How will the rise of China’s currency impact global markets, foreign policy, and transatlantic financial regulation?

The report, titled “How China’s Currency Impacts Global Markets, Foreign Policy, and Transatlantic Financial Regulation” offers and elaborates on five principles for an effective internationalization process of the RMB:

- Agenda setting should be pragmatic, not aspirational;

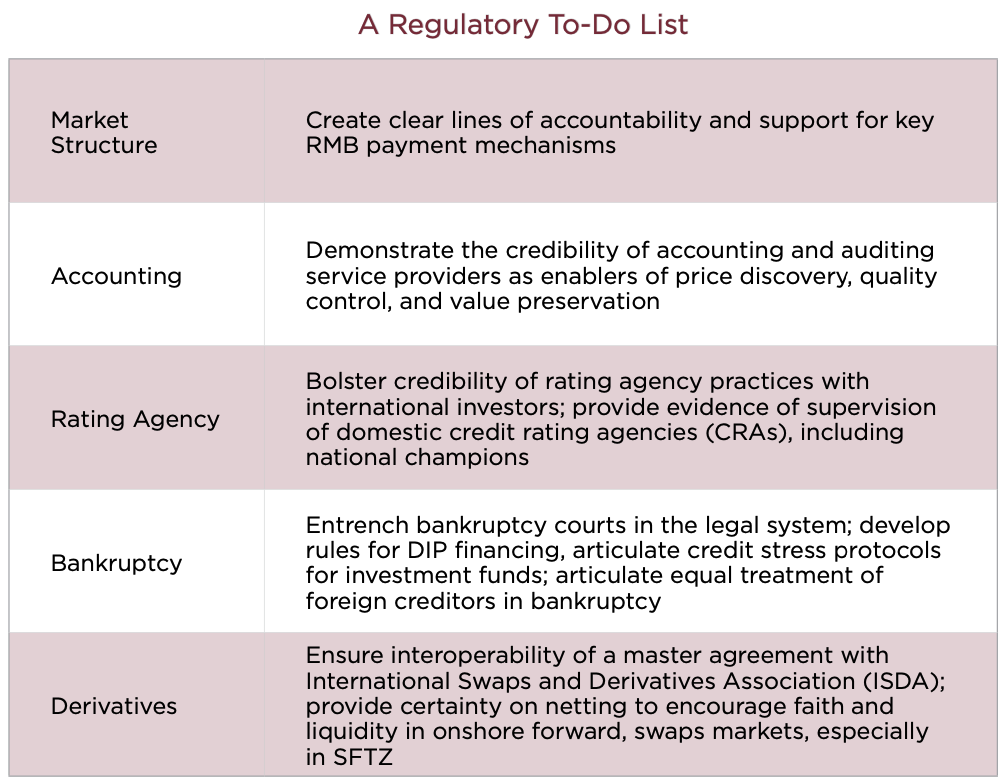

- Reforms in legal infrastructure must accompany market liberalization to meet growing RMB demand and usage, including transparency in market structure, better accounting and auditing supervision, credible ratings processes, and crisis management;

- Transpacific capacity building is required;

- Prudential concerns, nondiscrimination principles should trump politics;

- The International Monetary Fund should include the RMB in its basket of currencies – and incorporate regulatory reform in its weighting metrics.

The suggestions highlighted above articulate a measured approach for constructively engaging the rising prominence and popularity of the RMB that integrates developments in capital and currency account liberalization, financial regulation, and economic growth for both China and globally.

Governor Jon M. Huntsman, Jr., Chairman of the Atlantic Council, serves as the report’s chair, and Atlantic Council C. Boyden Gray Fellow on Global Finance and Growth Dr. Chris Brummer served as rapporteur.

Table of contents

The currency internalization process–and what makes China different

The launch of RMB internalization: offshore deposits and trade settlement

Onshore investment channels: QFII, RQFII, and the Interbank Investment Program

Offshore RMB investment via the offshore RMB bond market

The global growth of RMB financial centers

How RMB bank transactions are cleared and settled

Principles for an effective internalization process

Foreword

Few issues confronting the international economy rank as high on the global agenda as the internationalization of the renminbi (RMB). As China asserts its place as the world’s biggest economy and its largest trading nation, China’s leaders and many of its trading partners are naturally supporting an increased prominence of the currency in international economic affairs. This support is paving the way for a variety of domestic reforms as well as a build-out of infrastructure internationally, all designed to elevate the currency’s status.

Nevertheless, the process of internationalization—an admittedly technical and at times political exercise—remains misunderstood and poorly explained. Policy responses in the West often fail to balance, in nonpolitical terms, the tremendous economic opportunities with the sober acknowledgment of the steps needed to ensure maximum economic prosperity and cooperation. This report, prepared by Dr. Chris Brummer, continues our highly respected Danger of Divergence series of publications examining transatlantic cooperation and takes us a crucial step closer to understanding the impact RMB internationalization will have on the global financial system. Its chapters spell out how the process is unfolding while identifying key future areas of reform and their ties to much-needed developments in global economic diplomacy. Its analysis uniquely illustrates the important link among macroeconomic, macroprudential, and macropolitical strategies.

On behalf of the Atlantic Council, the City of London Corporation, Standard Chartered, and Thomson Reuters, I hope you enjoy the report.

Jon M. Huntsman, Jr.

Chairman

Atlantic Council

Executive summary

China’s economic coming of age continues to impact the global monetary and financial systems in unprecedented ways. In the area of currency internationalization, the renminbi (RMB) attained a “G7” status in global payment currencies, and the opportunities for investing internationally and domestically have increased at an exponential pace. In just the last five years, financial authorities and diplomats have faced a series of major developments, including:

- The creation of an offshore market with few capital account restrictions;

- Targeted investment schemes into the country, with specific country and individual quotas;

- Two-way channels allowing companies to sweep money on and offshore between affiliates; and

- A series of mutual recognition programs, including the “Hong Kong-Shanghai Stock Connect” program, allowing investors to invest in one another’s on- and offshore markets.

These developments potentially carry a number of welcome advantages for the global economy and even international relations:

- Political frictions involving claims and counter-claims of “currency manipulation” could ease as RMB valuations are subject to greater market influence;

- Political frictions involving claims and counter-claims of “currency manipulation” could ease as RMB valuations are subject to greater market influence; The internationalization process can help facilitate a more competitive, consumer-oriented economy;

- Firms and investors in the United States and Europe will enjoy new means of diversifying their portfolio investments, as will China’s savers;

- Earnings made in China and other “trapped cash” will be able to be repatriated abroad, just as RMB profits earned abroad will be able to be put to use in China.

But to achieve these outcomes, stronger transatlantic and transpacific vigilance and coordination is required, along with deeper public and private sector cooperation:

- China will have to continue efforts to not only liberalize its capital account, but also to upgrade its crisis management, bankruptcy regimes, and supervision of key gatekeepers like credit rating agencies, auditors, and accountants. Capital market liberalization will have to account for frothy markets, just as will market supervision.

- The reforms already made by China and the obvious weight of the RMB achieved thus far in cross-border settlement, and increasingly investment, should be recognized by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its special drawing rights (SDR) basket of currencies. However, upcoming and future weightings of the RMB in the SDR should reflect both market and continuing regulatory reforms.

- Nondiscrimination policies and private market participation should be embraced by both China and host states of RMB capital markets in order to bolster the market liquidity and depth and to reduce financial risk and the potential for unintended frictions in foreign policy.

All in all, these requirements involve more proactive multilateral engagement with the RMB, stronger regulatory and prudential reforms, and greater private sector involvement in the securing of a robust offshore RMB capital market. With this in mind, the report below outlines the process of RMB internationalization and explains how different parts of the evolving Chinese financial infrastructure interact in a changing geostrategic context.

Key abbreviations

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

BCBS Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

CMIM Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization

IMF International Monetary Fund

ISDA International Swaps and Derivatives Association

FSB Financial Stability Board

PBOC People’s Bank of China

CFETS China Foreign Exchange Trade System

CIPS China International Payment System

CNAPS China National Advanced Payment Systems

CSRC China Securities Regulatory Commission

QFII Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor

RQFII Renminbi Foreign Institutional Investor

RTGS Real Time Gross Settlement Systems

SAFE State Administration of Foreign Exchange

SFC Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission

SFTZ Shanghai Free Trade Zone

SWIFT Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication

Introduction

Three decades of double-digit growth, fueled by strong exports and high government investment, have transformed China into the world’s leading trading nation and second largest economy—and, by some accounts, it will surpass the United States to become the world’s largest economy by as early as 2022. Indeed, even as global growth wanes, the country is still expected to average growth rates at 6.7 percent from 2015 to 2020 and 5.7 percent from 2021 to 2030.1Standard Chartered, “Global Focus: Hawks Doves and Parrots,” March 25, 2015, https://www.sc.com/en/news-and-media/news/global/2015-03-25-global-focus-hawks-doves-and-parrots.html. By that time, China will have resumed its historical place as the world’s largest economy—and its policy choices, along with those of the United States and the European Union (EU), will have the greatest impact on the scope of market opportunities available both domestically and globally.

