Escaping China’s shadow

China’s major financial commitments to Africa, coupled with its double digit returns, have discouraged American companies from breaking into African markets. Amid growing concerns regarding China’s expanding economic influence on the continent, a reassessment of America’s business edge and overall competitiveness is past due.

Rather than engaging in a fist-fight for influence with Chinese competitors, “Escaping China’s Shadow: Finding America’s Competitive Edge in Africa” argues that US companies should instead focus on their strengths and be more artful in leveraging the United States’ competitive advantages in unoccupied or less occupied spaces. Hruby outlines these ripe investment opportunities for US companies and maps a path to American business success on the continent.

This issue brief is part of a partnership between the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center and the OCP Policy Center and is made possible by generous support through the OCP Foundation.

Finding America’s competitive edge in Africa

Over the past decade, Africa has been cast as a new battleground for influence between the United States and China. China’s economy has experienced meteoric growth since the 1980s, and China has looked to Africa’s natural resources to help fuel this rise. In the process, China has rapidly increased its trade and commercial relationships with African nations. Chinese business people and migrants have swept across the continent as part of China’s broader “going out” strategy and its new Belt and Road Initiative.

The Donald Trump administration is hearing concerns from American companies that they face a competitive disadvantage against China in African markets. But, while it is true that China’s presence on the continent has dramatically grown since 2001—the trade relationship went from $10 billion to $220 billion in fourteen years1Statistics from 2000 to 2014. Lisi Bo Zhou Huang Yin, “With Trade Volume Up to Billions of Dollars, China-Africa Trade Takes a Step Further,” China Securities Journal, December 5, 2016, http://www.cs.com.cn/xwzx/hg/201612/t20161205_5110828.html.—it is not true that the presence of Chinese companies precludes American business success. American companies simply need to be more artful in leveraging the United States’ competitive advantages. As ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu observed, “if you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles . . . in war, the way is to avoid what is strong, and strike at what is weak.”2Sun Tzu, Art of War, https://suntzusaid.com/book/3/18, online version.

Operating in an era of constrained budgetary resources and “America First” thinking, policy makers crafting commercial aspects of US-Africa policy should focus on sectors in which US companies have a distinct competitive edge and not force competition in areas that have long been ceded to other global players. This would not be hard to do: Chinese commercial interests in Africa have, to date, been highly concentrated in only a handful of sectors—infrastructure, manufacturing, and extractive industries.3Wang Teng, “Standard Chartered: China-Africa Trade Grows Steadily,” Chief Executive China, July 10, 2015, http://www.ceconline.com/import_export_trading/ma/8800074494/01/?pa_art_6. Policy makers should also prioritize programs, partnerships, and projects that effectively support US small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)4SMEs are defined as independent businesses with fewer than five hundred employees. See “Frequently Asked Questions,” US Small Business Administration, September 2012, https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/FAQ_Sept_2012.pdf. to grow through success in African markets.

Improvements in macroeconomic policy and business environments in countries throughout Africa are creating a rapidly expanding opportunity set, and there is plenty of room for American companies heretofore focused on domestic US growth to look to the continent for fresh opportunities.

US investment in Africa – continuing a historical pattern

US investment in emerging economies—in China, India, Brazil, Eastern Europe, Mexico, etc.—has tended to follow a pattern. First, large multinational corporations (MNCs) export to a country to test demand, learn the market, and build commercial relationships. Then, once sales achieve a critical mass, MNCs invest in local production and assembly plants to shorten supply chains, reduce costs, and gain a stronger foothold in the market.

US investment in Africa has, so far, followed this pattern. The first wave of US investment in Africa was dominated by the large Fortune 500 companies that have long been global. General Electric, for example, has been in Africa for more than a century.5“GE in Sub-Saharan Africa,” GE, http://www.ge.com/africa/company/ge-sub-saharan-africa. Coca Cola has put foreign direct investment (FDI) into 145 bottling plants, about three thousand distribution centers, and more than seventy thousand employees across Africa.6Earl Nurse, “The Secret Behind Coca-Cola’s Success in Africa,” CNN, January 21, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/01/21/africa/coca-cola-africa-mpa-feat/. P&G invested in a diaper factory in Nigeria to cater to a burgeoning population, and Cargill constructed a cocoa processing facility in Ghana, one of the world’s largest cocoa producers.

The success of the first wave of American investors in emerging markets then encourages other MNCs that were late to the game and SMEs to follow suit. Once the market is demystified in mainstream business media and market signals are positive, smaller companies will generally follow the large ones into the fray.

Given their relative global inexperience . . . many American SMEs will face a steep learning curve in African markets.

