Democracy in the crosshairs: How political money laundering threatens the democratic process

International political dark money is a crucial, but little-understood, part of a toolkit of techniques that have been used, with accelerating intensity, to influence major liberal democracies and transition states over the last decade. Using three concrete case studies, this report outlines the active threat of dark money in the context of hostile powers’ subversion operations, explains how current legislation and enforcement mechanisms are inadequate, and proposes a “layered defense.”

Contents

Executive summary

This report outlines how hostile states use “dark money” to subvert liberal democracies’ political systems. It argues that this poses a grave threat to the integrity of democratic systems and, indeed, to national security itself.

Hitherto, public concern about foreign interference in Western democracies has mainly focused on the use of fake news and social media bots. This paper is only tangentially concerned with information warfare; instead, it focuses on the question of whether existing electoral-finance legislation and enforcement are an invitation to subversion by foreign actors. Mechanisms to verify who is funding political parties are grossly obsolete; electoral laws in most Western democracies almost never place the onus on the donor to prove the source of their wealth, instead taking them at their word that they are not acting as an agent for someone else.

This paper argues for urgent and major reform of electoral rules in liberal democracies. This is a new era, in which Putinist Russia is making up for its relative military and economic weakness by undermining liberal democracies, using aggressive internal-destabilization techniques. This is not only about swinging elections or referendums, but about sponsoring parties of the far left and far right, which issue divisive rhetoric pitting citizens against each other, while rendering normal government increasingly difficult.

Three case studies demonstrate these points:

The €20-€30 million in media spending in support of German far-right political party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in 2016-2018. This money came from an opaque German association, which then transferred the money to a Swiss public relations company, which then spent the funds in Germany.

Arron Banks, who backed Leave.eu and other pro-Leave groups prior to the UK’s 2016 Brexit referendum. He made the largest-ever political donation in British history. When challenged, Banks merely stated that the money came from his own bank account, despite well-founded doubts over the extent of his wealth, and has offered widely conflicting accounts of important financial transactions.

The increasing importance of small donations under the $200 reporting threshold in US elections. A rule intended to allow citizens to make small donations anonymously is now enabling hundreds of millions of dollars to be funneled into campaign coffers with no clue to its sources. The advent of cashless payment cards, cryptocurrency, and technology to allow automated mass donations has turned this rule into an open invitation to political money laundering.

The first case study covers the opaque structures channeling millions of euros in support for Germany’s Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) party. Across state and national elections in Germany, the Rights and Freedom Club has plowed between €20 million and €30 million into billboards, rallies, online advertising, and even its own newspaper. This amount far outstrips AfD’s own spending, giving the party a substantial advantage in German elections. The advertising urges the electorate to vote for AfD candidates—but, because the Rights and Freedom Club is not running any candidates itself, it is not required to declare the origin of the money. It could well be that this money is coming from purely legitimate sources, but there is no way to tell.

Second, there is the conundrum of how the most generous donor in British political history, Arron Banks, could have afforded the donations he made to the pro-Brexit campaign. He has stated that his wealth is anywhere between £100 million and £250 million, but investigations have since shown this to be greatly overstated. Just as Banks began giving money to British politics in 2014, his existing businesses had significant liabilities. It has also come to light that Banks was offered lucrative business deals in and related to Russia in the lead-up to the June 2016 referendum. There is no evidence that he acted on any of these offers, but the fact that at least one Russian intelligence officer, as well as an ambassador, was interested in offering deals to Banks is suspicious in itself.

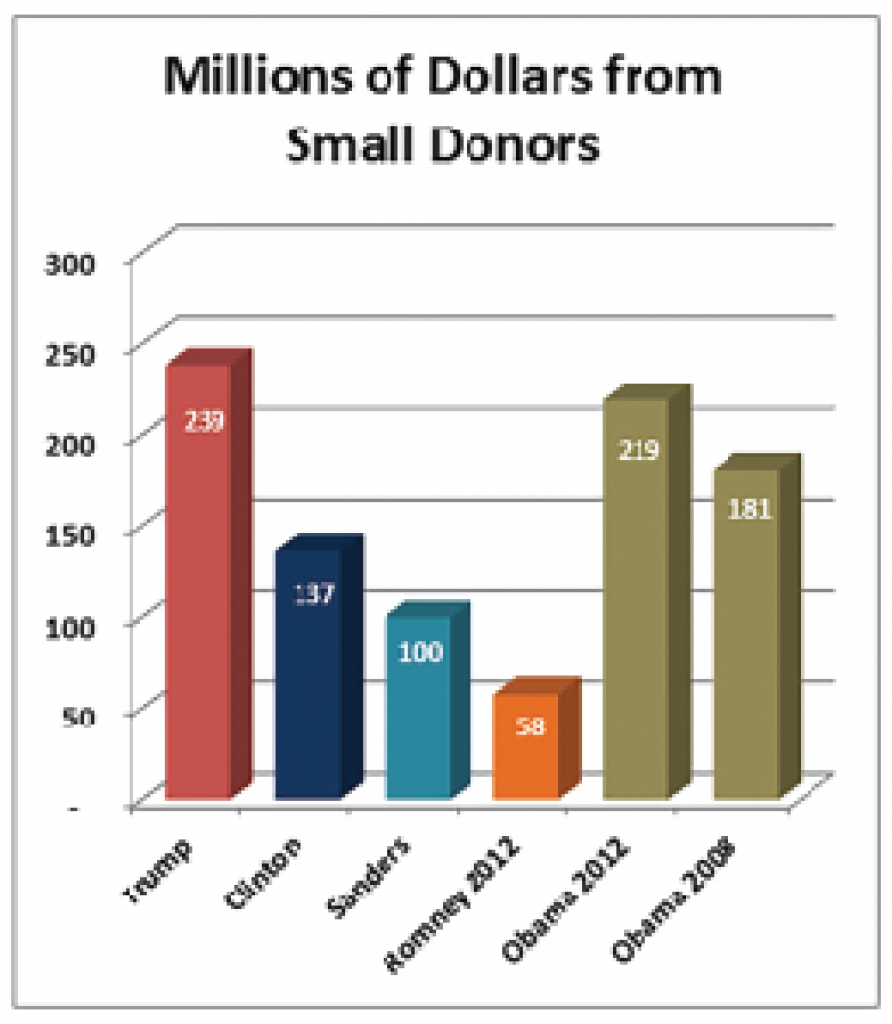

Finally, the third case study concerns Donald Trump and small donations, below the $200 threshold at which donors must be identified under US federal law. Trump quietly raised approximately two-thirds of his campaign funds through donations under the $200 mark, dramatically outstripping his opponents when it came to the overall proportion of money raised from small donations. At present, there is no way to know whether all of these donations really came from millions of supporters, or, in an era of cryptocurrency and anonymized online payments, if this money came from illicit sources.

The real burden should fall on donors: if they want to contribute money to politics in a given country, their wealth must be clearly explained, through publications of tax returns or other means, and it should have been already taxed in the jurisdiction where the donation is made. Illicit collaborations between nominally separate, but effectively conjoined, political organizations must end. Finally, truly punitive measures and effective joint-investigation techniques must be available to law enforcement and the security services.

Introduction

This report outlines how hostile states use “dark money” to subvert liberal democracies’ political systems. Armored divisions or aircraft carriers are redundant if an adversary can secure direct influence at the national-leadership level.

International political dark money is a crucial, but little-understood, part of a toolkit of techniques that have been used, with accelerating intensity, to influence major liberal democracies and transition states over the last decade. At the political level, other techniques include hacking, “doxing,”1“The distribution of someone’s personal information across the internet against their will,” Lily Hay Newman, “What to Do If You’re Being Doxed,” Wired, December 09, 2017, Accessed September 18, 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/what-do-to-if-you-are-being-doxed/. improper collection of personal data, interfering with voting machines, the use of botnets, and the spreading of disinformation (now often called “fake news”). At the more aggressive end of the spectrum, the actions influence measures include infiltration by provocateurs and special forces, cyberattacks on infrastructure, assassinations, and finally, full-scale military action.2Molly K. McKew, “The Gerasimov Doctrine,” Politico, September/October 2017, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/09/05/gerasimov-doctrine-russia-foreign-policy-215538.