The foundation of China’s economic strategy has until recently been its relentless peg of the country’s currency, the yuan (also called the “renminbi” or “RMB”), to the US dollar. Unlike other countries with large economies, China does not allow market forces to determine the value of its currency or the rate at which it should be exchanged with others. Instead, the RMB has been permitted to fluctuate only against a narrow band pertaining to a pre-established value. In this way, China has been able to both keep its exports competitive and achieve monetary objectives. These objectives are not unlike those sought by some developed countries, which have been seeking to jump start their economy since the Great Recession.2Recent monetary policies by Mario Draghi, for example, have been designed to weaken the euro in order to boost the flagging competitiveness of weak eurozone countries. See “Draghi’s Dangerous Bet: The Perils of a Weaker Euro,” Spiegel, January 28, 2015. Similarly, after its earlier efforts to cut interest rates hadn’t done enough to dampen interest in the franc during the initial years of the eurozone crisis, the Swiss Central bank had announced allow the franc to appreciate such that one franc bought fewer than 1.2 euros (which in 2015) it had to reverse course on. See Neil Irwin, “Skyrocketing of the Franc in One Day Holds Lesson,” International New York Times, January 17, 2015. Even the United States, according to Alan Greenspan, adopted a tacit “weak dollar” policy to help shore up the global financial system. See Alan Beattie, “Greenspan Criticises China but Warns US over Weaker Dollar,” Financial Times, November 11, 2010. The article notes Greenspan’s view that the United States is pursuing a policy of weakening its currency which is driving up exchange rates in the rest of the world.

Over the last decade, however, China has begun to alter its monetary course, in part out of necessity. As China’s development continues, and as the market for its exports softens due to slower global growth, China’s economy has reached a tipping point, where it is required to transition from an investment- and export-based economy to a consumer-based economy. Not only do its domestic consumers have to increasingly pick up the slack where the global economy has tapered off in order to sustain growth, but China will also have to make sure that it begins to moderate the stockpiles of debt it holds from foreign governments—and foreign exchange risk3In 2007, just before the financial crisis, China’s current account surplus stood at nearly 10 percent of its GDP, and the country’s foreign reserves topped $1.5 trillion. Hongying Wang, “China’s Long MarchtowardEconomic Rebalancing,” Policy Brief no. 38, Center for International Governance Innovation, April 2014, p. 11, https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/cigi_pb_38.pdf. With such massive foreign exchange exposures, the 2008 crisis galvanized Chinese authorities to rethink the wisdom of relying so heavily on exports (and the accumulation of dollar denominated reserves) as a growth strategy. Today reserves amount to over $4 trillion.—that have accumulated as a result of its persistent trade surpluses.4Though the future of such surpluses remain in doubt, the IMF predicted as late as 2012 that once US growth accelerates, China’s trade surplus—which has abated somewhat since the crisis—would rise and reach 4.3 percent of its GDP by 2017 under current trends. Ibid., p. 3. Liberalizing its monetary affairs is viewed as a means of addressing both problems by increasing the wealth of Chinese consumers (via an appreciating currency), thereby supplanting the role of exports.5Allowing the RMB to trade on the open market, and on a global basis, would provide space for the currency to appreciate—and in the process increase wages that have, like exports, been artificially cheapened (suggest sharing the fact comparing the trade-weighted appreciation/depreciation rates) due to the RMB’s peg to the dollar. As the Chinese people enjoyed more wealth, their consumption patterns would change (and increase), and shift the structure of the economy. Less debt, meanwhile, would have to be loaned out to creditor countries in foreign currencies to help them purchase (often Chinese) goods. Meanwhile, internationalizing the currency could help to allocate capital in ways that better supported both a consumer-based economy and competitive exports. Because of strict capital controls, Chinese savers have been forced either to invest in banks with capped interest rates on deposits or put their money in occasionally dodgy “wealth management products” and privately placed debt instruments called trusts (and more derisively called “shadow banks”) that now sport over RMB 13 trillion in assets. Freeing the capital account would unlock competition and give them more choices as to how to deploy their capital at home and abroad. Domestic borrowers would have to improve rates of return—and increase opportunities in services sectors sidelined in export driven economies. This would in turn lead to more money flowing from underperforming fixed assets to more productive services, health and technology sectors—and in the process boost productivity and long-term growth.

Though Chinese officials have described the resulting change in policy as a rethinking of the “cross-border use of the RMB,” market participants have overwhelmingly called the process “RMB internationalization,” largely in acknowledgment of both the immediate impact of the policy change as well as its market trajectory. However one chooses to describe it, purposely increasing a currency’s international role in the way many authorities ultimately envision has never been attempted for a country the size of China.6Although the United States did take steps to internationalize the dollar between World War I and World War II, its policy approach did not evolve along the same state-sponsored pathway as the RMB. Monetary liberalization is by definition hazardous for any economy. It permits investors to move capital in and out of a country at will and removes controls over interest and exchange rates. Furthermore, where currency values have been kept low, as arguably in the case of the RMB, internationalization potentially opens the way for currency appreciation and, by extension, a decrease in the competitiveness of exports.

Indeed, for these reasons, most developing countries that have internationalized their currencies and opened their current and capital accounts have subsequently faced recession or a financial crisis. With this in mind, China has taken careful, risk-averse steps to internationalizing the currency. For the most part, the internationalization process has been one largely channeled via the liberalization of the current account. By internationalizing the RMB through trade channels, China has been able to minimize some of the disruption that could upend the safety and soundness of its domestic banking system. Meanwhile, liberalization of the capital account—which is also necessary for internationalization, since users of a currency need avenues for not only storing capital, but also for putting it to its most productive uses—has been more incremental. The ability of investors to commit capital to the purchase and issuance of securities has depended on targeted but rapidly expanding tactical programs and schemes that are based on a variety of factors, including:

- The creation of an offshore market with few capital account restrictions (called the “CNH market” and anchored in Hong Kong by the “dim sum market”);

- Targeted investment schemes into the country with specific country and individual quotas (under initiatives termed “Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII)” and “Renminbi QFII (RQFII) programs”);

- Two way channels allowing companies to sweep money on- and offshore between affiliates (including programs establishing zones of deregulated trade and finance such as the “Shanghai Free Trade Zone”); and

- A series of mutual recognition programs, including the “Hong Kong-Shanghai Stock Connect” (HK-SH Stock Connect) program, allowing investors to invest in one another’s on- and offshore markets.7Descriptions of each of these programs are provided in the balance of this report.

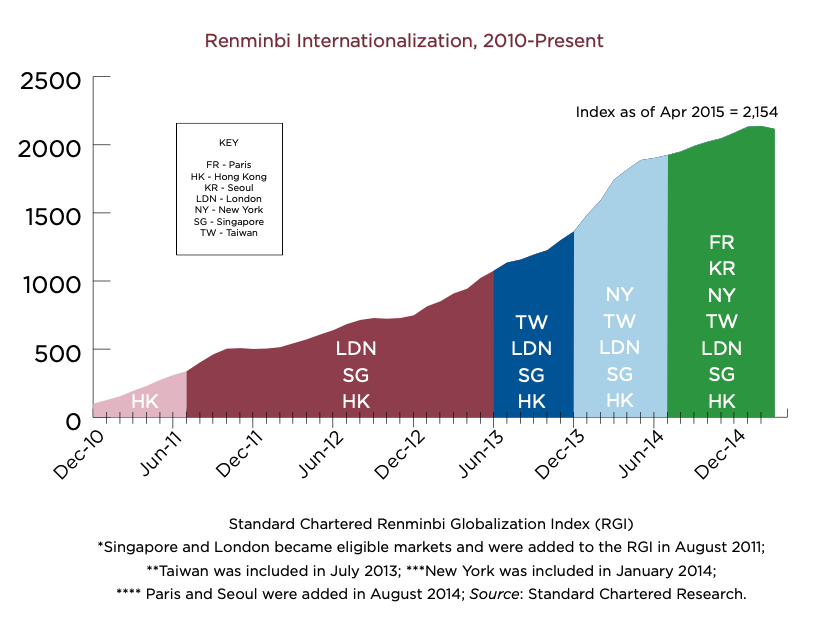

Even with its limited approach to capital account liberalization, this two-pronged strategy to currency internationalization is already transforming cross-border trade and services:

- Transactions settled in RMB have increased thirteen-fold from the first six months of 2011 to the first six months of 2012.8Sebastian Mallaby and Olin Wethington, “The Future of the Yuan: China’s Struggle to Internationalize Its Currency,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2012, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/136778/sebastian-mallaby-and-olin-wethington/the-future-of-the-yuan. The RMB is now used in more than 22 percent of China’s trade settlement;9Yves Mersch, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, speech at Renminbi Forum Luxembourg, “China: Progressing towards Financial Market Liberalisation and Currency Internationalisation,” February 26, 2014, http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2014/html/sp140226.en.html.