US commercial involvement in Africa is now at that critical inflection point between MNCs paving a path and SMEs following: the latter are beginning to find their way to the continent. As of the 2010 census, there were 27.9 million American SMEs, far more than the 18,500 large firms in the United States. SMEs that are export-oriented tend to grow more quickly, create more jobs, and pay better wages than those that do not export.7“Frequently Asked Questions,” US Small Business Administration, https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/FAQ_Sept_2012.pdf. And African countries’ demographic trends and market fundamentals present a good opportunity for American SMEs to grow through mutually beneficial trade.8Africa’s middle class is growing, along with its spending power—McKinsey’s Lions on the Move II report estimates that by 2025, collective household spending in the continent’s fifty-four countries will reach $2.1 trillion, an annual average growth rate of 4 percent. By comparison, India, whose population is currently roughly similar to Africa’s, has private consumption expenditure of $1.3 trillion, and Brazil’s household final consumption expenditure in 2014 was $1.5 trillion (in 2014 US$). Business spending in Africa, already at $2.6 trillion in 2015, is expected to reach $3.5 trillion by 2025. On average, sub-Saharan Africa spent 30 percent of its GDP on imports of goods and services in 2015, and in some countries, the numbers were much higher. See “India Consumer Close-Up,” Goldman Sachs, Equity Research, June 1, 2016, http://www.goldmansachs.com/our-thinking/pages/macroeconomic-insights-folder/rise-of-the-india-consumer/report.pdf; “Brazil – Household Final Consumption Expenditure,” IndexMundi, http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/brazil/household-final-consumption-expenditure; Jacques Bughin, Mutsa Chironga, Georges Desvaux, Tenbite Ermias, Paul Jacobson, Omid Kassiri, Acha Leke, Susan Lund, Arend Van Wamelen, and Yassir Zouaoui, “Lions on the Move II: Realizing the Potential of Africa’s Economies” McKinsey Global Institute, September 2016, http://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/middle-east-and-africa/lions-on-the-move-realizing-the-potential-of-africas-economies.

Given their relative global inexperience, however, many American SMEs will face a steep learning curve in African markets. Policy makers can assist them by identifying areas in which US companies are competitive and then developing supportive policies to expand the number of SMEs enjoying foreign market success.

Instead of blindly complaining about Chinese infrastructure projects in African markets, stakeholders in the US-Africa business community should gravitate around a high-level Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis that defines the areas of advantages and disadvantages of American companies as they compete with their Chinese, Turkish, Russian, and European counterparts. Taking the time to have the self-reflective dialogue—at least in broad strokes—would allow US players to have a greater understanding of their own and their competitors’ strengths.

Measuring US competitiveness and determining sectors of focus

Measuring the competitiveness of US companies operating in foreign markets relative to their global counterparts is extremely difficult. Within statistical agencies of the US government and academia, there is no consensus on how to measure the competitive advantages of US businesses operating abroad and the large number of different measurements makes it hard to use any one in isolation. However, by layering four measures and indicators that already exist—foreign direct investment flows into the United States, sectoral contribution to US gross domestic product (GDP), the largest American global companies within a particular sector, and industries historically promoted by the US Department of Commerce—it is possible to begin to define the sectors in which American firms are most competitive.9First, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows provide insights into what foreign investors see as a country’s strengths—where sophisticated and experienced investors from abroad decide to put their money is an indication of how competitive they find those sectors to be. Second, examining the sectors with the highest contribution to the economy can give us an approximate idea of the sectors in which economic players in the United States are specializing and, thus, where the country has, very generally, strengths that can be realized on a global stage. Third, looking at the largest American global companies helps to pinpoint the sectors in which the United States has established strong enterprises that compete on a global level. Finally, US commercial agencies like the International Trade Administration and the Export-Import Bank work to promote US exports and advance the competitive position of American businesses in the global market; looking at the sectors on which these agencies choose to focus is yet another good way to help create a layered metric of where the US is competitive.

American sectors positioned for success in African Markets

Layering these four measures for American competitiveness brings five sectors to the forefront:

Professional and business services

American companies were the pioneers of the service economy—Arthur D. Little, a firm founded in Boston, was the world’s first management consulting firm10“The Birth of Management Consulting,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, https://betterworld.mit.edu/birth-management-consulting/.—and the Unites States has been a dominant player in the sector ever since. Professional services have, at times during the last several years, been one of the fastest growing sectors for incoming FDI and continue to be one of the largest contributors to American GDP.11“Foreign Direct Investment in the United States” Organization for International Investment, 2016, http://ofii.org/sites/default/files/Foreign%20Direct%20Investment%20in%20the%20United%20States%202016%20Report.pdf. Growth in FDI for a particular sector varies from year to year, for any number of reasons. In 2012-2013, information was one of the fastest-growing sectors, along with finance and insurance. Over that time period, professional, scientific, and technical services actually saw less FDI inflows. From 2013 to 2014, though, information saw fewer inflows, while professional, scientific, and technical services saw more. See also “News Release,” Bureau of Economic Analysis, January 19, 2017, https://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/industry/gdpindustry/2017/pdf/gdpind316.pdf. Strengths include legal, accounting, strategy consulting, higher education, and engineering and design services.

As African companies grow in terms of revenue and reach, the business environment in which they operate becomes more sophisticated, particularly if they begin to attract international private equity investment or if they expand across borders. Companies providing professional and business services support that growth.