“Dark money,” as set out in Jane Mayer’s eponymous book, is by now quite well understood.3Jane Mayer, Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right (New York: Anchor, 2017). While Mayer’s book described domestic actors aiming to influence the US political scene, the types of electoral chicanery described in the book—“astroturfing,” the creation of apparently diverse groups that actually have a single origin, the use of foundations, and the use of political action committees (PACs) and other nominally distinct outfits—have also been studied, developed, and refined by hostile states with substantial resources at their disposal.

What sets international political money laundering apart from those other techniques is that it is difficult for domestic politicians and policymakers to come to terms with: hostile states are exploiting exactly the same loopholes those leaders themselves have used for decades. Few democratic leaders will balk at establishing better defenses against electronic attacks or filtering out mass disinformation. Campaign donations, however, are different, because stiffening regulation will limit parties’ fundraising options. This paper argues that this is a price well worth paying.

Using three concrete case studies, this report outlines the active threat of dark money in the context of hostile powers’ subversion operations, explains how current legislation and enforcement mechanisms are inadequate, and proposes a “layered defense.”

The threat

Political money laundering cases seen and suspected in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Australia, and other states are not fundamentally distinct from the challenges of standard campaign-finance regulation. But, when weaponized by hostile states with billions of dollars in offshore centers and large, efficient intelligence services, money laundering poses a grave threat to democratic integrity. This includes:

- the use of opaque offshore centers to obscure funds’ origins

- the use of fabricated business transactions to transfer funds or covertly enrich individuals

- the advent of cryptocurrencies and cashless cards whose origins are untraceable

- the co-opting of “straw men” who count as permissible donors (generally not seen in domestic cases)

- the use of linked (but deniable) anonymous organizations to circumvent spending limits

- the rise of movements, super PACS, and parallel campaign funds that evade regulation

- the use of clubs, companies, and councils as donors as a way to avoid disclosure

- the establishment or subversion of think tanks, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and other influence nodes, and associated funding

Hostile states run these operations through their intelligence services, and will always try to maintain plausible deniability. While “follow the money” is a mantra of investigative journalism, in most cases there will never be a formal, documented link to the funding states. Rather, they will co-opt wealthy nationals—from their own and other states—creating an additional layer of deniability.

Case studies

Each of the three recent case studies below is drawn from a different country, but they have a common lack of transparency. No wrongdoing is stated or implied in any of the cases. The aim here is simply to show that in each country, tens—or even hundreds—of millions of dollars, euros, and pounds of completely obscure origin have entered the political system.

Case study 1: The Rights and Freedom Club

It has a lengthy name, but the Verein zur Erhaltung der Rechtsstaatlichkeit und Bürgerlichen Freiheiten (or “Rights and Freedom Club”) has a straightforward purpose: telling German voters to support the hard-right Alternative für Deutschland party. Estimates suggest that the Rights and Freedom Club has spent between €20 million and €30 million since March 2016 to sustain huge advertising campaigns in support of AfD candidates at the state and national levels. To put this figure in perspective, the AfD’s total reported income for 2016 was €15.6 million, of which donations counted for just €6 million.4Deutscher Bundestag, “Fundstellenverzeichnis der Rechenschaftsberichte,” August 26, 2016, https://www.bundestag.de/parlament/praesidium/parteienfinanzierung/rechenschaftsberichte/. The funding was raised from anonymous private donors; remarkably, the identities of the club’s donors have never been disclosed. This arrangement is completely legal under German law.

The Rights and Freedom Club firmly denies any formal ties to AfD, saying it is only a verein (club) of activists, and is not running any candidates. This means the club is not subject to the regular campaign-finance rules under which AfD itself must operate, which require donors’ names and addresses to be declared. Similarly, the AfD claims to be a body distinct from the club. The club’s spokesman and chairman, David Bendels, has defended the arrangement, stating that “the donations are made up of a large number of smaller and larger donations. We do not provide information about the amount of the individual donations.”5Hans-Wilhelm Saure, “AfD-Unterstützer-Verein will Gemeinnützigkeit,” Bild, October 13, 2016, https://www.bild.de/politik/inland/alternative-fuer-deutschland/verein-will-gemeinuetzigkeit-48259446.bild.html.

The true spending of the Rights and Freedom Club has only ever been an estimate. For example, some journalists have used data provided by advertising and printing companies to calculate that during the 2017 North Rhine-Westphalia elections, a conservatively estimated €4 million may have been spent on various forms of traditional advertising, direct mail, and street flyers, and might even have included a promotional newspaper written by the Zurich PR firm Goal AG, of which more than 2.5 million copies were printed. However, because the club is not a political party, there is no requirement for it to publish any of its spending.

The mystery of who is behind the donations, and how much the Rights and Freedom Club actually spends, is matched by the way the organization is administered. The club claims to have roughly nine thousand members, yet lacks a physical office.6Von Jürgen Bock, “Die neuen Konservativen” Stuttgarter Nachrichten, December 22, 2016, https://www.stuttgarter-nachrichten.de/inhalt.stuttgarter-verein-will-vordenkerrolle-die-neuen-konservativen.94460f08-d979-429c-a9ee-6beeac7c7f8e.html. A post-office box in Stuttgart is the only physical trace of the club on German soil. Mail is then redirected from there to Goal AG, a political public-relations firm based in Switzerland. The same firm originally designed the Rights and Freedom Club’s branding, slogans, social media campaigns, and website.

“ …Offshore jurisdictions not only facilitate criminal activity and tax evasion, but also hostile intelligence activity.”

Goal AG is run by Alexander Segert, a Swiss political-communications expert. The company has a long history of providing services to the populist Swiss People’s Party (SVP), the Austrian People’s Party (FPÖ), and the Front National in France (recently renamed Rassemblement National).7Guy Chazan, “The Advertising Guru Harnessing Europe’s Immigration Fears,” Financial Times, December 30, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/ce212a22-ce6c-11e6-864f-20dcb35cede2. It also provides marketing services to the Europe of Nations and Freedoms grouping in the European Parliament, which gathers alt-right members under one umbrella.8“Lega Victory at Italian Elections: Times are a-Changing,” ENF, March 16, 2018, https://www.enfgroup-ep.eu. AfD is a member, alongside parties like Matteo Salvini’s Liga Norda in Italy and Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom in the Netherlands. An AfD executive committee member has publicly stated that Goal AG consulted with AfD while undertaking work for the club on a poster campaign in Essen, and possibly in other instances. He later retracted the statement.9“AfD-Spitze in Sorge wegen Vorwurf der illegalen Parteienfinanzierung,” Welt, July 22, 2018, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article179797858/Distanz-zu-Unterstuetzungs-Verein-AfD-Spitze-in-Sorge-wegen-Vorwurf-der-illegalen-Parteienfinanzierung.html.

The political positions taken by the Rights and Freedom Club are almost identical to those of the AfD. The Extrablatt newspaper, which has appeared prior to most of the German state elections, has carried articles that are anti-Chancellor Angela Merkel and blame her for refugee criminality, urging readers to vote AfD.