- RMB climbed to fifth place in the ranking of global payment currencies at the beginning of 2015, up from thirty-fifth in 2011,10J.P. Morgan Treasury Services Market Update, “China’s Economic and Political Trends and Their Impact on the U.S.,” December 10, 2012, https://www.jpmorgan.com/cm/BlobServer/China_s_Economic_and_Political_Trends.pdf?blobkey=id&blobwhere=1320602031429&blobheader=application/pdf&blobheadername1=Cache-Control&blobheadervalue1=private&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. before falling to a still impressive seventh place in the spring;

- RMB-denominated bonds have now been listed in the United Kingdom (UK), Luxembourg, Germany, and France and throughout Southeast Asia, as well as traded on the over-the-counter market. This is occurring just as firms in the United States and Europe are now directly investing in China’s onshore capital markets for the first time;11Kenneth Rapoza, “In China, European Companies Investing More Than Americans,” Forbes, May 16, 2013, 2:49 p.m., http://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2013/05/16/in-china-european-companies-investing-more-than-americans/.

- More currencies in East Asia now co-move with the RMB than with the dollar or the euro, a point most recently demonstrated by economist Arvind Subramanian. South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Singapore, and Thailand all track the RMB more closely than the dollar. The dollar only dominates in Hong Kong, Vietnam, and Mongolia. Even beyond Asia, the RMB is the dominant reference currency for Chile, India, Israel, South Africa, and Turkey.

The degree of change in some ways reflects the small base from which internationalization started, given the historically strict controls in place for the currency. But it also reflects the extent to which even modest internationalization will reshape global capital markets. Because of the closed capital account, global allocations to China (estimated at less than 0.01 percent of global portfolios) are, regardless of decelerating growth, severely underweight. This discrepancy means that even modest changes in investment behavior will have an outsized impact. China’s representation in global equity benchmarks stands at about 2 percent, even though China represents approximately 13 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and 11 percent of global market capitalization. As a result, even if (or, more accurately, when) global portfolios are reweighed in light of the unfolding regulatory changes to place China at just 5 percent, this would imply a shift of $1.5 trillion worth of assets into QFII, RQFII, and HK-SH Stock Connect or offshore bond markets, which today stand at only an estimated $77 billion in total allocated assets combined. Similarly, but over the longer term, once China’s GDP per capita reaches $40,000, which by some accounts is expected by 2050, the Investment Company Institute’s statistical analysis suggests that China’s long-term mutual fund assets could reach $11.8 trillion (or 21 percent of GDP) to upwards of $15 trillion.12L. Christopher Plantier, “Globalisation and the Global Growth of Long-Term Mutual Funds,” ICI Global Research Perspective, vol. 1, no. 1. March 2014. The question, as a result, is just how to accommodate these changes in a way that is efficient and safe for the global financial system.

A blueprint for (transatlantic and transpacific) coordination

In principle, the internationalization of the RMB, in both its current, “partially” liberalized form and in a more robust, “fully” internationalized status, holds a range of potential benefits for transatlantic investors and the global financial system:

- RMB internationalization, along with an eased capital account, portends a rebalancing of the global economy for more sustainable growth;

- Political frictions involving claims of “currency manipulation” will be eased as the RMB is subject to greater market influence;

- At its best, the internationalization process will promote market reforms in China, leading to a more competitive, consumer-oriented economy;

- Firms and investors in the United States and Europe will enjoy new means of diversifying their portfolio investments in domestic securities markets, China’s onshore markets, and other RMB financial centers;

- China’s savers, likewise, will have more opportunities to invest their savings globally; and

- Earnings made in China and other “trapped cash” will be able to be repatriated abroad, just as RMB profits earned abroad will be able to be put to use in China.

Still, internationalization creates a number of challenges from the standpoint of global governance and international economic cooperation. At a minimum, the rise of the RMB will create or exacerbate conflicts along the transmission of three very different policy dimensions:

- Monetary Policy. Even the partial internationalization of the currency will impact China’s transmission of monetary policy. Capital account liberalization will reduce the government’s ability to control interest rates and steer savings to preferred borrowers. Similarly, liberalization undermines exchange rate controls. The RMB will thus be able to appreciate, as well as potentially depreciate, depending on China’s economic fundamentals and competitiveness, as well as possible outflows of “hot money” insofar as the stock market falters and the United States raises interest rates. Still, Chinese monetary authorities, if successful in achieving moderate levels of internationalization, will begin to enjoy new powers of monetary seigniorage, just as the US dollar could see its dominance gradually erode as the global financial system develops along “multipolar” lines.

- Regulatory Policy. Internationalizing the RMB will place new pressures on the Chinese government to reform its market supervision and bolster the credibility of RMB denominated/Chinese investments and infrastructure. China’s interest rate policies will also have to continue to be liberalized in order to prevent household deposits from exiting the domestic banking system and undermining domestic financial stability. At the same time, as China’s domestic infrastructure grows and develops, and as foreign market participants operate in on- and offshore RMB markets, regulatory authorities will be increasingly well-positioned to export their own domestic policy preferences to the international community. US and EU regulatory authorities, as a result, will increasingly be not only “makers” of financial regulatory policy, but “takers” as well, creating new frictions in cross-border policymaking.

- Foreign Policy. The lucrative nature of RMB internationalization will provide the Chinese government with more tools to reward and strengthen ties with trade partners and potential allies, as well as promote the competitiveness of its onshore financial system and offshore financial institutions. US and European countries have departed on how to engage these developments. Europe has actively engaged China to construct offshore centers—and EU member states competing with one another for RMB infrastructure—while the United States has been conspicuously absent, and Toronto has aspired to become the leading RMB center in the Americas. Furthermore, over the long term, internationalization will enable the Chinese government, if it so chooses, to leverage its financial system in ways that punish actors for not only prudential, but also undesired political policy postures, in much the same way that the United States and the EU now are capable of doing. Likewise, the development of alternative channels of finance has the potential to undermine the effectiveness of US and EU use of the financial system to influence behavior.

How these fissures are handled will impact not only the speed at which the internationalization process unfolds, but also the extent to which cross-border risks and fissures are addressed and market opportunities grasped for authorities on both sides of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. In short, depending on the economic statecraft and strategy employed by policymakers, RMB internationalization can result in “currency wars” or turf battles, fragmented market structures enabling systemic risk, and diminished opportunities for firms and financial institutions to manage their foreign exchange risks.13To see how China’s influence is being transmitted through financial linkages including its controlled exchange rate movements and monetary policy, see Chang Shu, Dong He, and Xiaoqiang Cheng, “One Currency, Two Markets: The Renminbi’s Growing Influence in Asia-Pacific, China Economic Review, vol. 33, April 2015, pp. 163-178, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2015.01.013. To that end, the paper announces a range of principles—touching on legal reform, capacity building, changes in the IMF’s SDR, and, critically, nondiscrimination—and advocates a number of policy measures:

- China’s legal infrastructure should be enhanced to meet the demand and growing use of the RMB. RMB internationalization has relied on the sheer weight of the Chinese economy and expected appreciation of the currency. But as the Chinese economy slows, and the issue of internationalization reaches more skeptical policy audiences and investors, capital account liberalization will increasingly require reliable and predictable rules to support the ownership, transfer, pledging, and investment of the currency. Furthermore, Chinese authorities will have to be able to credibly demonstrate to market participants that they will have the information needed to assess the rewards, risks, and opportunities of market activities relating to the currency and RMB-denominated financial products. We thus suggest that China:

- continue to upgrade transparency concerning RMB infrastructure and RMB-denominated products, and along with current reforms in clearing and settlement, adhere to best international standards in accounting, market supervision, credit rating agencies, and derivatives contracts; and

- move swiftly to entrench bankruptcy, debtor-in-possession (DIP) financing credit stress protocols and other crisis management devices where, especially in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone, capital account liberalization is accelerating.

