States. The greater their dependence on the US market, the more directly EDEs will suffer by way of reduced exports, lower foreign-currency revenues, and, hence, lower economic growth (all other things being equal). Higher tariffs will lead to any combination of lower export volumes, lower export prices, and lower profit margin. Exporting companies’ lower profit margins will reduce corporate savings and limit their ability to invest. Related lower foreign-currency revenue will represent a particular challenge to highly indebted, financially distressed countries where macro-stability is already fragile.

Second, higher US tariffs will directly and indirectly impact US and global economic growth (all other things being equal). Lower global economic growth will weigh on commodity prices. Many economies, especially developing economies, are highly dependent on commodity exports. Continued US-China trade tensions also threaten to reduce Chinese growth and, by extension, demand for commodities and demand for developing economies’ exports. China is currently the largest trading partner for more than 120 countries.

Third, to the extent that US tariffs lead to higher US inflation, they will likely keep US interest rates higher for longer, while global uncertainty will likely translate into increased global investor risk aversion. This diminishes the ability of many—especially financially weaker emerging economies and most developing economies—to raise financing at a time of increasing borrowing costs.

Fourth, if broad-based US protectionism leads to a stronger dollar, financial distress in fragile developing economies will increase further due to the higher financing costs in local-currency terms at a time when export-related revenues are under pressure from higher tariffs. However, contrary to the historical pattern, the dollar has weakened recently in the face of increased economic and financial uncertainty (at least in trade-weighted terms).

Fifth, US tariffs will lead to trade diversion, meaning that countries that cannot export to the United States will seek to redirect exports to other markets. To the extent that emerging economies—and, less so, developing economies—compete with, for example, Chinese manufacturing exporters, domestic producers and the economy will be faced with increased import competition as well as more intense competition in third markets. This will also increase the risk of additional trade restrictions in countries affected by trade diversion.

Sixth, and more structurally, reduced access to overseas markets like the United States will limit developing economies’ longer-term growth potential. Some countries have been highly successful in terms of taking advantage of international market insertion and economies of scale, and in sustaining a virtuous investment-export cycle by exploiting their comparative advantage. Relatively unfettered access to the largest market for final consumption, the United States, helped them to move up the technological, value-added ladder. With the United States imposing greater market access barriers, this type of economic development strategy will become more difficult to pursue successfully.

Maintaining import tariffs is of limited use to emerging and developing economies

Counterintuitively, EDEs faced with a panoply of economic and financial challenges should seek to offset reduced international market access as best as they can, by advancing reciprocal trade liberalization or, if this proves politically unfeasible, by pursuing a gradual, unilateral trade liberalization strategy flanked by broader economic policy and structural reform.

As Dartmouth professor Douglas Irwin has pointed out, protectionism has three economic rationales: restriction, reciprocity, and revenue. None of these rationales applies much in most EDEs from an economic cost-benefit point of view. First, import restrictions have been part of some countries’ successful industrialization and economic development strategies—though economists differ on how central they were to successful economic development. While several countries have successfully developed against the backdrop of a strategic industrial policy flanked by import restrictions, other countries characterized by the same policy mix have proven less successful. More often, countries have failed to implement long-term, infant-industry-oriented industrial policy and trade strategy in the context of state capture and rent seeking (e.g., in Latin America). Regardless, in cases where the implementation of such a developmental strategy has little prospect of success due to rent seeking and state capture, countries are better off gradually removing trade restrictions to generate efficiency gains. Broadly, EDEs should lower tariffs on imports to increase domestic competition, generate efficiency gains, and increase productivity.

Second, threatening reciprocal retaliatory measures is meant to deter other countries from unilaterally imposing trade restrictions. Reciprocity also provides a bargaining chip in terms of granting others greater market access to gain tariff concessions. However, for many emerging economies, especially developing economies, the reciprocity rationale is largely irrelevant in terms of gaining access to the world’s larger economies: the United States, China, and the European Union (EU). These smaller economies’ trade concessions are generally too limited to induce larger countries to grant greater market access. They matter little to the larger economies. Countries can maintain tariffs while intending to trade them away in bilateral negotiations with similarly sized countries. But the economic prize is access to large, advanced economies—not less developed, smaller economies.

Third, tariffs often represent an important source of government revenue, particularly in developing economies with limited tax bases. This especially constrains developing economies’ ability to lower tariffs. Many countries cannot eliminate import tariffs overnight without undermining public finances, even if tariff reductions lead to aggregate welfare gains. In these cases, a gradual, phased-in tariff liberalization policy accompanied by domestic revenue generation and tax reform is advisable.