Since July 2017, the club has published its own newspaper, Deutschland-Kurier—normally online, but also occasionally in print.10Joachim Huber, “’Deutschland-Kurier’ startet in Berlin,” Der Tagesspiegel, July 10, 2017Deutschland Kurier, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/medien/neue-rechtskonservative-wochenzeitung-deutschland-kurier-startet-in-berlin/20029118.html.org. It features a large number of AfD, as well as FPÖ, politicians as its columnists, and has been compared to the United States’ Breitbart.11Thomas Schmelzer, “Eine Mischung aus Breitbart und Bild,” Wirstschafts Woche, July 12, 2017, https://www.wiwo.de/politik/deutschland/deutschland-kurier-eine-mischung-aus-breitbart-und-bild/20053842-all.html. The club also cooperates closely with the conservative Weikersheim Study Centre (SZW), and has recently established a new role for itself as an AfD incubator.12Martin Eimermacher, Christian Fuchs, and Paul Middelhoff, “Ein aktives Netzwerk,” Zeit, November 2, 2017, https://www.zeit.de/2017/45/afd-netzwerk-zeitschriften-stiftungen-verlage/seite-2.

At the Hesse state elections, club Chairman David Bendels “sounded like an AfD politician on the campaign trail,” according to a report in Zeit, whose journalists attended one of his events. He “rails against German Chancellor Angela Merkel,” they reported, “against multiculturalism and the counter-demonstrators, who he calls ‘left-wing fascists,’ who had gathered in front of the bar where he spoke.”13Christian Fuchs and Fritz Zimmermann, “Schatten-Spender,” Zeit, May 13, 2017, https://www.zeit.de/2017/20/afd-finanzierung-verein-nrw-spenden-david-bendels.

At a similar rally ahead of the North Rhine-Westphalia polls, Bendels told two hundred attendees that there was “only one alternative, the AfD!” Alexander Gauland, the AfD’s top candidate for election to the Bundestag, was reportedly present. When approached by reporters, however, Bendels denied any formal connection to AfD.14Ibid.

Similarly, during the Mecklenburg-West Pomerania elections, posters appeared with slogans including “Germany is being destroyed. Now choose AfD,” but AfD’s candidate, Leif Erik-Holm, told the Frankfurter Allgemeine that he had no idea who had paid for them.15Friederike Haupt, “Die geheimen Helfer der AfD,” Frankfurter Allgemeine, August 21, 2016, http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/wahl-in-mecklenburg-vorpommern/afd-erhaelt-wahlunterstuetzung-von-verein-in-mecklenburg-vorpommern-14398142.html.

Germany’s “club” loophole has existed for some time, and AfD is not the first to exploit it. It played a role in the Christian Democratic Union’s (CDU) financing scandal that first broke in 1999, although the illegal channeling of money in that instance went back to the 1970s. The scandal resulted in criminal convictions and lengthy sentences, but the right of independent “supporters” to channel funds from donors to support a particular party, while keeping the donors’ identities secret, has remained.16Peter Kreysler, “Dunkelkammern der Demokratie,” Deutschlandfunk, August 7, 2018, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/populistische-stimmungsmacher-und-ihre-schattenspender.1247.de.html?dram:article_id=420905. It may be the case that otherwise legitimate German donors are using this elaborate method to hide their identities, or they could be foreign actors. During the CDU financing scandal, the money was eventually traced to Saudi Arabia and linked to defense deals.17“Schreiber-Million kam von Thyssen,” Spiegel, October 12, 2000, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/spendenausschuss-schreiber-million-kam-von-thyssen-a-97768.html. Today, one possibility is that the money pouring in to support the AfD originates in Russia.

“ The ‘club’ loophole has existed for some time, and AfD is not the first to exploit it.”

The AfD disputes this, painting itself as a grassroots movement invigorated by traditional donors. Bendels told Focus magazine in December 2016 that the organization had more than eight thousand members, and that “the donors include financiers from the middle-classes and industry, who five or six years ago would have financially supported the CDU or the FDP.”18Hans-Jürgen Moritz, “Ex-CSU-Mann sammelt Geld für AfD-Wahlkampf,” FOCUS, December 17, 2016, https://www.focus.de/magazin/archiv/fakten-fakten-fakten-und-die-menschen-der-woche-ex-csu-mann-sammelt-geld-fuer-afd-wahlkampf_id_6361331.html.

In June 2017, the party’s national leadership came under pressure from federal authorities, and issued a belated and symbolic cease-and-desist letter to the club’s management, asking it to no longer support AfD candidates. Spiegel cited several senior AfD sources, who said that the AfD federal executive had “prohibited the club from using the logo and corporate design of the [AfD].”19“AfD geht gegen eigene Unterstützer vor,” Spiegel, July 21, 2018, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/afd-geht-gegen-eigene-unterstuetzer-vor-a-1219408.html.

The move appears to have been halfhearted. As the letter was being sent, AfD leader Jörg Meuthen said, “At no time have I ever had ties with this club.”20“AfD-Spitze in Sorge wegen Vorwurf der illegalen Parteienfinanzierung.” When presented with an interview he had conducted for a Rights and Freedom Club newsletter, he claimed this had only occurred because the journalists had misrepresented the outlet for which they worked. But, Spiegel discovered that Meuthen’s website happened to be run by the same Swiss PR firm, Goal AG, that also contracted services with the Rights and Freedom Club.21Melanie Amann and Sven Röbel, “Log AfD-Chef Meuthen im ‘Sommerinterview?’” Spiegel, July 23, 2018, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/afd-chef-joerg-meuthen-log-er-im-bezug-auf-anonyme-millionenspender-a-1219693.html. Goal AG also provides services to other senior AfD members, including Marcus Pretzell and Gudio Reil.22Ulrich Müller, “Geheime Millionen und der Verdacht illegaler Parteispenden: 10 Fakten zur intransparenten Wahlkampfhilfe für die AfD,” Lobby Control: Initiative für Transparenz und Demokratie, September 2017, https://www.lobbycontrol.de/wp-content/uploads/Hintergrundpapier_Verdeckte_Wahlhilfe_AfD.pdf. A few days after the cease-and-desist letter was sent, Bendels—chairman of the Rights and Freedom Club—spoke at an event alongside AfD Bundestag member Martin Hohmann and Maximilian Krah, the deputy chairman of AfD’s Saxony branch. The event was an AfD rally.23“AfD-Wahlkampfauftakt im Bürgerhaus Johannesberg mit rund 200 Interessierten,” Osthessen News, July 20, 2018, https://osthessen-news.de/n11594282/afd-wahlkampfauftakt-im-buergerhaus-johannesberg-mit-rund-200-interessierten.html. See picture on top row, last on right.

Civil society and international bodies continue to raise specific concerns about the Rights and Freedom Club, though German authorities have been slow to act. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which observed the 2017 Bundestag elections, noted then that the club was “effectively campaigning on behalf of the AfD,” and stated that “consideration could be given to providing a regulation of any campaigning by third parties.”24OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, Elections to the Federal Parliament (Bundestag) 24 September 2017 OSCE/ODIHR Election Expert Team Final Report (Warsaw: OSCE ODIHR, 2017) https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/germany/358936?download=true. Organizations including the German PR Council and the NGO LobbyKontrol have also admonished the group.25Anna Jikhareva, Jan Jirát, and Kaspar Surber, “Der Auslandseinsatz des SVP-Werbers,” Die Wochenzeitung, May 18, 2017, https://www.woz.ch/1720/exportnationalismus/der-auslandseinsatz-des-svp-werbers.Heidi Bank, “Und die AfD weiß von nichts,” Frankfurter Rundschau, May 11, 2017, http://www.fr.de/wirtschaft/gastwirtschaft/gastwirtschaft-und-die-afd-weiss-von-nichts-a-1276729. One journalist, who had been researching the story for two years, said that he had interviewed more than fifty people about where the money for the club originates, and not a single source could—or would—say.

Case study 2: Arron Banks

The sums of money involved in British politics are far lower than in US politics, but the UK has an established group of wealthy individuals, entrepreneurs, hedge funds, and corporations that donate to all of the main parties. In most cases, it is fairly clear how these donors made their money, and that they can broadly afford to make these donations.

But, more than two years after the Brexit referendum, a serious question about one of these individuals is still outstanding. How could the most generous donor in British political history, the man who provided nearly £10 million in support of the Leave campaign, afford to give such a generous sum?