Accounting firms are a perfect example. As African companies get larger, they may want to turn to capital markets for funding. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange, with a market capitalization over $1 trillion, is the most well-known option in Africa, but some African firms choose to list on exchanges in New York, London, or elsewhere. Listing on any reputable exchange requires competent third party auditors and accounting firms such as PwC, EY, or Deloitte. Outside of public offerings, African firms that take on private equity will also consume accounting and consulting services.

American expertise in the consulting field can also help growing African firms adopt global best practices to become more efficient and profitable. McKinsey’s work in African markets is a good case study: East African Breweries hired the firm in 2014 to advise on distribution and increase efficiency in logistics operations. Britam, a regional insurance and financial services firm, also engaged McKinsey to help manage the integration of an acquisition.12Herbling David, “McKinsey Opens Nairobi Office with Eye on East Africa,” Business Daily, August 6, 2014, http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/Corporate-News/McKinsey-opens-Nairobi-office-with-eye-on-East-Africa/-/539550/2410806/-/q9t1qcz/-/index.html.

Finance

The United States is a financial powerhouse: it accounts for five of the world’s top ten global financial centers.13Alex Tanzi, “London Remains Ahead of New York as Top Global Financial Center,” Bloomberg, September 26, 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-09-26/london-remains-ahead-of-new-york-as-top-global-financial-center. Going beyond traditional banking or insurance, American finance has also developed very high levels of expertise in venture capital and it has led the world in private equity investing. In 2012, for example, 68.6 percent of all global venture capital was American, and, in 2016, funds headquartered in North America accounted for 69 percent of the capital raised by the top three hundred private equity firms throughout the world.14Richard Florida, “The Global Cities Where Tech Venture Capital Is Concentrated,” The Atlantic, January 26, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/01/global-startup-cities-venture-capital/429255/; Marine Cole, Isobel Markham, and Toby Mitchenall, “PEI 300,” Private Equity International, 2016, https://www.privateequityinternational.com/uploadedFiles/Private_Equity_International/PEI/Non-Pagebuilder/Aliased/News_And_Analysis/2016/May/Magazine/PEI300 percent202016.pdf. Alongside the development of new internet- and mobile-based financial technologies over the last two decades, the United States is ranked the number one country on the Global Cybersecurity Index for having cutting edge firms working in the sector.15“Global Cybersecurity Index & Cyberwellness Profiles,” International Telecommunications Union, April 2015, https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/str/D-STR-SECU-2015-PDF-E.pdf.

Lack of capital is a pervasive challenge in African markets. For individuals, basic financial inclusion remains elusive. The World Bank assessed that only 34 percent of sub-Saharan Africans over the age of fifteen had a bank account in 2014. Only 16 percent had formal savings, and 6 percent had access to formal borrowing methods.16“Financial Inclusion Data,” World Bank, http://datatopics.worldbank.org/financialinclusion/region/sub-saharan-africa. More recent sources suggest the numbers may have grown, but only slightly: Wim van der Beek, founder and managing partner of Goodwell Investments in South Africa, noted in 2016 that 80 percent of the continent’s adult population does not have access to formal financial services.17Wim van der Beek, “Fintech Isn’t Disrupting Africa’s Financial Industry—It’s Building It,” Quartz Africa, August 3, 2016, https://qz.com/749008/african-fintech-isnt-disrupting-the-financial-industry-its-building-it/. Banking the “unbanked” and unlocking financial flows are critical for economic development and growth. Informal markets are expensive and inefficient, limiting Africans to growth that can be funded only by day-to-day cash flows. Finding innovative ways to formalize more financial interactions is not only an area of exciting entrepreneurship in countries such as Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa, but also a ripe area for partnerships with American firms and investors.

Given the innovation around mobile money in African markets, cybersecurity is a fast-growing need. Mobile money has boomed in East Africa, and it is quickly spreading throughout the rest of the continent with Nigeria coming online in a big way. Kenya’s M-Pesa, Africa’s biggest player in the space, processed six billion transactions in 2016, worth tens of billions of dollars.18“Kenya Marks 10 Years of M-Pesa Transforming Lives,” Safaricom, March 7, 2017, https://www.safaricom.co.ke/about/media-center/publications/press-release/release/337. The sheer volume and value of mobile money has created platforms for savings, insurance, and consumer credit and the increasing economic importance of these platforms means that US cybersecurity firms have an opportunity to provide essential services to keep users’ money and data safe.

Media, entertainment, and information

The US entertainment industry dominates the global market. Nigeria’s and India’s film industries were named after Hollywood (“Nollywood” and “Bollywood,” respectively), and American music has made its way to even the most remote African villages. US presence in the media and information industries is equally strong. The Bloomberg Terminal and Thomson Reuters’ Eikon, for example, have together captured 91 percent of the worldwide financial information services market.19Trevir Nath, “Financial News Comparison: Bloomberg vs. Reuters (BAC, GOOG),” Investopedia, May 28, 2015, http://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/052815/financial-news-comparison-bloomberg-vs-reuters.asp. Google is so well known that its name has become a verb and it has few real global competitors in terms of search engine market share.20“What Are the Top Ten Most Popular Search Engines?” Search Engine Watch, August 8, 2016, https://searchenginewatch.com/2016/08/08/what-are-the-top-10-most-popular-search-engines/. Google’s search engine global market share is 72.48 percent, and Bing’s is 10.39 percent. Baidu, a Google-like company in China, has 7.14 percent of global market share. In terms of social media companies—Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat—the United States is equally dominant.

