During the current whole-of-government effort to address US national security vulnerabilities in critical mineral supply chains, the Donald Trump administration is overlooking a major asset in the US commercial policy toolbox—the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). In recent years, the MCC has fallen into the shadows of more high-profile US development finance tools such as the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and the US Export-Import Bank (Eximbank). And reports this week indicate that the administration is planning to shutter the MCC entirely. That would be short-sighted. For an administration focused on aligning foreign aid with core strategic interests, particularly under an “America First” doctrine, the MCC represents an underutilized asset. Unlike other agencies such as the DFC and Eximbank, the MCC’s design—authorized by the bipartisan Millennium Challenge Act of 2003 (MCA 2003)—offers immediate, flexible, and large-scale grant capital that can be deployed immediately to advance US strategic priorities, without the need for congressional reauthorization or additional legislative action.

One of the most immediate opportunities for the Trump administration lies in deploying MCC resources to execute and accelerate a US-Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) critical minerals partnership currently under discussion. As the global race for cobalt, copper, and other energy transition minerals intensifies, China continues to dominate global upstream and midstream processing. The MCC’s country compact model and its authority to engage in regional deals can be reimagined to secure US access to mining opportunities, support US companies in their investment plans, develop necessary energy and transport infrastructure, and advance the regulatory reforms needed to give US companies greater confidence in investing in the Central African region. This can all be done without new legislation. Now is the time to redesign MCC’s operations so it can become a core pillar of a strategic, security-aligned America First foreign policy; failing to leverage this tool would be a strategic oversight.