In November 2017, the UK Electoral Commission opened an investigation into the finances of Arron Banks, the co-founder of Leave.EU, a backer of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), and a close associate of Nigel Farage. The commission wanted to establish whether Better for the Country Ltd, a Banks-controlled entity, “was the true source of donations made to referendum campaigners in its name, or if it was acting as an agent,” and “whether or not Mr. Banks was the true source of loans reported by a referendum campaigner in his name,” as well as “whether any individual facilitated a transaction with a non-qualifying person.”

The investigation was launched after an article on the UK-based website openDemocracy analyzed Banks’ business structures; it asked simply, “How Did Arron Banks Afford Brexit?”26Alastair Sloan and Iain Campbell, “How Did Arron Banks Afford Brexit?” openDemocracy UK, October 19, 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/uk/brexitinc/adam-ramsay/how-did-arron-banks-afford-brexit. Far from the successful businessman he presented himself as, by 2014 Banks had severe financial difficulties in Gibraltar, where he ran an ailing insurance underwriter called Southern Rock. After an investigation by regulators found Banks to have been trading while insolvent for three years, he was asked to restore capital to the business. As of October 2017, he still owed £60.2 million in payments to prop it up.

openDemocracy also found that the sale of an earlier insurance business, Brightside, which he had previously suggested had netted him £145 million, had actually only earned him a pre-tax windfall of £22 million—making his £9.6 million in donations seem implausibly generous.

Banks had also claimed to work for both Warren Buffett and a major UK insurance company, Norwich Union—but, when approached, both said he had not been an employee. Banks had also suggested that his money came from diamond mines in South Africa, and a bank on the Isle of Man in which he held a stake. In fact, both businesses were performing poorly, and not generating anywhere near the liquid cash required to pump millions into British politics.27Ibid.

On the same day the article was published, Labour MP Ben Bradshaw raised the questions it posed in the House of Commons, asking, “Given the widespread public concern over foreign and particularly Russian interference in Western democracies,” would “the government and the Electoral Commission examine the [openDemocracy report] very carefully, and reassure our country that all of the resources spent in the referendum were from permissible sources?”28Ben Bradshaw, “Business of the House: Part of Grenfell Tower—in the House of Commons at 11:15 am on 19th October 2017,” TheyWorkForYou, October 19, 2017, https://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2017-10-19c.1012.3. The New York Times, Guardian, Bloomberg, and other outlets soon picked up the story. Two weeks later, the Electoral Commission announced its investigation, which is ongoing.

The commission faces a significant challenge. It lacks the resources, expertise, and legal powers to conduct an investigation of this sort. Banks has been linked to several secrecy jurisdictions, including the Isle of Man, where the ultimate holding company for his businesses is registered, as well as the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, and the Cayman Islands. He has used variations of his own name to register more than thirty-five companies in the UK alone. Intra-company transactions are a defining feature of his business style, making it hard to work out exactly where his possible wealth sits at any one time.

Banks and his colleagues continue to obfuscate about where the money came from. “I’ll tell you where Arron got his money from,” said Leave.EU’s press officer, Andy Wigmore, in a March 2018 interview:

“About a year before [the referendum], we sold a law firm called NewLaw for £43 million and that money sat in an account and we used it to finance Brexit,” he said, adding that the Electoral Commission was aware of this and that financial records existed proving it.29J. J. Patrick, “‘We Didn’t Really Appreciate the Machinations’—Andy Wigmore: The Brexit Interview,” Byline, March 2, 2018, https://www.byline.com/column/67/article/2073

Scrutiny of this deal subsequently showed that Banks was neither a shareholder nor even a director at the time of sale; in any case, he only ever controlled a tiny stake in NewLaw Legal. Even if he had controlled shares at the time of the sale, the cash offered for the business had only amounted to £24.5 million, meaning Wigmore was greatly exaggerating even that figure.30Helphire Group PLC, “Acquisition of the New Law Group of Companies,” FE Investigate, February 27, 2014, https://www.investegate.co.uk/helphire-group-plc–hhr-/rns/acquisition-of-the-new-law-group-of-companies/201402270700450726B/.

Banks and Wigmore later appeared together in front of a parliamentary committee, and the following exchange took place:

Jo Stevens [Labour MP]

I think, Mr. Wigmore, you have said in interviews that the large donation that you made—Mr. Banks, the source of that income was the sale of NewLaw, a law firm that you were involved in.

Andy Wigmore

I was not involved in NewLaw.

Jo Stevens

Was it Mr. Banks?

Andy Wigmore

Mr. Banks, yes. What would I know about where he came into money? It was a suggestion. I said, “Well, he did sell a law firm.” They were questioning whether or not they had the money. Well, it is public record.

Arron Banks

One of the things I would say on that is there has been a number of reports, I think by OpenDemocracy. They have questioned the source of my wealth. I think that is where that—

Jo Stevens

It is a lot of money that you gave to the referendum and we would be most interested in where it came from.

Arron Banks

I felt very strongly about it. I think that is probably clear. But NewLaw was a personal injury law firm that I set up. It was sold to various shareholders to Helphire for, I think, £36 million, so I think in relation to the questions we have been bombarded with there are random answers.

Jo Stevens

No, I am just interested. I think it was April 2018, Mr. Wigmore, you said that the sale of NewLaw Legal was how money was generated for the referendum.

Andy Wigmore

It would have been as an idea. You talk about Arron Banks’s wealth. I don’t know his true wealth, but if you were asking me, “Does he have any money?” one of my responses would have been, “Well, he just sold a law firm for X.”

Jo Stevens

So we have a misrepresentation, we have something wrong and we have an idea…At the time of the sale, Mr. Banks, you were not a shareholder or a director, were you, of NewLaw Legal?

Arron Banks

It is not a misrepresentation. I was the founder of NewLaw and it was sold.

Jo Stevens

No, I was not talking about that. I was talking about Mr. Wigmore’s previous answer to me. At the time of the sale, Mr. Banks, you were not a shareholder or a director, were you, in NewLaw Legal?

Arron Banks

Yes. I was a shareholder of NewLaw and I received a check for it. [Interruption] Yes, I was.

Jo Stevens

But you were not at the time of sale? You were not at the time of sale, were you?

Arron Banks

No. Ultimately, there was a sale of the company to a company called Helphire. By that stage I was not a shareholder in the business and I had sold my shares prior to that. I was one of the founding shareholders of the business, along with John Gannon and Helen Molyneux, and some others. We were all business partners in it and I had sold my shares of it.31Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, “Oral Evidence: Fake News, HC 363,” House of Commons, June 12, 2018, http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/digital-culture-media-and-sport-committee/fake-news/oral/85344.html.

In other words, Banks admitted that Wigmore’s statement was factually incorrect, but did not offer any alternative explanation. When subsequently invited to do so by the BBC in July 2018, Banks repeatedly refused to explain the source of the funds. Here is a typical excerpt:

Q: You could show us where the money comes from.

A: I told you it’s come from my bank account.

Q: You could show us the companies that have made enough profit to justify it because we certainly can’t see [it].

A: Well, as far as I’m concerned, I’ve done what I had to do.

This year, numerous leaks and disclosures by journalists have shown that Russian state actors were at least interested in enticing Banks in a collaborative effort that might have improved his business prospects.

The offers reported so far were made to Banks before the referendum, and were organized by the Russian ambassador in London and two intelligence officers. At least one of these officers was expelled after the Skripal attack in March 2018. The offers included:

- an opportunity to take part in a gold-mining endeavor in Russia, in which several gold-mining companies would be consolidated, with the backing of state-owned Sberbank

- a gold-mining investment opportunity with a Russian businessman operating in Guinea

- participation in some type of transaction with Alrosa, the Russian state-owned diamond-mining company

- an allegation (by a former business partner) that Banks attempted to raise money for his stricken diamond-mining business in Russia, with apparent further assistance promised from Alrosa

There is no evidence that Banks ever acted on these offers. For two years, however, Banks insisted he only met the Russian ambassador once before the referendum, even detailing the event in his book about the campaign, The Bad Boys of Brexit.32Carole Cadwalladr and Peter Jukes, “Arron Banks ‘Met Russian Officials Multiple Times Before Brexit Vote,’” Guardian, June 9, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/jun/09/arron-banks-russia-brexit-meeting. But, this was a misleading statement: it has since become clear that there were multiple meetings to discuss a variety of business opportunities. Why Russian diplomats and intelligence officers would repeatedly dangle such opportunities in front of a British businessman whose companies were highly indebted has never been explained.