Recognizing the opportunity embedded in Africa’s young and growing population, Facebook and Google have set up operations in the region and are tailoring products to a mobile-first generation. Bloomberg has also undertaken initiatives designed to train African business journalists and bring business reporting and data from the continent to the world.21See Media Initiative Africa, Bloomberg, https://www.bmia.org/.

The creative industry is also burgeoning on the continent, as exhibited by the popularity of online series such as An African City and MTV Shuga, the emergence of musicians with global appeal, and the success of movies such as Beasts of No Nation, which appeared on Netflix. The entrepreneurs behind creative efforts, however, could benefit from the unique blend of American media and finance expertise. Raising capital locally for creative projects is incredibly difficult, as African banks lack experience with creative industries’ business models. The US film and music industries have long-standing partnerships with banks and funds such as JPMorgan and OneWest, which was formerly chaired by the current secretary of the Treasury, Steve Mnuchin.22Anousha Sakou, “Star-Struck Bankers Return to Hollywood to Finance Movies,” Bloomberg, June 19, 2014, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-06-19/star-struck-bankers-return-to-hollywood-to-finance-movies. Given their decades of experience, US funds could play a critical role in taking African creative industries to the next level in terms of profitability and sustainability.

Agribusiness

American agribusiness is industrial in nature, giving it significant research and development capacity, large economies of scale, and global reach. In the twentieth century, the United States developed strengths in agricultural machinery, seed production, and food processing, which found success in international markets. In addition, American agricultural technology has blended US expertise in venture capital, engineering, and agriculture to create new and innovative companies that farm using fewer resources to produce higher yields of high-nutrition fruit and vegetables. For example, the company Plenty has found a way to produce 150 times as much lettuce per square foot in warehouses than a farmer can produce outdoors, using 1 percent of the water.23For an example, see Jacob Bunge and Eliot Brown, “Indoor Farming Takes Root at California Startup,” Wall Street Journal, February 13, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/indoor-farming-takes-root-at-california-startup-1486981806.

Over 70 percent of all Africans depend on agriculture for their livelihoods.24Mamadou Biteye, “70 Percent of Africans Make a Living Through Agriculture, and Technology Could Transform Their World,” World Economic Forum, May 6, 2016, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/05/70-of-africans-make-a-living-through-agriculture-and-technology-could-transform-their-world/. Yet, African agriculture is among the most unproductive in the world—most Africans working in farming are smallholders, producing much smaller yields than their counterparts in other emerging markets. Given that the region is projected to need more than double the amount of food, feed, and biofuel in 2050 than it did in 2012,25Independent Task Force on Global Food Security, “Stability in the 21st Century: Global Food Security for Peace and Prosperity,” March 2017, https://digital.thechicagocouncil.org/Global/FileLib/Global_Food_and_Agriculture/Stability_in_the_21st_Century_March17.pdf. US agribusiness firms specializing in seeds, irrigation, machinery, and crop science have enormous potential to bring their expertise to bear on the continent for mutually beneficial outcomes.

Renewable energy

Although the United States lags behind other countries in some parts of the renewable energy sector (i.e., solar panel production), it has several competitive strengths such as engineering and high-quality product design. In 2015, the United States led the world in the production of biodiesel and fuel ethanol, and in bio-power generation.26“Renewables 2016: Global Status Report,” Renewable Energy Policy Network, 2016, http://www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/GSR_2016_Full_Report.pdf. It is also a leader in converting waste to energy (particularly for municipal solid waste) and in battery storage.27“Waste to Energy,” World Energy Council, 2013, https://www.worldenergy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/WER_2013_7b_Waste_to_Energy.pdf; Columbia University, “How Better Battery Storage Will Expedite Renewable Energy,” September 21, 2015, http://www.ecowatch.com/how-better-battery-storage-will-expedite-renewable-energy-1882097909.html.

Renewable energy has a central role to play in advancing African development. According to the 2016 World Energy Outlook, six hundred million Africans currently live without electricity.28“World Energy Outlook,” International Energy Agency, 2016, http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/resources/energydevelopment/energyaccessdatabase/. In 2013, the African Development Bank (AfDB) put Africa’s total installed power capacity at 147 gigawatts (GW). To address the energy infrastructure deficit, the AfDB found that the continent would need to add up to 250 GW by 2030, which would require an investment of $40 billion yearly.29“The High Cost of Electricity Generation in Africa,” African Development Bank Group, February 18, 2013, https://www.afdb.org/en/blogs/afdb-championing-inclusive-growth-across-africa/post/the-high-cost-of-electricity-generation-in-africa-11496/. There simply is not a way forward that does not heavily involve renewable and off-grid solutions, and the viability of those options often depends on innovations in battery storage. Matching unparalleled American design and engineering with the African market can provide new solutions that could free millions from energy poverty.