The MCC: A “big push” development effort

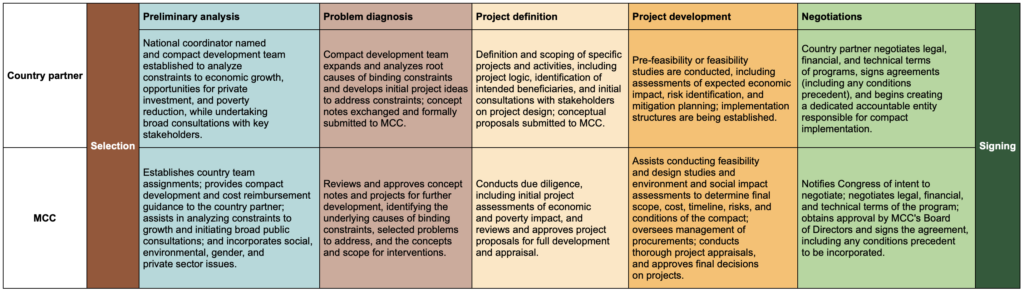

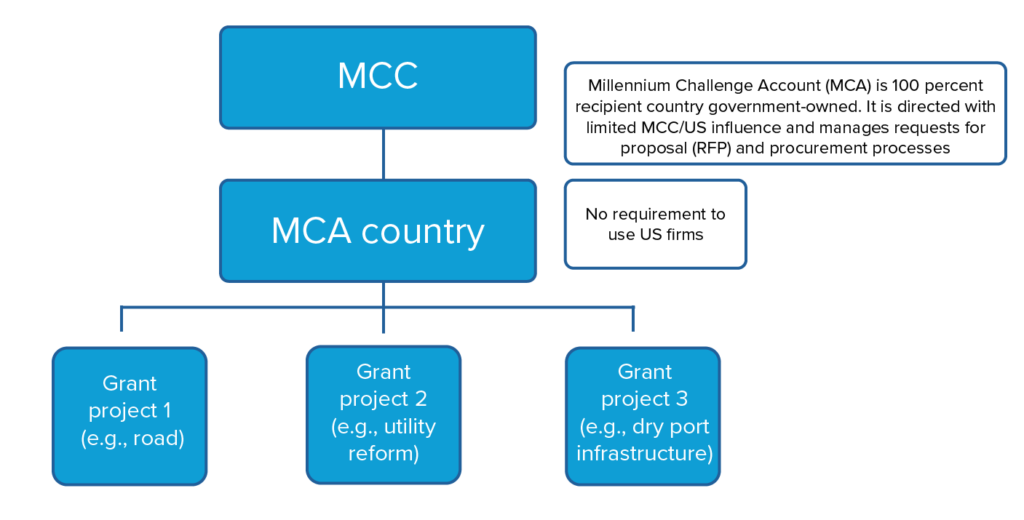

The MCC was established in 2004 through the MCA 2003. Inspired by the Marshall Plan, it was created with a bold vision: to deliver transformative, large-scale development aid to countries that demonstrate a commitment to democratic governance, sound economic policies, and investment in their people. Distinct from traditional United States Agency for International Development (USAID) programming, the MCC’s model to date has focused on large five-year grants negotiated on a bilateral basis between the United States and recipient countries. These five-year agreements, known as “compacts,” can range from $100 million to $700 million, with the average being $350 million. These compacts fund large-scale infrastructure, education, and policy reform projects in select low- and lower-middle-income countries, and can take years to negotiate given the many steps involved (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows how MCC compacts are structured.

Figure 1. From selection to signing: The MCC’s multi-year compact development at a glance

Figure 2. The MCC compact structure

At its core, the MCC has operated as a development assistance program based on an aid-based philosophy, seeking to advance poverty reduction, access to services, and governance improvements in foreign countries. As of January 2025, the MCC had signed forty-five compacts with twenty-nine countries, with many nations signing more than one compact after the completion of the first five-year period. More than 80 percent of the countries supported by the MCC are located in Africa. Historically, countries became eligible for MCC compacts by scoring high on a complex set of twenty indicators (measured by third parties), covering areas such as political rights to immunization rates to land rights to fiscal policy and conservation. In 2018, the MCC received the right to enter into regional compacts to advance cross-border infrastructure and economic development projects that support trade corridors, regional power pools, and customs harmonization. However, only one regional compact has been signed to date.

As the number of eligible countries based on the MCC scorecard has decreased over time, the MCC was able to award threshold programs, which were smaller grants (of one to three years, averaging $20 million to $40 million) focused on helping countries address lagging scores on some of the eligibility indicators. Additionally, the MCC Candidate Country Reform Act, passed as part of the fiscal year 2025 National Defense Authorization Act, expanded the pool of eligible countries to include upper-middle-income countries.

What sets the MCC apart from the DFC and the Eximbank?

While the DFC and Eximbank play important roles in US foreign economic engagement, their tools and mandates differ fundamentally from those of the MCC. The DFC provides loans, equity, and political risk insurance. And while it has mobilized billions in private capital, it is limited by its requirement to generate a return on investment. Similarly, the Eximbank supports US exports through loan guarantees and insurance products but cannot invest in upstream development or non-commercial infrastructure. In contrast, the MCC provides flexible grant capital—an asset class that offers strategic advantages for the United States when competing with China’s state-backed investments and concessional financing.

In the case of critical minerals, this access to untied, large-scale grant capital means the MCC can support essential early-stage project development, including feasibility studies for mining projects, and can enable infrastructure and policy reforms in ways that commercial or quasi-commercial institutions cannot. For example, in the mining sector, MCC funds can help finance roads, rail, and power infrastructure essential to project bankability—thus paving the way for US private investors and DFC-backed investments to follow. Furthermore, the MCC, which has deep experience working with governments, can directly fund regulatory improvements and workforce development—areas that would be off-limits for the DFC or Eximbank. In the context of critical minerals that are needed for long-term US national and economic security, the MCC’s tools are indispensable.

The Trump administration is considering folding the MCC into the DFC—or even shutting down the agency entirely—in an effort to streamline and simplify the tools of US economic statecraft. While this might work in the long run, it would be a mistake in the short term. Due to significant differences in operational frameworks between the MCC and DFC, maintaining the MCC as an independent entity is critical to deploying the powers discussed above. Specifically, under current Office of Management and Budget (OMB) scoring rules, DFC equity investments are treated similarly to grants—scored on a one-to-one basis, which limits the DFC’s ability to expand equity initiatives without substantial new congressional appropriations. Integrating MCC grant resources into the DFC before DFC reauthorization legislation is passed, which may resolve the equity scoring issue, could lead to the DFC prioritizing the use of such funds for equity rather than grants. While equity is important and the DFC’s equity capacity should be expanded, the MCC’s flexible grant-making capacity should be preserved and leveraged to significantly de-risk projects that are of strategic importance to the United States.