When emails surfaced suggesting there had, in fact, been three meetings, Banks admitted to these three meetings only, then revised this to four in a subsequent interview with the New York Times.33David D. Kirkpatrick and Matthew Rosenberg, “Russians Offered Business Deals to Brexit’s Biggest Backer,” New York Times, June 29, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/29/world/europe/russia-britain-brexit-arron-banks.html. A former business partner in South Africa has now alleged in an affidavit uncovered by Channel 4 News that as Banks’ diamond mining business in South Africa fell into difficulties, Banks told his worried partners he was visiting Russia to try and raise money. “Arron Banks was in discussion with Alrosa, the Russian state diamond producer, and he had made certain promises to them,” the affidavit reads. It continues:

“The most important was that Arron Banks was to prove to Alrosa the quality of diamonds produced…He was further due to meet representatives, in London, in November, where he would be obliged to show them the quality of the production.”“34Long Read: The Arron Banks Allegations,” Channel 4, July 27, 2018, https://www.channel4.com/news/long-read-the-arron-banks-allegations.

Separate emails now reported in the New York Times and elsewhere confirm that an Alrosa opportunity was, indeed, offered to Banks by the Russian ambassador in London.35Kirkpatrick and Rosenberg, “Russians Offered Business Deals to Brexit’s Biggest Backer.” One of the Russian intelligence officers with whom Banks was in touch, Alexander Udod, was subsequently expelled, following the Sergei Skripal attack.36Lucy Fisher, “Brexit Millionaire Arron Banks Briefed CIA on His Russia Talks,” Times, June 11, 2018, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/brexit-millionaire-briefed-cia-on-his-russia-talks-8rg6l93vj. The Observer has since alleged that Banks actually met with Russian officials eleven times, and that the ambassador kept in touch with him by text message. Two of these rendezvous took place in the same week that Leave.EU was officially launched to the public.37Carole Cadwalladr and Peter Jukes, “Revealed: Leave.EU Campaign Met Russian Officials as Many as 11 Times,” Guardian, July 8, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jul/08/revealed-leaveeu-campaign-met-russian-officials-as-many-as-11-times.

There are further worrying connections. When asked whether he had ever sent documents to the Russian embassy regarding the FBI’s arrest of George Cottrell, a Nigel Farage aide, on money-laundering charges, Wigmore—Banks’ right-hand man—denied before a parliamentary committee that he had ever done so.38Carole Cadwalladr and Peter Jukes, “Leave. EU Faces New Questions over Contacts with Russia,” Guardian, June 16, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jun/16/leave-eu-russia-arron-banks-andy-wigmore.

After the hearing, the Observer published another email contradicting Wigmore’s account. He had actually sent legal documents about Cottrell’s arrest to a Russian officer stationed at the London embassy. The email stated simply, “Have fun with this,” and contained several attachments, the contents of which are not yet known.39Ibid. There has never been any public reporting that the arrest of the Farage aide had anything to do with Russia, begging the question of why Wigmore sent these documents to the Russian embassy at all.

Banks, then, is a businessman who appears to be consistently in some degree of financial trouble. His extraordinary generosity is not matched by a clear-cut explanation of how he can afford the donations; openDemocracy estimates that the major contribution to his personal net worth—the sale of Brightside—came to just over £22 million, and that most of his other endeavors have been requiring, rather than generating, cash. Banks has changed his story about interacting with Russian officials several times; each new admission includes more meetings and increasingly complex deals.

Where the money came from remains the key question. Present electoral rules do not require Banks to explain. Even his closest associate, Wigmore, has been unclear about the source of funds, and his explanation is contradicted by the facts. Banks’ other former business associate, Jim Pryor, told the BBC in July 2018:

Journalist: Are you worried about where that money might have come from?

Pryor: Worried? It is a lot of money, you know, and it’s sure to raise a lot of questions. Yes, I would like to know. Maybe I’ll sit down with Arron and ask him one day.

Case study 3: small donations

US campaign-finance rules governing small donations allow for anonymity on the basis of several principles that were reasonable in the pre-digital era. The underlying assumption is that personal political affiliation is a private matter that should not be open to disclosure; just as the voting booth is private, so are small donations. Since the sums involved are modest, there can be no reasonable expectation of special favors in return. In addition, registering the origins of donations of $50 or $100 would impose a needless bureaucratic burden.

The advent of electronic money, cryptocurrency, and crowdfunding changes all of this, and makes the distinction between small and large donations effectively meaningless.

Crowdfunding is the digital equivalent of bucket collecting. In general, donations can be collected through a third-party platform, or directly by the entity itself through its own website. Crowdfunding has been applied to business, creative, and charity projects, as well as political activism and campaign projects—however, it increasingly helps raise funds for regulated political organizations and candidates.

Platforms now exist—notably CrowdPac and Flippable—to perform this function in the United States.40Kate Conger, “Crowdfunding Platforms Take a Data-Driven Approach to State Political Campaigns,” TechCrunch, April 14, 2017, https://techcrunch.com/2017/04/14/a-data-driven-approach-to-state-political-campaigns/?guccounter=1. Both platforms are aligned with the Democrats, who pioneered this form of political fundraising. CrowdPac fired its co-founder, Steve Hilton, after he took a job as a Fox News pundit, and it no longer allows Republicans to fundraise using the platform. Meanwhile, Flippable only targets seats that can flip from Republican to Democrat.

No equivalent platforms exist on the Republican side, but candidates for any US party can, and do, raise small donations on their own websites, which allow supportive visitors to donate using their credit or debit cards. The identity of these small donors is presently protected under three layers. The first layer is electoral law, which does not require donors to identify themselves, unless they contribute more than $200 (in the UK, this limit is £500). The second is consumer-privacy legislation, which places the burden of responsibility on the receiver of funds not to reveal sensitive data about those sending in money, in the same way that online retailers are typically bound to safeguard their customers’ delivery addresses and other personal data. The third layer of protection is the contractual relationship between the recipient organization and whichever third-party providers actually process these card transactions. In some cases, receiving parties choose to rely on a third-party card-payment-processing company to avoid the responsibility of protecting too much personal data at any one time.

Third-party providers of payment-processing services for political organizations are not allowed to publicize or privately share payment details (for example, names and addresses linked to credit cards) with journalists or other investigators.

This triple-lock protects legitimate small-value donors, but could also provide cover for the impermissible support of candidates by foreign actors, using anonymized cashless-payment cards, cryptocurrency, and various other subterfuges. This process could even be automated in a number of ways. This would be hypothetically attractive to candidates because, even if the abuse is exposed, the candidate can credibly claim to have no knowledge of these donations.

By the time of the 2016 US presidential election, the increase in the value of small donations was noticeable. Donald Trump and his two joint-fundraising committees, Trump Victory and Trump Make America Great Again, ended up raising a total of $624.4 million.41Note that Trump received $462.8 million of this total, with other recipients including the Republican National Committee, as well as local branches of the party. Fifty-nine percent of those total receipts came from donations below the $200 reporting threshold.42Campaign Finance Institute, press release, “Analysis of the Final 2016 Presidential Campaign Finance Reports,” February 21, 2017, http://www.cfinst.org/press/preleases/17-02-21/President_Trump_with_RNC_Help_Raised_More_Small_Donor_Money_than_President_Obama_As_Much_As_Clinton_and_Sanders_Combined.aspx.Center for Responsive Politics, “Summary Data for Donald Trump, 2016 cycle,” OpenSecrets.org, https://www.opensecrets.org/pres16/candidate?id=N00023864. Center for Responsive Politics, “Trump Victory: Joint Fundraising Committee,” OpenSecrets.org, https://www.opensecrets.org/jfc/summary.php?id=C00618371&cycle=2016. By comparison, the average raised by campaigns over 2016 from small (under $200) donations, stood at only 32 percent.43Center for Responsive Politics, “Those Prized Small Donors? They May Not Be as Small as You Think,” OpenSecrets.org, https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2017/04/small-donors-may-not-be-smol-as-you-think/.