- Trans-Pacific capacity building is required among regulators. RMB internationalization, if successfully executed, will help establish healthier and better balanced global growth. But deeper levels of cross-border coordination will also be required.14Indeed, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee concluded in 2013 to, among other things, “speed up the building of new competitive advantage in participating in and leading international economic cooperation.” See Daniel H. Rosen, Avoiding the Blind Alley: China’s Economic Overhaul and Its Global Implications (New York: Asia Society Policy Institute and Rhodium Group, 2014), p. 55, http://asiasociety.org/files/pdf/AvoidingtheBlindAlley_FullReport.pdf. Up to this point, collaboration, even at the bilateral level, has been targeted, with select regulatory authorities (especially in Hong Kong). In the future, however, RMB internationalization will need to be subject to specifically tailored working groups at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI), International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), Financial Stability Board (FSB), and other relevant international standard setting bodies. Furthermore, even national agencies (e.g., European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), European Banking Authority (EBA), US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and others) will need to bolster staff with Chinese regulatory and market specialists or improve (and in most instances create) secondment programs with Chinese regulatory officials and vice versa in order to raise awareness and avoid needless misinterpretations and conflict as RMB denominated products and Chinese investments become more popular.

- The IMF should include the RMB as a reference currency for IMF Special Drawing Rights. The RMB is not yet included in the IMF’s basket of reference currencies. Recent reforms strongly suggest, however, that this longstanding policy stance should be reversed. The IMF itself has found the currency to be fairly valued. Moreover, China has liberalized its current account, significantly opened its onshore capital markets, and is accelerating an already unprecedented process of building offshore RMB financial centers. The IMF’s Executive Committee, led by the United States and EU, should thus devise in 2015 appropriate measures for including the RMB in the SDR. This step should, however, be operationalized thoughtfully. We propose that the RMB’s weight in the updated system should not only reflect the degree to which the currency is “freely usable” but also the extent to which sufficient macroprudential reforms have been introduced by banking and securities authorities to support capital account liberalization in a possibly volatile exchange market.

- Prudential concerns and nondiscrimination principles should trump politics—and Western institutions should participate in the internationalization process. Although currency internationalization is at times inherently a political process to the extent to which it affects levers of foreign policy, authorities supervising market participants should make regulatory decisions on economic and prudential grounds. In both jurisdictions, rules and regulations relating to the authorization of one another’s institutions to transact, trade, and operate should be clarified in advance and applied consistently regardless of national origin. Furthermore, just as the RMB should be integrated into a multilateral monetary system, Western financial institutions should be actively involved in (both market and official) clearing bank programs, data processing, and infrastructure services provision for the increasingly global RMB, both on- and offshore. In their absence, internationalization will not only be slower, but face questions of credibility in many financial centers.

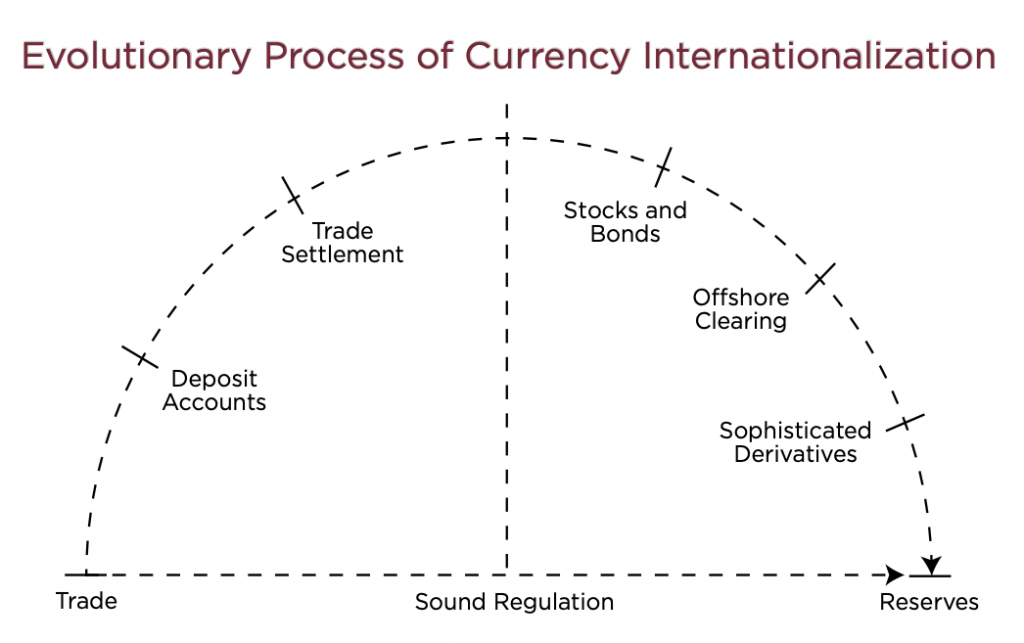

The currency internalization process–and what makes China different

The internationalization of major currencies tends to follow an evolutionary process in which a currency evolves from being merely an instrument for invoicing and trade to a means of investment and eventually a staple of central bank reserves. This continuum reflects the fact that a currency achieving internationalization has to be supported by a country with the size and weight necessary to generate and support transactions around the world denominated in its currency. It also recognizes that internationalization, though requiring a willingness of the issuing government to allow an offshore market to provide a global transmission system for the distribution and deployment of the currency, ultimately relies on the faith of market participants and foreign governments in the currency as a reliable instrument of commerce and holder of value.

This pattern identified above is one associated with the rise in dominance of the US dollar in the twentieth century. Although the dollar was adopted as the monetary unit of the United States in the late 1780s, the desirability of dollar-denominated instruments was limited due to the youth and economic fragility of the country and the absence of a national central bank. With the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913 and the post-World War I emergence of the United States as the world’s largest economy, the dollar was poised for international dominance. However, it was not until after World War II—with the launch of the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe and the creation of the Bretton Woods system (in which the US government effectively provided the world with US dollar liquidity)—that the dollar was formally recognized as the world’s international currency. And even then, global liquidity for the dollar did not fully take root until an offshore financial system based in London emerged to provide a critical distribution system for processing and recycling US dollar transactions.

China’s liberalization process hews to some of these historical patterns, while taking its own unique path. Its starting point is very different from that of the United States. In contrast to the mid-twentieth century dollar, the RMB has been largely nonconvertible and subject to capital controls and a currency peg. Its financial markets are also young and untested and have been relatively closed to the world. As a result, there is little widespread market or regulatory familiarity with the currency or with the policy of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). Indeed, Chinese authorities have not explicitly or implicitly suggested a willingness to provide the world with the RMB liquidity via official or market channels to support unfettered internationalization, or to accept the kind of volatility in its financial markets that a floating, globally-circulating and -traded currency would entail.

As a result, the internationalization of the RMB has been primarily operationalized via China’s status as a leading trading nation. Capital account liberalization has meanwhile been more incremental, with targeted channels of liberalization relating to, among other things:

- Who can move RMB on- and offshore;

- How much RMB can be moved and how often;

- Where the RMB can be moved;

- Who can invest in onshore and offshore RMB capital markets; and

- How much (and what kind of) permission is required to do any of the above.

This approach to currency internationalization has both market and strategic relevance. Partial liberalization gives policy space for regulating the flow of money in and out of the country and can meaningfully assist in curbing macroprudential risks in the absence of mature financial market supervision. It can also allow officials to ease the blow of deep structural reform. But many critics have argued that selective liberalization provides additional opportunities for discrimination against foreign enterprises and market participants, for both political and economic purposes, and can slow the implementation of changes needed to secure the long-term success of China’s economy.