MCC 1.0 vs. MCC 2.0

In the Trump administration’s ongoing transformation of US foreign assistance and commercial diplomacy architecture, rather than closing the agency altogether, there is an opportunity to use the MCC differently—to create an MCC 2.0 that will allow for the strategic deployment of US economic statecraft.

A reformed MCC—one that loosens eligibility requirements and speeds up compact development while still focusing on critical infrastructure development—would greatly benefit partner countries, particularly in Africa. With annual infrastructure needs exceeding $130 billion, African countries are actively seeking partners capable of mobilizing large-scale private investment responding quickly to the demands of their young and growing populations. The MCC can be redesigned to operate at the nexus of both African and US national interests.

Using the MCC to counter Chinese dominance in critical mineral supply chains

By simply changing how the MCC operates within its legislative mandate, as defined by the MCA 2003, the Trump administration can access a pool of flexible capital that can be redirected to shape critical mineral supply chains in ways that enhance US national security. The following points illustrate key areas of flexibility:

- Country eligibility does not need to be defined through complex scorecards. Countries can be determined as eligible by the MCC board if they show adequate commitment to democratic governance, economic freedom, and investing in women and children (Section 607 MCA 2003). A board decision approach will dramatically reduce the time needed to negotiate compacts. The methodology can be changed each fiscal year with notice to Congress (Section 608.b.2.).

- Compact countries are asked to make contributions relevant to meeting the objectives of the compact (Section 609.b.2). These contributions could take the form of mineral resources or rights, as is being discussed between the Trump administration and the government of Ukraine.

- The MCC can pay for expert consultants or legal counsel on behalf of eligible countries to fast-track compact negotiations with the MCC (Section 609.g).

- The MCC can award subsequent and concurrent compacts (for example, regional compacts) to countries so that long-term planning is possible beyond the initial five-year compact (Sections 609.j, 609.k, and 609.l).

- MCC grants can be awarded (within the framework of a compact) to national governments, subnational governments, nongovernmental organizations, or private companies (Section 605.c).

- The MCC can make other grants to individuals, firms, or governments deemed necessary for the functioning of the corporation (Section 614.a.3).

- The MCC can make grants of up to five million dollars to universities (both foreign and US universities) for relevant data (Section 614.g). China has long supported the geology departments of African universities in its effort to access relevant data on mining opportunities and build a network of local experts. Under this provision of the MCA 2003, the MCC would be able to counter that influence and help build the skilled workforce needed for resilient mining industries.