Not only did Trump raise $20 million more from small-value donors than Barack Obama did in 2012, but he also managed to bring in $2 million more than candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders combined in 2016. He did this over a very short time frame: just four months.44Sophie Kaplan, “Trump Raised More Dollars from Small Donations,” PolitiFact, November 13, 2017, https://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2017/nov/13/kayleigh-mcenany/trump-raised-more-dollars-small-donations/.

It should be noted that an individual is permitted to make multiple donations under the $200 limit, although it can be argued that this is not in the spirit of the law.

Trump’s campaign team has presented these statistics as a positive, positioning him as a candidate with genuine support from grassroots donors.45Ibid. But, because it is without a doubt technically possible to automate and anonymize these donations electronically, the money actually came from unknown sources.

The use of cryptocurrencies makes the problem thornier still. A group of Trump supporters launched TrumpCoin in February 2016, saying it was launching “a digital currency outside this system, free from the inadequacies of the globalist establishment.”46“Introducing: TrumpCoin,” TrumpCoin Content, May 25, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMM-X0mDonI&feature=youtu.be. The group initially put aside two hundred thousand coins, which members said they would donate to the Trump campaign, and encouraged investors to put any profits from their own purchase of coins into the campaign, too.47BitCoin Forum, February 17, 2016, https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=1367265.0. The project’s market capitalization peaked in January 2017, with a market capitalization of $5.5 million, and spiked again in January 2018.48Jonathan Deller, “TrumpCoin Surges 227% as President Boasts of Being ‘a Very Stable Genius,’” Altcoin Sheet, January 2018, http://www.altcoinsheet.com/2018/01/trumpcoin-surges-227-as-president.html.

Small_Donor_Money_than_President_Obama_As_Much_As_Clinton_and_Sanders_Combined.aspx.

It is unclear how much of this money ever made it into the Trump campaign. Because the only way to purchase TrumpCoin was with Bitcoin, however, it would have been relatively straightforward for a malicious actor to have channeled money from impermissible sources into the Trump campaign, with or without the candidate’s consent.49Daniel Roberts, “Bananacoin? Trumpcoin? The 7 Strangest Cryptocurrencies,” Yahoo! Finance, February 8, 2018, https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/bananacoin-trumpcoin-7-strangest-cryptocurrencies-112657021.html?guccounter=1. Furthermore, TrumpCoin was available for purchase on six cryptocurrency exchanges, all of which were based overseas; one, YoBit, was in Russia.50Deller, “TrumpCoin Surges 227% as President Boasts of Being ‘a Very Stable Genius.’” Although Trump never endorsed the coin directly, on April 1, 2016, he said at a rally in Wisconsin:

“Listen up folks, we gotta be smart about campaign donations. Look at Ted Cruz. He’s being bankrolled by the big banks…We gotta start making campaign donations cryptocurrency-only. That’s right. We need to get the big banks out of it completely.”51Joël Valenzuela, “Trump Calls to Make All Campaign Donations Crypto, Launches TrumpCoin,” Cointelegraph, April 1, 2016, https://cointelegraph.com/news/trump-calls-to-make-all-campaign-donations-crypto-launches-trumpcoin.

There is no suggestion that TrumpCoin was ever exploited by a malicious foreign actor, but its role, while entirely legal, was highly vulnerable to foreign manipulation.

Alternative currencies are making some headway more broadly in the US donations ecosystem. Republican Andrew Hemingway first used them in his 2012 bid to become governor of New Hampshire. Although he lost the race, about 20 percent of his donations came from Bitcoin.52Ibid. It took until May 2014 for the Federal Election Commission to formally approve cryptocurrency donations.53Jason Koebler, “Why Bitcoin Could Actually Be Bad for Rand Paul’s Campaign,” Motherboard, April 7, 2015, https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/539eza/why-bitcoin-could-actually-be-bad-for-rand-pauls-campaign. A slew of Democrats and Republicans have since experimented with accepting cryptocurrencies, often using third-party provider BitPay to handle payments.54Jordan Pearson, “How to Trace a Political Donation Made with Bitcoin,” Motherboard, April 8, 2015, https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/pgawp8/how-to-trace-a-political-donation-made-with-bitcoin. Senator Rand Paul began accepting Bitcoin donations for his presidential bid in 2015.55Matea Gold, “Federal Election Commission Approves Bitcoin Donations to Political Committees,” Washington Post, May 8, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2014/05/08/federal-election-commission-approves-bitcoin-donations-to-political-committees/?utm_term=.340debc1b3d6. Kansas has since taken a different view, banning cryptocurrency donations altogether. A spokesperson said they were “too secretive” and “worse than the Russians.”56Valenzuela, “Trump Calls to Make All Campaign Donations Crypto, Launches TrumpCoin.”

There are ways to trace the identity of cryptocurrencies’ owners through blockchain analysis, but they are not straightforward. By taking additional measures, adept cryptocurrency users can make it nearly impossible for investigators to discover their real identities. Note that Senator Paul, like other candidates, asked for donors to identify themselves when they made donations using Bitcoin—but there was no mechanism to ensure they did so truthfully.57Pearson, “How to Trace a Political Donation Made with Bitcoin.”

Conclusion

The good news is that excluding foreign dark money is relatively straightforward compared to combating disinformation, for example: it is an entirely viable project, if the political will exists. At present, however, two of the key affected groups are hamstrung by conflicting interests. Political parties are widely reluctant to pass laws that constrain their ability to raise money. Meanwhile, intelligence and law enforcement organizations are reluctant to engage in domestic political matters for fear of being themselves accused of meddling, and becoming embroiled in political struggles.

Politicians throughout the democratic world now need to grasp the seriousness of the threat and voluntarily accept some restraints on their own fundraising operations. They also need to provide a clear mandate to government institutions to enforce these rules.

This report is not an argument for state funding of political parties: independent financing of political activity is essential to a vigorous democracy. But this funding must be properly regulated and must not be an invitation to foreign subversion.

Similarly, the temptation to enact draconian regulations covering political funding should be resisted; they would be burdensome and counterproductive. More important, if the openness of the political system is substantially reduced, it would be a victory for adversaries.

Bearing in mind these constraints, and drawing on events that occurred in liberal democracies during 2015-2018, we propose a series of measures that should disrupt and deter those who would launder money from hostile states using democratic politics. This is already established by law as illegal, but legislation and enforcement have become hopelessly obsolete in this area.

In many democracies, electoral legislation is obsolete, weak, and full of loopholes. It takes little or no account of parallel organizations, cryptocurrency, or the likelihood of well-resourced, state-level actors trying to game the system. In short, it is pre-digital, and does not anticipate the scale of foreign subversion now taking place.

A negative example is the UK’s Political Parties, Elections, and Referendums Act of 2000 (PPERA), which allows any active company established in the EU to donate to political parties regardless of ownership. The act defines these corporate donors as follows:

A company—

(i)[registered under the Companies Act 2006], and

(ii)incorporated within the United Kingdom or another member State,

which carries on business in the United Kingdom.58UK Parliament, Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000, Section 54 (London: Queen’s Printer of Acts of Parliament, 2000), https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/41/section/54.