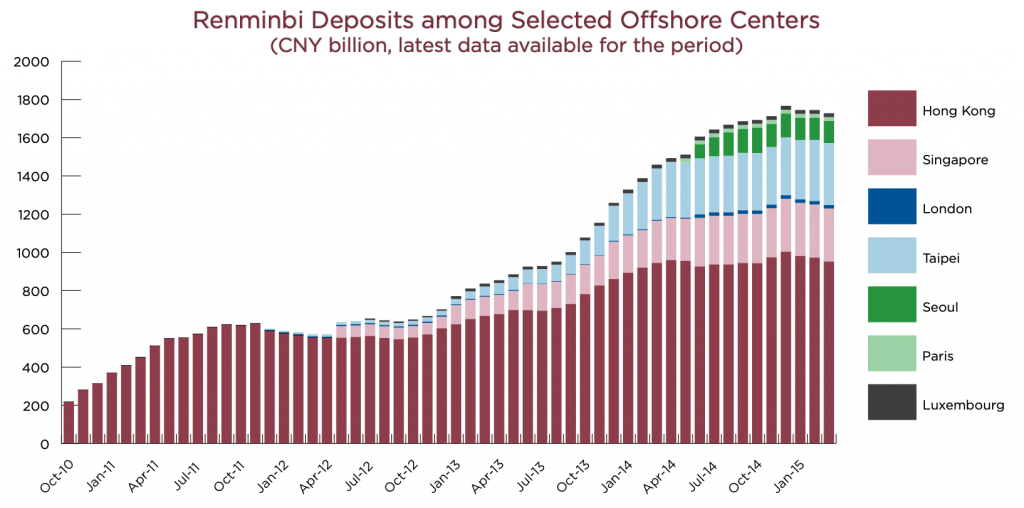

The launch of RMB internationalization: Offshore deposits and trade settlement

The internationalization of the RMB has its origins in 2004, when the Chinese government permitted the creation of offshore RMB bank accounts. For the first time, people could hold and manage RMB savings outside the mainland that are subject to local rules and protections.15There were, however, limits that until recently restricted how much individuals could buy in the foreign exchange market, and stood at 20k CNH from 2005 to 2014. See Becky Liu, “CNH CGB Auction: Yield Curve to Flatten Further,” Standard Chartered, November 12, 2014, p. 4, https://research.standardchartered.com/configuration/ROW%20Documents/CNH_CGB_auction__Yield_curve_to_flatten_further_12_11_14_10_03.pdf. Then in 2010, following a breakthrough clearing agreement signed between Hong Kong and Chinese monetary authorities, the RMB became transferable between accounts16Paola Subacchi and Helena Huang, “The Connecting Dots of China’s Renminbi Strategy: London and Hong Kong,” Chatham House, September 2012, http://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/public/Research/International%20Economics/0912bp_subacchi_huang.pdf. and virtually “all restrictions on [offshore] foreign exchange transactions, borrowing, and lending in CNH by Hong Kong and foreign institutions” were eliminated.17Joseph E. Gagnon and Kent Troutman, “Internationalization of the Renminbi: The Role of Trade Settlement,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 2014, p. 2, http://www.iie.com/publications/pb/pb14-15.pdf. From there, global deposits surged, as they could be used to hold the currency as a store of (presumably appreciating) value, fund purchases of RMB-denominated goods and services, and contain the proceeds of increasingly efficient offshore RMB fundraising.

Yet even this growth would not have been possible without China’s 2009 decision to open its current account. Up to that point, commercial (trade) transactions had to be settled in a major foreign currency, usually US dollars or, to a lesser extent, Japanese yen. But in the wake of the 2008 crisis and the subsequent heightened concerns regarding foreign exchange exposures, the PBOC—China’s central bank—initiated a pilot program whereby companies approved by mainland authorities would be permitted to use RMB to settle trade payments with customers or producers outside of China.18ASIFMA, Standard Chartered, and Thomson Reuters, RMB Roadmap (May 2014), http://www.asifma.org/uploadedfiles/resources/rmb%20roadmap.pdf. Two years later, the program was extended to exporters and importers throughout China, effectively liberalizing the country’s current account.19Barry Eichengreen, Kathleen Walsh, and Geoff Weir, Internalisation of the Renminbi: Pathways, Implications and Opportunities (Sydney: Center for International Finance and Regulation, March 2014), http://www.cifr.edu.au/assets/document/CIFR%20Internationalisation%20of%20the%20RMB%20Report%20Final%20web.pdf.

The importance of these reforms for the internationalization of the RMB is hard to overstate. By the mid-2000s, China had become the largest trading nation in the world by dint of not only its trading relationship with the United States, but also its deep economic ties to Greater Asia and, as a commodities importing country, to Africa and South America. It was, in short, a leading exporter of goods, a regional trading hegemon, and an importer of natural resources. Opening the current account thus created a major channel for internationalization. Domestic exporters could avoid hedging and foreign exchange transaction costs by selling goods in RMB. Foreign companies, meanwhile, could gain a competitive advantage by selling goods to customers in their local currency—or receive discounts on purchases—as well as access a currency likely to appreciate.

Today, over 20 percent of China’s foreign trade is settled in RMB—up from just 3 percent in 2010,20Kathleen Walsh, RMB Trade Invoicing: Benefits, Impediments and Tipping Points(Canberra: Australian National University, 2014), p. 3, chart 1, http://www.treasury.gov.au/PublicationsAndMedia/Events/2014/~/media/Treasury/Publications%20and%20Media/Events/2014/RMB%20Dialogue/RMB_trade_invoicing_report.ashx. However, this is still low compared with around 50–60 percent of the eurozone’s external trade settled in euro, and 30–40 percent in yen for Japanese trade. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) expects RMB settlements to reach 30 percent by the end of 2015. and the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) estimates that the RMB is the second most commonly used currency in the world for trade finance and documentary credit transactions.21Sreeja VN, “Yuan Overtakes Euro as Second-Most Used Currency in International Trade Settlement: SWIFT,” International Business Times, December 3, 2013, http://www.ibtimes.com/yuan-overtakes-euro-second-most-used-currency-international-trade-settlement-swift-1492476. Notably, it would also create a powerful market mechanism for building up offshore RMB account liquidity as proceeds from commercial and trade transactions could be deposited and saved in deposit accounts in Hong Kong and eventually offshore financial centers in London, Singapore, and elsewhere. Energized by trade settlement and other official mechanisms, more than 900 billion in RMB deposits have accumulated in Hong Kong alone and over 1.6 trillion globally.22Barry Eichengreen, et. al., Internalisation of the Renminbi: Pathways, Implications and Opportunities, op. cit., p. 17.

Detriments of offshore RMB account liquidity

- Trade. Perhaps most commonly, an entity may be able to access the currency through simple current-account transactions. That is, a company may sell widgets to a firm in Beijing and receive RMB in exchange for the widgets.

- Foreign Exchange (FX). People, companies, and governments can also convert their euros and dollars, and other major currencies into RMB through FX transactions and deposit the proceeds in their accounts.

- On- and Offshore Capital Markets. Firms routinely access RMB via the sale of securities. For example, a company may do a bond offering (in the dim sum market or other offshore market) denominated in RMB and deposit the proceeds in an offshore bank account. These deposits may also be used to purchase securities.

- Cross-border Cash Pooling Structures. Increasingly, companies have the ability to move cash on- and offshore between affiliates and their accounts.

But note: As channels to move RMB onshore increase, they may draw on offshore deposit bases as companies put capital to work in China (see QFII, RQFII, and the two-way channels, discussed below).

Onshore investment channels: QFII, RQFII, and the Interbank Investment Program

China has also worked to liberalize its capital account domestically by offering foreign investors more access to its domestic capital markets—a process that when finished will rank as the most significant change in global capital markets in the last half century.

China’s domestic stock markets are younger than their Western counterparts, with both the two primary exchanges, the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, having opened in 1990. Since then, the country’s stock markets have developed rapidly, with the Shanghai exchange hosting larger, more developed corporate mainstays in ways analogous to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), and Shenzhen serving small, medium, and emerging growth (often technology) companies similar to NASDAQ. With roughly 2,500 companies between them, China boasts a stock market capitalization second only to the United States, though the liquidity and participation are well below those seen in the West. Both exchanges are regulated by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC).

Considerably more imposing than the equities market is China’s domestic bond market, which, according to some reports, is already the world’s third-largest, after the United States and Japan. Bonds trade on limited, overlapping markets. The interbank bond market (an over-the-counter market) accounts for 95 percent of volume and trades on a system called the China Foreign Exchange Trade System (CFETS). CFETS, which operates alongside ICAP, is regulated by the PBOC and the exchange markets by the CSRC.23Becky Liu, “China Onshore Bond Compendium 2014,”

Standard Chartered, April 29, 2014, p. 1, https://research.standardchartered.com/configuration/ROW%20Documents/China_onshore_bond_compendium_2014_29_04_14_07_34.pdf.