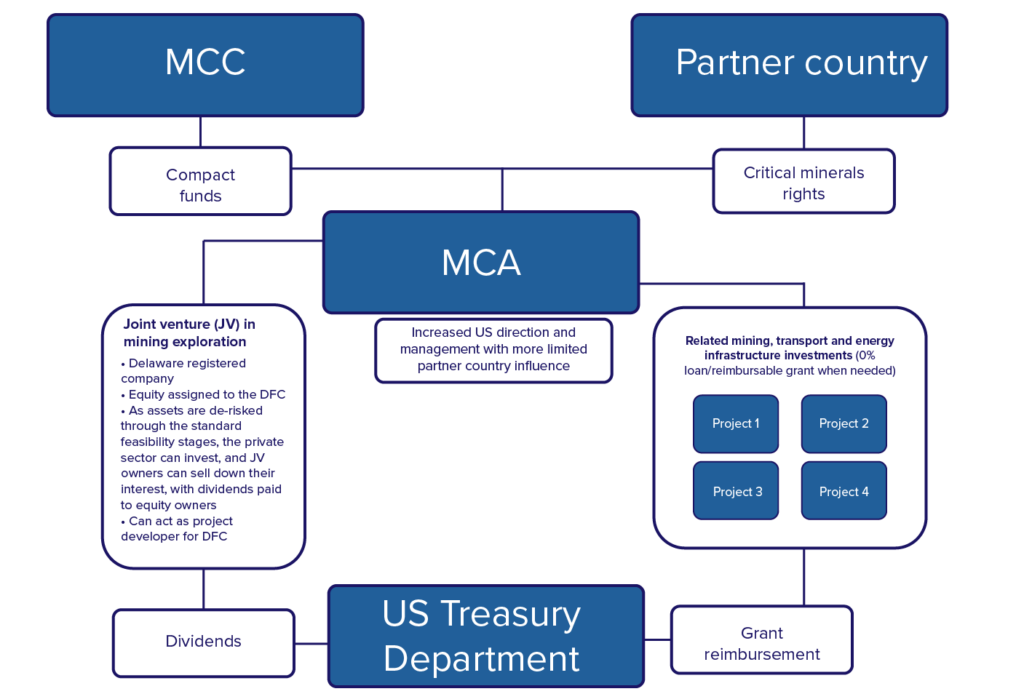

In rethinking the MCC’s operations, large pools of grant resources could be strategically directed toward building US partnerships in the mining, processing, and manufacturing of critical minerals. A generic compact could be signed with a country such as the DRC within three months of determining eligibility (in accordance with the 2023 MCA’s congressional notification requirements). Subsequently, projects could be developed and funded on a rolling basis. Figure 3 shows a potential structure for a compact focused on critical minerals.

Figure 3. The MCC 2.0: An investment partnership model

Under this new MCC 2.0 compact structure, the United States and another country could form a joint venture (JV) focused on early-stage exploration. The JV would acquire exploration licenses from the country at no charge but would be required to advance licenses from exploration to the pre-feasibility stage within four years. This alignment of interests would help fast-track the permitting and government engagement around the deals. Once assets have been de-risked enough to generate interest from private investors, the JV company would sell down its interest. The JV would operate with the highest levels of transparency, good corporate governance, and data sharing, employing the latest technologies to more accurately assess mining opportunities.

Equity ownership of the JV could be assigned by the MCC to the DFC (which can legally have equity) or a US trust account and could also include subnational government or community ownership. The MCC would seed the JV with initial equity—perhaps $50 million of a $400-million compact—but subsequent rounds could be raised through capital market strategies.

The remaining compact funds would be reserved for the infrastructure necessary for resilient and cost-competitive supply chains—including transport and energy projects. In Zambia and the DRC, the biggest constraint to expanding copper production is the lack of energy resources. The Congolese mining sector faces an energy deficit of between 500 megawatts (MW) and 1,000 MW. All procurements related to energy and mining-sector investments will incorporate a preference for US companies (an automatic 20-percent bonus point allocation by the Technical Evaluation Panel). The MCC will actively market projects to US companies through public relations, marketing efforts, and regular roadshows, and will provide support US companies in due diligence and vetting potential local partners.

Launch MCC 2.0 as part of Trump’s first one hundred days

As Trump’s first one hundred days draw to a close, there is still time for action in regard to the MCC. Instead of shutting down the agency, the Trump administration should nominate a chief executive officer for the MCC without delay and, while confirmation is pending in the Senate, the administration should run the MCC through a beachhead team, as was done at the Eximbank since January. The MCC 2.0 model can be applied immediately to the DRC deal under consideration or to mining resource-rich countries familiar with the MCC, such as Zambia and Tanzania. The United States is working to turn around decades of policies that ceded strategic advantage in critical value chains to China. The MCC should be seen as a vital part of that effort.

About the author

Aubrey Hruby is a senior adviser and senior fellow at the Africa Center at the Atlantic Council and leads the center’s Critical Minerals Task Force.

Related content

Explore the program

The Africa Center works to promote dynamic geopolitical partnerships with African states and to redirect US and European policy priorities toward strengthening security and bolstering economic growth and prosperity on the continent.

Image: Malawi's President Lazarus McCarthy Chakwera shakes hands with Millennium Challenge Corporation CEO Alice Albright as they celebrate the signing of the Malawi Transport and Land Compact with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Malawian Finance and Economic Affairs Minister Sosten Alfred Gwengwe, at the State Department in Washington, September 28, 2022. Kevin Wolf/Pool via REUTERS