Sectors in which the United States is not competitive

Equally important to identifying areas of US competitiveness is understanding the sectors in which US companies fall short compared with companies from other regions. The United States is the mall, not the factory, of the world. From apparel to switchboards, light manufactured products are rarely stamped “Made in the USA.” Asian countries, with their fast growth over the last several decades and lower cost of labor, have developed highly competitive manufacturing clusters.

Since the 1980s, China has moved from producing basic clothing items to manufacturing iPhones. Asia also is home to seven of the top ten solar panel manufacturers, all of which received standard quality rankings.30Josh Bateman, “The New Global Leader in Renewable Energy,” Renewable Energy World, January 13, 2014, http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/articles/2014/01/the-new-global-leader-in-renewable-energy.html; “The Top Ten Solar Manufacturers,” Energy Sage, http://news.energysage.com/best-solar-panel-manufacturers-usa/. Energy Sage’s quality rankings are economy, standard, and premium. The only premium manufacturer on their top ten list was an American firm. There were no firms on the list that received an economy ranking. Although the United States has renewable energy niches in which it remains highly competitive, in 2015 China led the world in investment outlays directed to renewable energy, making up 36 percent of the global total, more than double the United States’ number.31“Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment,” Frankfurt School, UNEP Centre, 2016, http://fs-unep-centre.org/sites/default/files/publications/globaltrendsinrenewableenergyinvestment2016lowres_0.pdf.

A final example is building transportation infrastructure: given Chinese financing mechanisms, US companies are simply not competitive on the type of large-scale road, rail, and port projects in emerging markets that define China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Of the 250 global contractors ranked annually by Engineering News magazine, an industry publication, Chinese firms took the top four slots.32“The 2016 Top 250 Global Contractors,” Engineering News Record, http://www.enr.com/toplists/2016-Top-250-Global-Contractors1. While accurate and verifiable statistics on Chinese projects are hard to come by, Xinhua News Agency announced in 2015 that China had “completed over 1,000 projects in Africa, including 2,233 kilometers of rail construction and 3,350 kilometers of highway paving.”33William Wilson, “China’s Huge ‘One Belt, One Road’ Initiative Is Sweeping Central Asia,” The National Interest, July 27, 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/chinas-huge-one-belt-one-road-initiative-sweeping-central-17150.

The political context of limited resources for foreign engagement calls for an even more disciplined approach to prioritization in US-Africa commercial policy.

Chinese firms have negotiated major contracts to either rehabilitate or build rail infrastructure in Kenya, Ethiopia, Zambia, and a dozen other countries and have recently signed agreements in Uganda, Tanzania, and Nigeria. One of the most recent high-profile, Chinese-led projects is the 466-mile-long Djibouti-Ethiopia rail line. Almost all of the $4 billion in financing for that project came from Chinese sources.34Andrew Jacobs, “Joyous Africans Take to the Rails, with China’s Help,” New York Times, February 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/07/world/africa/africa-china-train.html. Given that American firms have not built notable rail projects in the United States for a century and funding gaps around the northeast corridor of Amtrak run in excess of $25 billion,352017 Infrastructure Report Card, Rail, American Society of Civil Engineers, https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Rail-Final.pdf. it is best that US policy makers focus on other sectors and accept the dominant role the Chinese play in infrastructure construction in African markets.

Recommendations

By incorporating a dialogue about competitiveness into US-Africa foreign and commercial policy, policy makers can better assess the effectiveness of existing programs and create new initiatives to efficiently support business ties between the United States and African countries. The political context of limited resources for foreign engagement calls for an even more disciplined approach to prioritization in US-Africa commercial policy—one that reduces the general noise about US-China rivalry in African markets and focuses on the areas in which American companies are more likely to succeed in advancing both US and African economic development objectives.

Recommendation 1: Better utilize the Department of Commerce and Small Business Administration

The Department of Commerce (DOC) and the Small Business Administration (SBA) are positioned to play an outsized role in engaging with SMEs working in competitive sectors.

Making Use of Regional Offices to Educate SMEs on African Opportunities

The DOC and SBA have over a hundred offices around the country that offer training and business development expertise to entrepreneurs and companies. There are also regional US export assistance centers (USEACs), staffed by DOC and SBA (among other agencies) employees who assist SMEs in competing globally.36“US Export Assistance Center,” US Small Business Administration, https://www.sba.gov/tools/local-assistance/eac. Regional and district offices and USEACs do not necessarily specialize in Africa; they serve customers with all types of interests, and staffers’ portfolios often cover many sectors and geographies.