Fixed income securities like Chinese government bonds and bonds called enterprise bonds that are issued by central and local state owned enterprises can trade on exchanges. Recently, foreign issuers have been permitted to issue RMB denominated bonds onshore (called “Panda Bonds”), with the first being Daimler’s 500 million renminbi offering in March 2014. Foreign ownership accounted for 2.4 percent of Chinese government bonds, and 1.9 percent of the overall China’s bond market in 2014.

QFII and RQFII

Investors primarily rely on three channels to invest in the stocks and bonds listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, as well as over-the-counter bonds, investment funds, and other instruments. The first is the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII), which was established in 2002 and enables foreign investors to invest in China’s domestic capital markets using foreign currency obtained outside of China (usually US dollars).24Ibid. For investments to be legal, the CSRC is required to first approve an investment license for the prospective investor, after which the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) approves the quota limit. Non-sovereign sector investors are permitted a maximum quota of $1 billion under QFII, with a minimum application amount of $50 million. Since December 2012, the Chinese government has allowed sovereign investors to exceed a previously-set $1 billion investment quota limit. Sovereign QFIIs are also able to repatriate their principal and investment returns after a lock-up period of just three months, as long as the monthly remittances do not exceed 20 percent of the total onshore assets in the previous year.25As of end of 2014, twenty-seven sovereign entities have received quotas and are accessing the Chinese stock and bond market, including eight central banks, with over half having recently been approved for investing. And three sovereigns—the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Norges Bank, and Temasek—have now exceeded this limit. On the private side, BlackRock is one of the most aggressive players in the QFII space, and has received a quota allocation of US$600 million. Nearly US$72,149 million has been approved under the program.

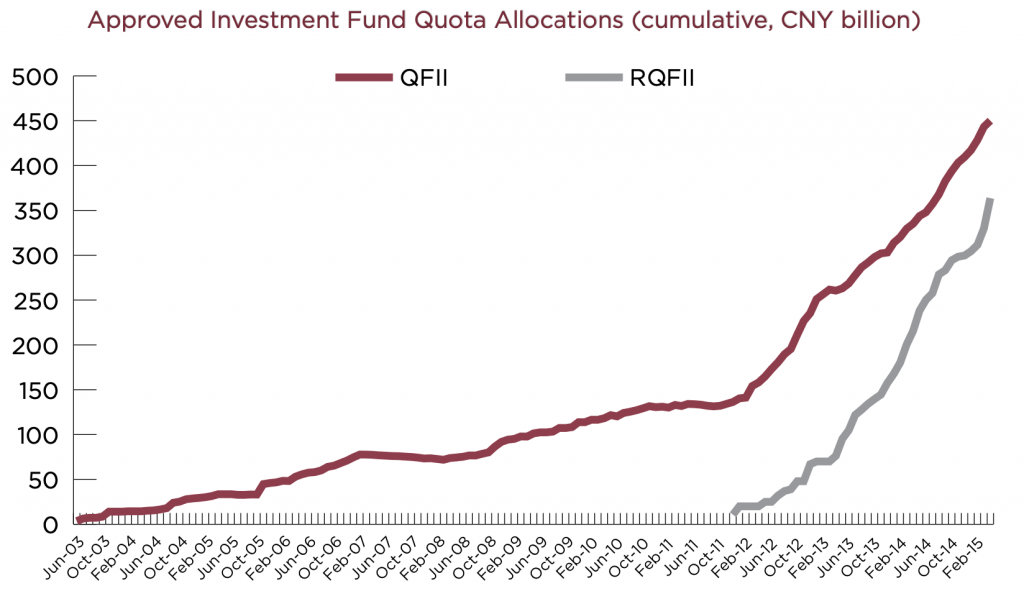

The foreign investment scheme was supplemented in December 2011 with the launch of RQFII. Under this program, foreign investors enjoy access to the domestic markets using RMB funding obtained from outside mainland China. Between these two formal programs, RQFII demand is by most accounts growing faster, with more than CNY 329 billion in RQFII quota allocated in just under four years. China is looking to increase connectivity with offshore markets by making it easier to obtain investment quotas and allowing wider investment scope to encourage two-way flows. Certain changes—including the introduction of a registration system for QFII and RQFII that may shorten the approval process for quotas, greater flexibility for QFII (i.e., becoming similar to RQFII), and the possible expansion of investment scope to include repos and derivatives such as interest rate swaps—are expected later in 2015.

The RQFII is also generally a more flexible scheme.26For an in depth comparison, see Becky Liu, “China Onshore Bond Compendium 2014,” op. cit., p. 25. Under QFII, the CSRC requires investors to devote at least 50 percent of their capital to equities and no more than 20 percent to cash, whereas the RQFII program currently imposes no such restrictions. Furthermore, QFII investors must repatriate their money in the form of the currency that they used to invest it, whereas RQFII can choose to repatriate in either RMB or foreign currencies. Both funds are, however, usually subject to a yearlong lock-up period. Where 70 percent of capital is invested in shares, however, no lock-up period is imposed under RQFII, and under QFII, lock-up periods are reduced to only three months.27Lock-up periods are also only three months long under QFII where pension funds, insurance funds, charity and endowment funds, governments, and sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) make investments. Ibid.

Interbank Investment Program

The final initiative of note is the interbank investment program, overseen by the PBOC, which gives foreign investors direct access to China’s onshore interbank bond market within a quota assigned by the central bank. It offers the greatest flexibility of the three programs, but is limited to six types of foreign investors: foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, RMB clearing banks, RMB settlement banks, supranationals, and insurance companies.28Ibid. Part of its breadth is due to the fact that the program aims, above all else, to support internationalization and is not a first order scheme for channeling foreign direct investment, even though November 2013 statistics show that a total of CNY 600 billion of the quota had been assigned to 138 investors. The program’s primary criticism is, however, that it lacks transparency.29Ibid. Requirements relating to applicants’ financial profiles and regulations concerning the repatriation of funding—along with approved investment quotas—are not publicly disclosed.

Note: Reforms for Asset Managers

Though still viewed as largely symbolic given the relatively limited liberalization offered, other less well known alternatives modeled in part after RQFII and QFII, including the Qualified Domestic Limited Partnership (QDLP) program, may gain more prominence. The program, launched in April 2015, enables overseas asset managers to establish qualified domestic private RMB funds, domiciled in Shanghai, to invest into offshore securities markets. In the first iteration of the program, however, only six hedge fund managers received quotas of $50 million each. A similar pilot program, dubbed the Qualified Domestic Investment Enterprise (QDIE), was introduced for Shenzhen in 2014.

Offshore RMB investment via the offshore RMB bond market

Alongside a domestic bond market, an offshore RMB market has been launched to support the internationalization process. As with many currencies in the past, offshore markets are useful and, in some instances, necessary conduits for recycling currency through the global financial system. For China in particular, offshore markets allow holders of the currency to put their money to use as an investment. Opening deposit accounts and the current account creates a channel for pushing liquidity abroad. But for it to stay there, there must be a counterparty willing to hold it.30Barry Eichengreen, et. al., Internalisation of the Renminbi: Pathways, Implications and Opportunities, op. cit., p. 100. Otherwise, the exporter will simply convert RMB into another international currency or its home currency, especially where, as has been the case, restrictions have been placed on investing money onshore due to the volatility and risk that cross-border capital flows can create.

The most important channel outside of China for RMB-denominated investment has traditionally been the “dim sum market.” Though the term can have varying connotations, dim sum bonds are largely understood to be commercial and government bonds issued outside China in the international market (thus in Hong Kong and elsewhere) but denominated in offshore RMB. As a result, there are no restrictions on the use of proceeds unless companies seek to repatriate the funds onshore.31Though even here, rules have weakened dramatically. New FDI rules introduced in March 2012 have made it easier to issue CNH bonds and bring the proceeds onshore, as have new innovations like the cash pooling made available in the SHFTZ. Bond covenants are also notably subject to the global standard, and Hong Kong boasts an internationally recognized legal framework for resolving contractual disputes and running insolvency proceedings.32Yin Wong Cheung, “The Role of Offshore Financial Centers in the Process of Renminbi Internationalization,” inBarry Eichengreen and Masahiro Kawai eds., Renminbi Internationalization, Achievements, Prospects and Challenges(Tokyo and Washington, DC: Asia Development Bank Institute and Brookings Institution Press, 2015), p. 216.