These apparently innocuous lines are highly significant. For example, an oil-trading company registered in London and 100-percent owned by CNOOC or Gazprom would be a permissible donor, as long as it could be shown to be actively trading. The only reason that adversaries take the trouble to launder money in the British system is to obscure their intent; if they chose to, they could donate quite legally. The government of Prime Minister David Cameron promised to close this loophole, but failed to do so.

In the UK, both Northern Ireland (thanks to its obsolete donor-anonymity rules, dating from the time of the Troubles) and Scotland (owing to its opaque Scottish LLP structures) offer loopholes that have been exploited.59James Cusick, “‘Substantial’ Fine Linked to DUP’s Secret Brexit Donors,” openDemocracy UK, October 17, 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/uk/brexitinc/james-cusick/substantial-fine-linked-to-dup-s-secret-brexit-donors.David Leask, “Scottish Shell Firms Used to Launder Tens of Millions of Dollars Looted from Ukraine by Country’s Former Leaders Revealed,” Herald, January 7, 2018, http://www.heraldscotland.com/news/15812266.Video__Edinburgh_and_the_oligarchs/. In the United States, tax havens such as Delaware, Wyoming, and Nevada—in combination with the use of PACs and foundations—are similarly inviting.

Across the board, clubs, companies, and councils provide an equally open invitation to dark money (as seen in the AfD case study and the use of super PACs).All three of these types of organizations are being used to hide donors’ true identities. Equally important, auctions and fundraising events often provide unregulated spaces, as has been documented in the cases of British Conservative events that were strongly supported by Russian donors.

In terms of enforcement, organizations like the US Federal Election Commission and the UK Electoral Commission are notoriously toothless. In the UK, when intelligence or law-enforcement support is required, there is no organization like the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) that combines counterintelligence with forensic investigation and bringing cases to court. The same is true in Germany, where the relevant bodies are also fragmented between the federal states.

In early 2018, Australiapassed several pieces of legislation designed to address foreign subversion, with a third still under review.60Evelyn Duoek, “What’s in Australia’s New Laws on Foreign Interference in Domestic Politics,” Lawfare, July 11, 2018, https://www.lawfareblog.com/whats-australias-new-laws-foreign-interference-domestic-politics This was in part prompted by a media investigation showing that $6.7 million had been donated to two political parties by a pair of Chinese businessmen in 2015-2016. Warnings to all parties by the Australian security service were ignored. One of the same donors was instrumental in the scandal surrounding Labor Senator Sam Dastyari, who received benefits from the businessman and then took China’s side in the South China Sea dispute.

Of course, this makes investigations extremely difficult, but it also points toward an obvious conclusion: offshore jurisdictions facilitate not only criminal activity, tax evasion, and terrorist financing, but also hostile intelligence activity.61Neil Barnett, “Dirty Foreign Money’s Existential Threat to Democracy,” American Interest, March 22, 2017, https://www.the-american-interest.com/2017/03/22/foreign-moneys-existential-threat-to-democracy/. Law enforcement organizations will never uncover these operations in full, but the major global economies can and should take action to stop them at their root, by shutting down tax havens. Ultimately, the aim is to establish a workable regime of transparency in which permissible donors face no serious obstacles, whereas impermissible donors face insurmountable deterrents.

Politicians and political organizations need to accept the threat of political money laundering and yield political ground to combat this problem. Political parties genuinely committed to preventing foreign interference in democratic systems should first view themselvesin the context of the national interest. They should ask hard questions of their own policies, funders, and associated organizations, acknowledging that they will have to surrender some latitude in fundraising if democratic integrity is to be maintained. These commitments should be explicitly spelled out to those committees and officials charged with reforming regulation and with enforcement. If political parties insist on preserving their traditional flexibility in fundraising, reform will be stymied from the outset.

Political money laundering and efforts to subvert elections need to be seen as national security issues. Security policy should include new provisions to protect democracy itself; these provisions should be viewed as a form of hard security. Authoritarian states have clearly made attacking democracy a central element of their security policies, so liberal democracies should counter the threat with their own defensive doctrines. The guiding principle should be shutting down access by hostile states while maintaining openness; if openness is compromised, adversaries win. The UK Strategic Defense Review and US Quadrennial Defense Review, for example, provide a good context for setting out policy and integrating it with other forms of security policy.

Secrecy jurisdictions must be recognized as a national security threat. Offshore tax havens, which establish opaque company and trust structures, are national security threats, allow for tax evasion, and facilitate criminal money laundering. Like loopholes in campaign finance legislation, tax havens have mutated into a more serious threat and should be treated as such. Their restriction and ultimately elimination is well within the reach of the G7 group if the will exists.

The UK has taken the lead62Madison Marriage and Henry Mance, “Why British overseas territories fear transparency push,” Financial Times, May 2, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/1247850c-4e14-11e8-a7a9-37318e776bab by insisting that several offshore territories (including the British Virgin Islands and the Caymans) implement transparency measures by 2020. The threat posed by onshore money in London is also being addressed.63Caroline Wheeler and Tom Harper, “Dirty Russian money threatens Britain, says MP,” Times, May 20, 2018, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/oligarchs-influence-and-dirty-money-threaten-uk-7f2mzd2dk. As with earlier initiatives, however, there is a danger that undertakings and recommendations will not be fully enacted or enforced.64Prem Sikka, “Tax-haven transparency won’t stop money laundering in Britain,” Guardian, May 8, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/08/tax-haven-transparency-money-laundering-britain. Equally, the US has onshore secrecy jurisdictions like Delaware and Wyoming. These are particularly attractive for subversion purposes, as they suggest domestic origins.

In order ensure the integrity of the right to representation, citizens must contribute toward society and fulfil their tax obligations. The tax system provides a ready-made verification mechanism. A rule stating that “funds raised for political parties or support thereof must come from taxed businesses, individuals or entities” ought to be uncontroversial. It could rest on the same principle as suffrage: “No taxation without representation,” or, rather, “No representation without taxation.” Why should money kept in Caribbean tax havens be allowed to influence politics? The obstacle to this rule in the United States would be the preponderance of funds donated through tax-efficient charitable structures (e.g., nonprofits). Nonetheless, this could be managed, again by placing the burden of proof on the donor. Opponents of such a measure would find it difficult to argue against this when most voters pay taxes themselves.

In the small-donations case study, this report argues that anonymity for small donations under $200 is obsolete. Here, one approach could be to require regulated political organizations to adopt practices similar to the financial-services industry and ask for mandatory reporting of suspicious activity to the election regulator. If a single actor posing as hundreds, thousands, or millions of individuals is illegally funding a political party, there would necessarily have been a degree of automation, which would create repetitive patterns or other anomalies in payment data. Recipient organizations would also need to agree to random audits of their payment data, to check that irregular patterns of fundraising from donors under the usual reporting threshold are not being ignored.

Second, there must be better efforts to verify whether an online donor is who they say they are. Verifying one’s identity is part of the established process of engaging with any government body or utility provider, and there is no reason that citizens should not be expected to do the same when engaging in the important democratic processes that define societies. The UK government already works with seven companies, including Experian, Digidentity, and Barclays, to fully verify donors’ identities; the process takes between five and fifteen minutes, with all checks conducted using online tools.65UK Government, “Guidance: GOV.UK Verify,” last updated September 3, 2018, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introducing-govuk-verify/introducing-govuk-verify. According to the same logic, anonymous payment methods—principally, cryptocurrency and cashless payment cards—should be excluded from political donations altogether.

In addition, political consultancies (such as strategy advisers and digital-services providers) should be required to register in the same jurisdiction as the entity for which they work, so that swift access by electoral-commission investigators can be arranged if needed. Note that the government of Lithuania has been trying to institute this rule but has run afoul of EU single-market rules, as would other states trying to do the same. This, then, becomes a problem that needs to be solved at the Brussels level.