USEAC staff often lack the incentives and education to make them effective in promoting American competitiveness vis-à-vis the African market opportunity. An internal roadshow targeting USEAC staff could be helpful in a broad education effort. It is equally—if not more—imperative that staff have the key performance indicators in place that allow them to dedicate time to African opportunities, which may not guarantee the same export volume as more developed markets in the short term.37USEAC employees have to report export sales made because of their efforts (not ones in the works or that may take longer to come to fruition). They then are judged relative to overall numbers. Because African markets are small relative to those in Mexico or Canada or Asia, they fail to get adequate USEAC attention. “USEACs Are Meeting Client Needs, but Better Management Oversight Is Needed,” International Trade Administration, September 2004, https://www.oig.doc.gov/oigpublications/ipe-16728.pdf.

Moving Africa-Focused Events Outside of Washington

Ensuring that staff at the DOC’s and the SBA’s regional and district offices are invited to US-Africa business conferences would provide them with easier access to information they can use to bring Africa-focused opportunities to their constituents.

These events—the African Growth and Opportunity Act Forum, US Africa Business Forum, and others—are usually held in Washington, DC, or New York, but moving them around each year would make them even more regionally accessible and generate interest among regional business communities. Senator Chris Coons’ “Opportunity: Africa” conference, held every year in Wilmington, Delaware, is a good example of a regionally scheduled forum that helps generate interest in and educate SMEs about African markets.

Leveraging the DOC and SBA Web Presence

By curating publicly available analysis and how-to’s on doing business in African markets from partners such as the World Bank, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and consulting firms, DOC and SBA can cost effectively reach a greater number of SMEs with much-needed information. The SBA website is a good place to start, because it already provides similar materials for other subjects in its online learning center. The International Trade Administration’s Doing Business in Africa program’s website provides one example of a pamphlet that already exists and can be used as a model.38“Doing Business in Africa,” US Department of Commerce, http://trade.gov/dbia/brochure.pdf.

Recommendation 2: Fund the US EXIM Bank, OPIC, USTDA, and MCC

The Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM), the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), and the US Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) support US companies in foreign markets. Although it is focused on development rather than on corporate interests, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) also has the potential to play a role in advancing US business interests abroad through its procurement policies.

The 2018 budget blueprint that the White House submitted to Congress includes funding restrictions and reductions for OPIC and the USTDA.39“America First: A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again,” The White House Office of Management and Budget, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/2018_blueprint.pdf. It does not explicitly mention EXIM, and the White House has yet to make final funding recommendations for that agency. However, President Donald Trump hinted at restricting its funding during his campaign.40Megan Cassella and Zachary Warmbrodt, “Trump Scrambles Ex-Im Bank Politics,” Politico, April 21, 2017, http://www.politico.com/story/2017/04/21/trump-ex-im-bank-politics-237455. The MCC also escaped mention in the budget blueprint, so it is unclear how it will be affected. OPIC and MCC do most of their business in African countries.

Funding these agencies is vital. Instead of “corporate welfare,”41Marilyn Geewax, “Export-Import Bank Debate: ‘Retreat from Sanity’ or End of Corporate Welfare?” NPR, October 29, 2015, http://www.npr.org/2015/10/29/452618948/export-import-bank-debate-retreat-from-sanity-or-end-of-corporate-welfare; Office of Representative Jeb Hensarling, “Hensarling Statement on Ex-Im Bank Vote,” US House of Representatives, October 27, 2015, http://hensarling.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/hensarling-statement-on-ex-im-bank-vote. EXIM Bank, OPIC, the USTDA, and MCC should be viewed as pillars of support for American competitiveness. That said, the agencies should be subjected to continued pressure to enhance effectiveness and efficacy in working with SMEs. Using US competitiveness as a key focus will help the agencies coordinate and maximize return on taxpayers’ investment.

The Overseas Private Investment Corporation

OPIC is a profit-making entity in the US government: its profits allow it to operate at no cost to the US taxpayer and, because it generates more inflows than outflows, it adds money to the US Treasury.42“Congressional Budget Justification,” Overseas Private Investment Corporation, 2016, https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/files/20150309-opic-cbj-final.pdf. In 2014, OPIC returned $358 million to the budget, marking over three decades of being budget-positive. OPIC provides concessional debt financing to companies and private equity funds working in African markets and political risk insurance. The agency plugs a market gap by providing these products to SMEs under terms that would otherwise be unavailable from non-governmental providers.

To ensure that small businesses know about OPIC and the opportunities it can provide, the agency created an outreach program called Expanding Horizons, which runs workshops around the country to explain OPIC and its services.43“Outreach Events for American Small Businesses,” Overseas Private Investment Corporation, https://www.opic.gov/outreach-events/overview. Expanding such outreach and including private sector presenters who have been successful in African markets could defray costs and make the initiative even more effective.

The US Trade and Development Agency

USTDA supports exports to African markets in two ways—by financing feasibility studies for projects and by coordinating trade missions. USTDA regularly brings foreign buyers to the US sectoral trade shows to see and understand American products. For businesses that would otherwise not have the resources to go on business development trips but would like to enter new markets abroad, USTDA can be a critical partner.