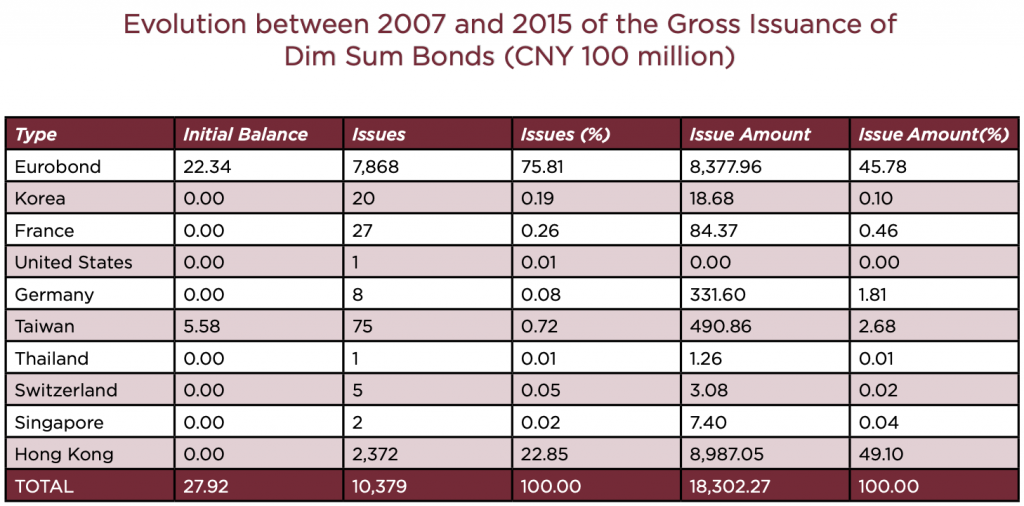

RMB bonds began to trickle cross border in 2003, as reforms in deposit taking and personal banking services were introduced. The offshore RMB-denominated bond market was, however, officially inaugurated in July 2007, when China-based firms, led by the China Development Bank, were permitted to issue bonds in Hong Kong. Then, in July 2010, the Chinese government gave foreign, nonfinancial companies the right to issue RMB-denominated bonds outside of China’s otherwise closed capital markets.33John Maxfield, “How Dim Sum Bonds Will Change the World,” Motley Fool, February 10, 2012, http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2012/02/10/how-dim-sum-bonds-will-change-the-world.aspx. The first foreign multi-national company to successfully secure permission from the government and take advantage of the program was McDonald’s, which raised CNY 200 million one month later. Today, the dim sum market is mostly dominated by small, denominated, and short-term issuances; however, a number of major market participants have issued offshore securities—from the Chinese Construction Bank and state-owned enterprises like Shanghai Baosteel to foreign financial institutions and corporations like Standard Chartered Bank and Caterpillar Financial, respectively. The Ministry of Finance has also issued longer term bonds of thirty years to set up an offshore market yield curve.34Yin Wong Cheung, “The Role of Offshore Financial Centers in the Process of Renminbi Internationalization,” op. cit., p. 216.

In just five years, the dim sum market has emerged as a viable funding option for corporations, regardless of their size. And the market’s growth has been, in many ways, explosive.

The expansion of the offshore bond market can be attributed to several factors. First, increasingly large pools of RMB liquidity were located offshore since the mid-2000s—made possible by reforms relating to trade settlement, discussed above, and related growth in offshore deposits. Second, investors had few channels through which to invest in either Chinese companies or the RMB itself. Government programs (like the QFII program, discussed below) permitting foreign investors to directly invest onshore or repatriate profits or cash onshore were limited or not yet in existence, leaving offshore bond markets to be the only practical outlet for RMB-denominated investments in many instances. Many issuers did not complain, since offshore interest rates were often lower than onshore rates, just as the RMB traded at a premium vis a vis the US dollar. So as offshore RMB grew, banks quickly began redeploying their proceeds in the dim sum market.

Still, recent data indicate that many of the structural tailwinds in place at the inception of the dim sum market are now reversing course. Intervention by the Chinese government to hold down the yuan, along with a steady appreciation of the US dollar, have curbed the RMB’s appeal. This has in turn contributed to a shortage of yuan offshore, which drove up general borrowing costs as well as the costs for borrowing RMB in the cross-currency swap (CCS) market.35One particular challenge is that, as liquidity has dried up, the yields on cross currency swaps have increased and with them the cost. This in turn may have a negative impact on the dim sum market, since foreign investors heavily rely on CCSs to borrow RMB-denominated money for use in purchasing dim sum bonds. Meanwhile, the onshore bond market is becoming more attractive to issuers and more available to foreign investors. Chinese regulators have, among other things, reduced reserve ratio requirements, allowing banks to make more investments at less cost for borrowers. Moreover, the PBOC has lowered interest rates to stimulate the sagging Chinese economy, moving onshore and offshore rates closer together.

At the same time, and critically, an increasing array of channels became available for the onshore repatriation of offshore funds after existing quotas allocated to foreign investors increased (see RQFII, QFII, and Interbank programs discussed below). A series of new programs is also in development, aimed at increasing the ability of investors to put their capital to work onshore (see HK-SH Stock Connect and two-way cash pooling, discussed below). Though these factors all help to promote the RMB, they have at least partially muted the short-term effect of reducing the luster of the offshore bond market and the offshore deposit system.

Nevertheless, even as interest rates and currency valuations have in some instances converged, the dim sum market offers a number of important advantages over the onshore market for foreign investors. Perhaps most importantly, offshore RMB investments are not subject to lock-up periods (and thus are distinguishable from RQFII and QFII) and can be repatriated anywhere without government intervention as long as they are not channeled back into China; moreover, investments escape many of the capital gains taxes applied onshore. Thus, investors enjoy more flexible cash management and more favorable tax treatment. The dim sum market is also adapting to make itself more attractive to foreign investors over the longer term. The dim sum market has been criticized since its inception for a relative absence of rated products. Consequently, participants have worked assiduously to increase the number of rated, fixed-income products as a more mature market has emerged that is as concerned with credit risk as currency appreciation. More ratings have in turn opened a pathway for more foreign institutional investors and funds to participate in China’s economic growth.

Additional (two-way) investment channels: The Hong Kong-Shanghai stock connect, cash sweeping, and free trade accounts

In addition to programs offering targeted paths for investors to channel RMB investment money into targeted offshore programs (like the dim sum market) or specifically into the mainland (via QFII and RQFII), other programs offer flexibility for bilateral flows of RMB and investment both on- and offshore.

The Hong Kong-Shanghai stock connect

The first is the Hong Kong-Shanghai Stock Connect program, which allows global investors to buy Shanghai-listed shares through Hong Kong and investors on the mainland to trade Hong Kong-listed shares through Shanghai. Under the terms of the program, investors can trade eligible shares listed in Shanghai by routing orders through Hong Kong brokers and a securities trading service established by the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Meanwhile, eligible investors in China will be able to place orders with the help of local brokers and a firm established by the Shanghai Stock Exchange to trade shares listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. The China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation and the Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company will clear the transactions.36ASIFMA, Standard Chartered, and Thomson Reuters, RMB Roadmap, op. cit., p. 24.

The program presents an unprecedented opportunity for retail investors outside China to trade Chinese stocks alongside their more sophisticated institutional counterparts.37ASIFMA and Thomson Reuters, The Through Train: Stock Connect’s Impact and Future (December 2014), p. 9, http://share.thomsonreuters.com/assets/forms/shanghai-hk-stock-connect-1008885.pdf. However, trading has been slow by many measures, in part due to regulatory controls on the capital account, which have undermined the program’s short-term effectiveness.38Under the program, CNY 13 billion flow north into mainland equities each day and CNY 10.5 billion head south. The opening days of the program saw, however, a net departure of capital from Hong Kong to Shanghai and a draw of funds from offshore deposits and the dim sum market. As a result, HKMA is setting up a CNY 10 billion intraday repurchase facility and seeking to relax a cap on RMB purchases by the city’s residents before local investors gain access to Shanghai’s stock market to help smooth intraday money-market volatility. See Saikat Chatterjee, “CNH Tracker-Stock Connect Scheme Reduces Dim Sum Issuers’ Costs,” Reuters, November 20, 2014, 2:34 a.m., http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/11/20/markets-offshore-yuan-idUSL3N0T937X20141120. Shanghai’s settlement system for stocks differs from that of many international counterparts. Investors selling A-shares have had to initially “pre-deliver” their shares to brokers on the day prior to the trade, generating settlement risks because investors have two days between the delivery of their shares and receipt of payment. Furthermore, once the quotas under the program are reached (CNY 13 billion for northbound investors and CNY 10.5 billion for southbound investors), buy orders are prohibited, and investors are only permitted to sell.39ASIFMA and Thomson Reuters, The Through Train: Stock Connect’s Impact and Future, op. cit., p. 9. Similarly, once a government-imposed limit of 10 percent foreign ownership of any one stock is breached, a forced sale procedure is undertaken at the end of the day. With such risks, hedge funds, as opposed to longer-term, risk-averse investors (who have largely continued to rely on QFII and RQFII) have been the first to enter the market.40Ibid.