The benefits of free trade are theoretically and empirically well-established.1 Under standard assumptions, free trade is almost always economically preferable to trade restrictions from a welfare perspective. In brief, free trade allows for specialization and enhanced efficiency, leading to aggregate welfare gains. Trade integration can also help facilitate investment and technology transfers. Free trade also lowers the prices of imports, which benefits consumers and importers of intermediate goods.

Emerging economies need to strengthen their macroeconomic and financial resilience

Increased economic and financial uncertainty, potentially higher interest rates, lower commodity prices, and reduced market access should spur EDEs to double down on growth- and efficiency-enhancing trade liberalization. In view of the risks they face, EDEs should strengthen their financial position, enhance the resilience of their domestic macro-policy regimes, and pursue tariff liberalization—ideally in the context of reciprocal trade agreements or, if necessary, through unilateral liberalization.

Strengthen macroeconomic governance and policies to enhance domestic economies’ ability to absorb trade-related shocks: This should be flanked by efforts to create greater macroeconomic and fiscal space to pursue counter-cyclical policies, or at least to let automatic stabilizers take effect in cases of trade and other external shocks. First, they should establish independent central banks committed to maintaining low inflation. Second, they should introduce a fiscal policy regime that limits the government’s ability to run large deficits for an extended time and keep debt at manageable levels. Third, they should move toward a flexible exchange-rate regime to allow them to absorb more easily adverse balance of payments and other trade-related shocks without suffering broader economic and financial destabilization.

Strengthen external financial positions to make balance-of-payments positions less vulnerable: Developing economies—and even emerging economies, despite their more limited foreign-currency mismatches—should strengthen their external financial positions to adopt a more flexible exchange rate capable of absorbing external shocks. This should be done via a reduction of foreign-currency liabilities. More trade openness will make it easier to earn foreign currency but will also make the economy more susceptible to trade-related and other external shocks. Therefore, these economies should reduce their financial vulnerability and strengthen the resilience of their macroeconomic policy regimes.

Emerging and developing economies should double down on international trade and financial integration

The economic and political cases for maintaining high tariffs are weak. To offset the efficiency losses due to higher global tariffs, and to increase economic gains in terms of domestic competition and trade specialization, EDEs should move toward greater trade liberalization in the context of strengthened fundamentals and a more resilient, rule-oriented, and credible domestic policy regime. EDEs should pursue quasi-multilateral, regional, or bilateral trade liberalization. If this proves politically difficult, they should take gradual, phased-in steps.

Pursue reciprocal trade liberalization or, if necessary, gradual unilateral liberalization of import restrictions: In the context of global overcapacity, unilateral trade liberalization might create a short-term drag in terms of demand and economic growth. Opening one’s markets could be negative for short-term economic growth. But in the longer term, this will help offset some of the efficiency losses due to higher US tariffs. While multilateral trade liberalization is economically preferable, unilateral tariff liberalization also enhances aggregate welfare. Given how many developing (and, to a lesser extent, emerging) economies depend on tariff revenue, they should proceed gradually. Tariff liberalization should be accompanied by fiscal reform to replace the prospective loss of tariff revenue.

Diversify export markets to reduce vulnerability to any country imposing wide-ranging trade restrictions: EDEs should prioritize trade liberalization with the larger economies, such as the EU and China. These efforts should be flanked by the liberalization of trade with other big, advanced, and emerging economies, such as Japan, South Korea, and Brazil, for example.

Align regulatory policies with major trading partners to reduce non-trade barriers and facilitate trade: As in the case of export diversification, EDEs should consider aligning their regulatory policies with those of their major trading partners, especially the EU and China, to reduce such barriers.

Create an attractive investment environment for foreign companies to take advantage of international companies’ efforts to diversify their supply chains: Faced with protectionism and trade disruption, global companies are reengineering their supply chains. Countries should try not only to lower tariff barriers but to attract foreign investment, including through domestic structural reform, labor and product market liberalization, infrastructure investment, and an investment-friendly tax regime. They should also facilitate greater integration into global value chains. This should help foster technology transfer and innovation, while providing additional, relatively low-risk balance-of-payments financing in the guise of more stable foreign direct investment, as compared to short-term and portfolio investment.

Support diplomatic efforts to preserve the multilateral trade regime: EDEs should support salvaging the international free-trade regime—or what’s left of it. While developing economies might make little difference to the outcome, they should nonetheless lend unambiguous diplomatic support to any such efforts. If the United States largely exits the international trade regime, the remaining countries might be able to preserve it, which will disproportionately benefit EDEs in terms of market access and the ability to exploit economies of scale through an export-oriented economic growth strategy.

About the author

Related content

explore the data

Explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: A worker holds a rope in front of cranes during sunset at a port in Tokyo, Japan, December 9, 2015. REUTERS/Toru Hanai