Return on investment in USTDA programming has been growing; from 2008 to 2016, the agency went from generating $35 in US exports for every $1 it spent on project development and programs to generating $85.44“US Trade and Development Agency Achieves Record Return on Investment in Fiscal Year 2016,” USTDA, October 3, 2016, https://www.ustda.gov/news/press-releases/2016/us-trade-and-development-agency-achieves-record-return-investment-fiscal. Given US competitiveness in the service sector, USTDA should put a greater emphasis on initiatives that match US companies in design, engineering, and other professional services to African opportunities.

The Export-Import Bank of the United States

EXIM, responsible for trade finance, has tended to be heavily skewed to large US companies: in 2014, the top ten export beneficiaries used 76 percent of the agency’s total financial assistance.45Veronique de Rugy, “The Biggest Beneficiaries of the Ex-Im Bank,” Mercatus Center, April 29, 2014, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/biggest-beneficiaries-ex-im-bank?429141155. In 2016, there was slightly more balance: EXIM Bank used 53 percent of its loan, guarantee, and insurance authority for SMEs. However, that represented 90 percent of total transactions by volume—47 percent of the funds disbursed went to 10 percent of the companies using EXIM.46“Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Results of Operations and Financial Condition,” Export-Import Bank of the United States, 2016, http://www.exim.gov/sites/default/files/reports/annual/FY16%20MD%2BA.pdf. This disparity, stemming from the expense of large exports such as Boeing planes, has given rise to significant criticism of the agency.

Since 2015, EXIM has been limited in its ability to approve financial packages over $10 million—larger packages require a board vote and the board currently lacks a quorum.47Shayerah Ilias Akhtar, David Carpenter, Grant Driessen, and Julia Taylor, “Export-Import Bank: Frequently Asked Questions,” Congressional Research Service, April 13, 2016, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43671.pdf. Congressional critics have imposed the ceiling and refused to approve additional board members to force greater SME lending. Such punitive measures in an era of political uncertainty are unlikely to be effective. Helping SMEs in competitive sectors export to African markets is one way for EXIM to increase its small business portfolio and work around the $10 million limit.

One of the best ways for EXIM to serve more SMEs is by expanding its Regional Export Promotion Program (REPP), which currently operates in twenty-nine US states. Through REPP, which finds local and state entities who want to partner with EXIM to promote export opportunities, the agency can provide resources to small businesses in locales that might not otherwise have easy access to Africa-focused business assistance. Examples of REPP participants include chambers of commerce, city councils, and state-level small business development centers.48For specific examples, see “Regional Export Promotion Program,” Export-Import Bank of the United States, http://www.exim.gov/tools-for-exporters/repp. Participants agree to provide ten qualified exporter referrals and conduct three export-related events each year, and EXIM provides the associated materials and support.49“Current REPP Members,” Export-Import Bank of the United States, http://www.exim.gov/who-we-serve/regional-export-promotion-program/current-repp-members. Expanding the program in currently unrepresented states would certainly help draw more SMEs to EXIM, which in turn would help EXIM’s standing in Washington.

The Millennium Challenge Corporation

MCC is significantly different than EXIM, USTDA, and OPIC in its aims and operations, but it is no less important to helping open African markets to US businesses. MCC gives grants to developing countries that prove good governance. The grants are executed through compacts signed with governments, usually covering large infrastructure projects. Because of the project-based nature of the grant, the recipient government procures a full range of products and services.

MCC is now working to ensure that more US companies, including SMEs, are aware of these procurement opportunities; historically, a significant amount has been awarded to non-US firms. The agency has created a public-private partnership platform and relationship management system, and has hosted investment roadshows that showcase compact programs.50“Leveraging Partnerships,” Millennium Challenge Corporation, https://www.mcc.gov/resources/story/story-ar-2016-leveraging-partnerships.

While these efforts have yielded some progress, MCC could become an unmatched vector of success in introducing US companies to African markets by changing the terms of recipient country procurement processes. Currently, MCC policies prohibit government-owned enterprises in compact countries from bidding on procurement contracts but otherwise have no other mandated preferences for US or non-US firms.51Millennium Challenge Corporation, Ten Reasons to Do Business with Millennium Challenge Corporation, Fact Sheet, 2016, http://2016.export.gov/california/build/groups/public/@eg_us_ca/documents/webcontent/eg_us_ca_091674.pdf. To maintain flexibility for the recipient government while balancing the need to support US firms, MCC should follow OPIC’s “US-Nexus” system, in which firms competing in the procurement process must have some American element in the bid, be it US shareholders, technical partners, board members, or subcontractors.52OPIC’s definition of “US-Nexus” is the following: “Any recipient of a Downstream must be: (i) organized in the U.S. with at least 25 percent ownership directly or indirectly by US citizens (green card holders); or (ii) organized outside of the U.S. with majority (greater than 50 percent) ownership directly or indirectly by US citizens (or green card holders).” See Overseas Private Investment Corporation, Call for Proposals, https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/files/040313-callforproposals.pdf. The nexus approach would give US SMEs a more structured entry point into African markets.