In most Western countries, cooperation between intelligence and law enforcement agencies needs significant strengthening. This is particularly true in the UK, where an unpoliced area exists on the border between counterintelligence and law enforcement. The police and the National Crime Agency (NCA) can build criminal cases for prosecution, but they have no discrete counterintelligence role. The Security Service (MI5) holds this role, but lacks forensic capacity. It also lacks the international reach of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). The result is a large degree of confusion and uncertainty over which organization, if any, has a mandate to act.

In Germany, the situation is arguably worse, owing to a proliferation of agencies that are hamstrung by conflicting political messages, regional fragmentation, and a reluctance to employ counterintelligence at all. The Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, BfV) should take the lead on countering subversion, but is reliant on the regional cooperation of Landesbehörden für Verfassungsschutz (State Offices for the Protection of the Constitution, LfV). These organizations cannot bring prosecutions, and, therefore, would need to cooperate with the Bundeskriminalamt (Federal Criminal Police Office, BKA). It is not helpful that the federal government is in Berlin and the BfV is headquartered in Cologne, with the BKA in Wiesbaden and the LfVs scattered throughout Germany.

By comparison, the US system, in which the FBI combines counterintelligence and criminal investigations, is far more suited to the challenge. Moreover, the FBI has become adept at cooperating with the CIA and other agencies since 9/11. While not perfect, it is nonetheless a model from which the UK, Germany, and other allies could learn.

Anti-money laundering (AML) legislation may be the simplest, and most effective, way to address the operations described in this report. Once hostile operations are identified by intelligence or law-enforcement organizations, AML investigations can be used to take them down, thus avoiding the political and legal difficulties of bringing espionage or treason cases. Again, connected and properly resourced security and financial-crime organizations are urgently needed, particularly in Germany and the UK. Equally, a specific, senior law-enforcement official should be made responsible for countering foreign political-subversion activity. This strand would be greatly facilitated by action against tax havens, as noted in the previous point.

Recently introduced “Unexplained Wealth Orders” in the UK are another useful piece of legislation, forming a broader AML framework; they should be used judiciously as a deterrent.

In the case of media support for AfD, at least €20 million of unknown origin was used to buy direct media support for the party. The denial by party officials of any connection between it and the Rights and Freedom Club meant that the spending was not covered by electoral-spending regulation. In the United States, super PACs often perform a similar role. Electoral law should be reformed to ensure that direct support—such as the buying of advertisements for a candidate or party—counts as regulated spending. Political “movements” that act as de facto parties should be treated by law as parties, so that they cannot be used to circumvent regulations. This would require tracking variables such as the extent of funding, nature of activities, and connection to electoral candidates.

In democracies, intelligence services are naturally unwilling to involve themselves in matters of domestic politics—which is a good thing in most cases. Nonetheless, their involvement is needed in cases of political money laundering, and should be formalized in a way that gives the agencies the mandate and confidence they need when a credible threat is detected. Where there are reasonable grounds to suspect that funds come from a hostile power, a judge could mandate that security services, police, and prosecutors mount an investigation.

Politicians and major funders alike should be required to make full wealth declarations, including disclosure of their tax returns and assets held in all jurisdictions. Romania already applies this rule to parliamentarians, in order to deter political corruption, and has seen some success.66Dmytro Kotlyar, Asset Disclosure and Wealth Assessment System in Romania: Lessons for Ukraine (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017), http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/249791468186256465/pdf/102311-WP-ENGLISH-Asset-disclosure-and-wealth-assessment-system-in-Romania-Case-study-Box-394830B-PUBLIC.pdf.

The Ultimate Beneficial Owner (UBO) of donated funds should be declared and verified. Most importantly, the burden of proof must fall on the donor. If he or she cannot satisfactorily demonstrate the origin of the funds, those funds should be excluded. In this way, effective deterrence is implemented without intrusive and burdensome regulations.

As well as bolstering defensive measures, democracies should consider offensive economic measures, particularly targeting individuals and companies proven to have participated in subversive activities. This would deter Russian and Chinese oligarchs and major companies. The model here would be the US Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), which is essentially a tool of economic warfare.67US Department of Treasury, “Terrorism and Financial Intelligence,” https://www.treasury.gov/about/organizational-structure/offices/Pages/Office-of-Foreign-Assets-Control.aspx.

The law should provide for specific deterrents under espionage and treason legislation, including substantial jail terms. New Australian legislation sets out terms of fifteen to twenty years “for a person to knowingly engage in covert conduct or deception on behalf of a ‘foreign principal’ or ‘to attempt to influence a target in relation to any political process or exercise of an Australian democratic right on behalf of or in collaboration with a foreign principal if this foreign connection is not disclosed to the target.’”68Douek, “What’s in Australia’s New Laws on Foreign Interference in Domestic Politics.” For what is essentially treason, and a crime that can have catastrophic consequences for the target state, this seems proportionate.

Policy recommendations

At the outset, it is important to note that the measures outlined below are intended as general principles. They are not tailored to any specific state, but are meant be used as guidelines for reform generally.

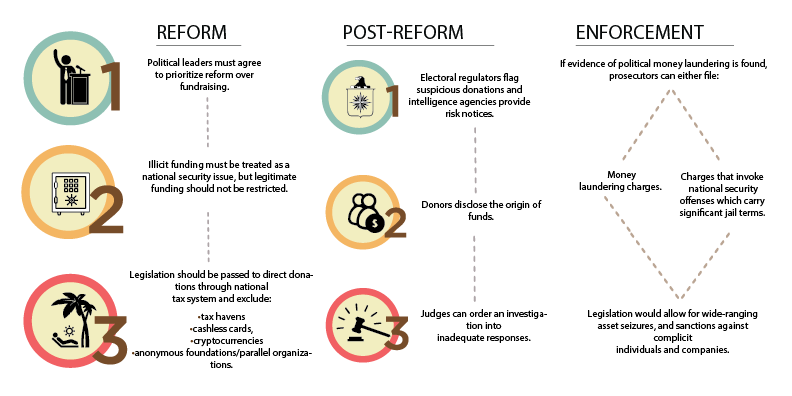

These policy recommendations together form a layered defense against political money laundering (See Figure 1). For them to succeed, however, several steps are necessary. First, political leaders must agree that reform is needed, and accept that they will need to give up some of their leeway in fundraising. Reform must then be handled as a national security issue, focusing on illicit funding while maintaining openness to legitimate funding. Legislation should then be passed to ensure that donated funds pass through the national tax system, and to exclude funds from tax havens, cashless cards, cryptocurrencies, and anonymous foundations and parallel organizations.

Post-reform, electoral regulators would flag any donations they consider suspicious; intelligence agencies would also be able to provide the regulator with risk notices. In the first instance, the regulator would invite the donor to disclose the origin of funds, with the burden of proof falling on the donor. If the donor’s response is inadequate, a judge would be able to mandate an investigation; ideally, the investigating body would combine criminal investigation with counterintelligence functions.

Figure 1. A proposed layered defense system against political money laundering

Should infringements be discovered, prosecutors would have the choice of pursuing a traditional money-laundering case or invoking specific national security offenses that carry significant jail terms. Legislation would also allow for wide-ranging asset seizures, and sanctions against complicit individuals and companies.

Key policy recommendations include:

- Accept the gravity of the threat of political money laundering and be prepared to yield political advantages to address the issue.

- Treat political money laundering and electoral subversion as national security issues

- No representation without taxation

- Secrecy jurisdictions are now a national security threat

- Small donations should be audited to detect irregular or unusual donation patterns and identify those donors – Crytpocurrencies and cashless payment cards must be prohibited instruments for political donations.

- Increase and improve interagency cooperation

- Draft and implement anti-money laundering legislation to prosecute political money launderers, avoiding the complexities of prosecution under national security legislation.

- Require outside political fundraising and lobbying groups to formalize relations with political parties.

- Bar foreign agents, formalize the role of intelligence services, and require politicians and major political donors to make wealth declarations and publish tax returns.

- Create punitive consequences for political money laundering that include sanctions, wide-ranging asset seizures, and substantial jail terms.