To make it easier for US firms looking to become involved in MCC compact procurement processes, MCC should also create a list of vetted American companies in key sectors of competitiveness. Once approved on the list, firms can be fast-tracked into procurement processes in all compact countries. Such a pre-vetted list would reduce the red-tape cost faced by US companies and make it easier for African partners to meet the US nexus requirement.

Recommendation 3: use government convening power to create industry roundtables in areas of competitiveness

Hosting sector-focused roundtables that regularly bring stakeholders together would create a shared knowledge base, foster collaborations, and solve common problems. By committing high-level time and energy to an industry dialogue, government agencies would be able to effectively link businesses working in sectors in which the United States has a competitive advantage to opportunities in African markets. This approach differs from the Barack Obama administration’s Doing Business in Africa (DBIA) initiative in its sectoral focus and narrow mandate.

To capitalize on the United States’ strength in finance, for example, OPIC or the Private Capital Group at USAID should partner with leading financial firms to launch a US-Africa Financial Inclusion Roundtable that would bring together American expertise in banking technologies, insurance products, venture capital, and financial security and match market opportunities with willing corporate partners. The Roundtable would meet twice annually on the margins of global finance events such as the Milken Institute Global Conference or World Bank Annual Meetings. Similar roundtables could be created in other areas of competitive advantage—agricultural technology, renewable energy, and creative industries. Each would contribute to US export growth, partnerships between US and African companies, and the diversification of African economies.

Conclusion

US commercial participation in African markets is still evolving and the rapid rate of change in African markets calls for continued innovation. Competition from Chinese and other foreign firms can be expected to intensify given that 70 percent of future growth will come from emerging markets.53The World in 2050: How will the global economic order change?, pwc, February 2017, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/assets/pwc-world-in-2050-slide-pack-feb-2017.pdf

US strategy, therefore, should focus on exploiting areas of competitive advantage to create jobs domestically and promote stability and security in African markets through economic development. Winning in the global market of the future will require ceding some battlegrounds to better-suited players while focusing efforts in the arenas in which success is most likely.

It is time for the narrative around Chinese commercial interests in Africa and the required US response to become more nuanced and focused. Strategic prioritization and buy-in from public and private-sector entities is key to working in a resource-constrained environment to unlock the American competitive edge, broaden and deepen US-Africa commercial relations, and maximize the benefits to US businesses and the American people.

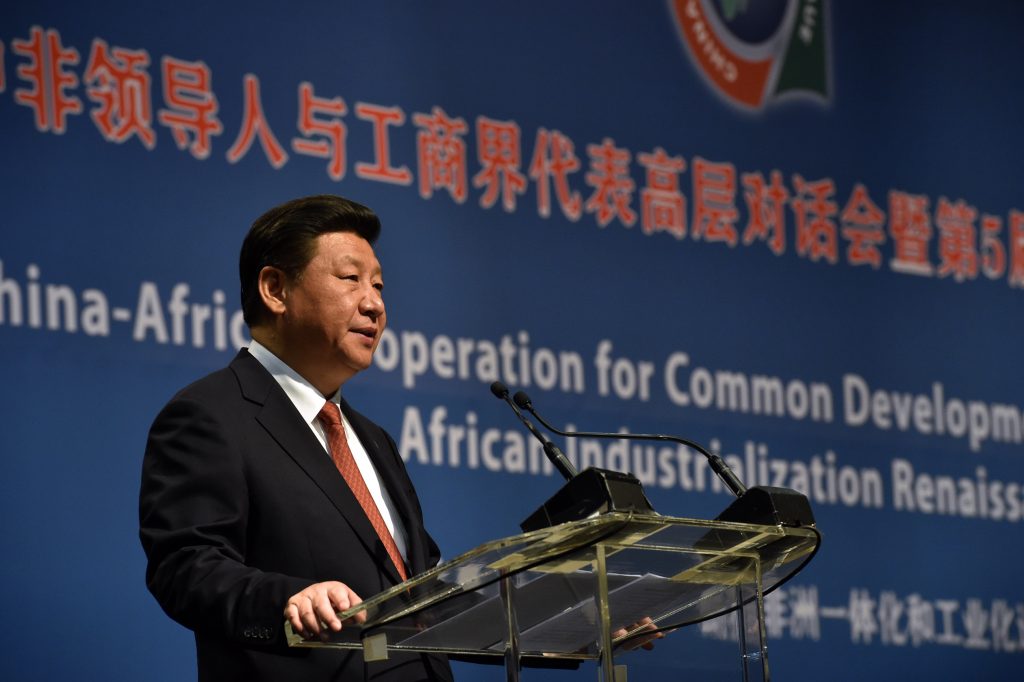

Image: President Xi Jinping of China addresses the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Business Summit, in Johannesburg, South Africa. Established in 2000, the Summit, which takes place every three years, facilitates large-scale investment deals between China and Africa. Photo credit: Republic of South Africa/Flickr.