The lack of cross-border coordination also stymied the launch. Although an unprecedented degree of cooperation between the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) was necessary to get the program off the ground, there was limited coordination with other offshore financial authorities in London and Luxembourg.41Among the necessary measures was an unprecedented memorandum of understanding (MOU) concluded between the CSRC and the SFC, establishing a basis for cooperation on issues including market surveillance enforcement coordination and information sharing. Ibid., p. 6. As a result, concerns about the ownership rights of shares subject to pre-delivery caused authorities to temporarily delay permitting funds from investing in the link.42Michelle Price and Saikat Chatterjee, “Exclusive: EU Regulatory Concerns Curb China Stock Link Volumes, Reuters, November 28, 2014, 4:40 a.m., http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/11/26/us-hongkong-china-stocks-exclusive-idUSKCN0JA0WY20141126. Furthermore, European fund managers were only given one week’s notice concerning the start date of the program, delaying their participation since many needed client approval before proceeding. This delay slowed the impact of the capital account reforms.

That said, the program is still widely hailed by market participants and commentators as a breakthrough. Already capital flows have increased dramatically with more buoyant stock markets, especially on the mainland. And over time, it will serve as a major conduit for two-way portfolio investment. With investment portfolios underweight in China-related investments, most experts expect the existing quotas to be quickly surpassed once initial regulatory hurdles are addressed. Furthermore, additional programs like the Stock Connect are under consideration—not only with Shenzhen’s exchange for early stage companies, but also with exchanges in Europe and Asia. Similarly, SFC and the CSRC have initiated a potentially pathbreaking mutual recongition program between Hong Kong and China investment funds. Still, concern is growing as China’s historic equities bull market run continues at least in part on the back of accommodative Chinese monetary policy. If the market was, in short, to suddenly falter or crash, not only could foreign investors become more tepid in their approach to investing in China, but Chinese regulators too could slow the pace of liberalization and reform.

Two-way cash pooling and RMB sweeping

Another key program involves so-called “two-way cash sweeping” for multinational corporations to enable more efficient cash management. In 2013, the PBOC allowed companies registered in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ) to remit working funds across the border and thus extend RMB intercompany loans to their offshore parent companies, subsidiaries, or affiliates.43Deutsche Bank, At the Centre of RMB Internationalisation: A Brief Guide to Offshore RMB (2014), p. 24, https://www.db.com/en/media/At-the-centre-of-Renminbi-internationalisation–A-brief-guide-to-offshore-RMB.pdf. Since then, the program has evolved into a two-way cash sweeping tool, allowing funds to be reallocated in and out of the country.

The RMB sweeping program is widely hailed as one of the most important reforms under the SFTZ. Prior to the reforms, China-based companies required regulatory approval to borrow funds from overseas, and a foreign investment enterprise could exhaust quotas imposed by the government on the amount of debt it could borrow abroad (called a “foreign debt quota”), at which point they would be forced to borrow from onshore banks, where liquidity was not always stable, especially as the economic growth slowed. Today, companies can effectively compare offshore and onshore rates and remit excess liquidity via intercompany loans and transfers for operating use where needed. Moreover, firms can bring money in and out of the country while circumventing many restrictions of the RQFII and QFII programs, such as lock-up periods.44Note there is also a leasing model, like the sweeping system, with no use-up of the quota and thereby enabling registered leasing companies to firms to access up to ten times their capital. This has been a popular route of bringing capital into the company.

Notably, the Chinese government has also introduced a pan-China program with similar aims. Under the new scheme, participating corporations in the same group will have access to many of the same benefits afforded under the SFTZ. To be eligible, each onshore affiliate company needs to have operated for at least three years in China, and the same amount of time applies to each offshore firm operating overseas. Furthermore, the sales turnover of the previous year needs to be at least CNY 5 billion for onshore participating companies and CNY 1 billion for offshore affiliates.45Kevin Lau et. al., “Offshore RMB–Slowly Emerging from a Soft Patch” Standard Chartered, November 7, 2014, p. 10, https://research.standardchartered.com/configuration/ROW%20Documents/Offshore_RMB_%E2%80%93_Slowly_emerging_from_a_soft_patch_07_11_14_05_39.pdf.

Free trade accounts

A third imminent reform, also tied with the SFTZ, is the availability of so-called “free trade” accounts for Chinese residents and foreign companies. Under the pending reforms, the accounts will be treated like bank accounts outside of China. Thus, holders of the free trade accounts will be able to move funds offshore and, “when the time is ripe,” use them for unrestricted foreign exchange transactions.46Jeanny Yu, “Proposals Announced to Boost Shanghai Free Trade Zone,” South China Morning Post, December 2, 2013, 11:37 p.m., http://www.scmp.com/business/economy/article/1371388/proposals-announced-boost-shanghai-free-trade-zone. Holders will also be able to move funds to nonresident bank accounts in China but outside of the free trade zone.47Barry Eichengreen, et. al., Internalisation of the Renminbi: Pathways, Implications and Opportunities, op. cit., p. 32. Prior to the reforms, individuals or companies outside the free trade zone were required to seek approval from SAFE or show documented evidence for large payments, demonstrating that they are lawful (usually current account) transactions. As such, the reforms are viewed as particularly significant.48Hogan Lovells, “China Streamlines Foreign Exchange Administrative Procedures to Facilitate Cross-Border Investments,” March 2013, p. 4, http://www.hoganlovells.com/files/Publication/a8424594-eb7a-41da-a907-003617097867/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/2596e344-6d67-4ac2-8c8b-6dc339366d8b/Hogan_Lovells_Client_Alert_-_China_Streamlines_Foreign_Exchange_Administrative_Pro.pdf. According to recent reports, five mainland banks have already received a permit, including three of the Big Four state lenders—Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and China Construction Bank—as well as Shanghai Pudong Development Bank and Bank of Shanghai.49George Chen and Jeanny Yu, “Foreign Banks in Shanghai Free-Trade Zone Lack Permits to Transfer Funds Freely,” South China Morning Post, July 8, 2014, 11:58 a.m., http://www.scmp.com/business/banking-finance/article/1549490/lack-permit-stalls-ability-foreign-banks-ftz-branches. Ten foreign banks have opened subsidiaries in the zone and are expected to receive accounts by mid-2015.

What’s the Shanghai Free Trade Zone?

The SFTZ was launched September 29, 2013 by Premier Li Keqiang as both a mechanism and symbol of the country’s commitment to economic reform. In the SFTZ, Chinese officials plan to administer a range of liberalization efforts—in areas as diverse as trade, intellectual property, interest rates, and the cross-border flow of capital—and, where successful, gradually export the reforms to rest of the country.

Official support for the RMB

Although often compared to the eurodollar market, the offshore RMB market is a qualitatively different project in many ways given the deep levels of proactive Chinese government involvement and control over the process. The eurodollar market, for its part, was an initiative largely privately run by banks seeking to escape tax equalization charges. As discussed above, the offshore RMB market, by contrast, has involved targeted state-run efforts to gradually open the capital account alongside a comparatively more concerted effort to pen the current account. Offshore liberalization has also included a series of novel applications of existing statecraft to promote the internationalization of RMB and development of offshore pools of RMB liquidity

Bilateral swap agreements

Among the most important and publicized channels of “exporting” the RMB have been bilateral swap agreements with other central banks. Under a program launched in 2009, the PBOC has agreed to extend three-year lines of liquidity support for selected central banks. The lines can be drawn on and deployed to increase market stability or downstreamed to domestic banks. In the former case, creating a line of liquidity allows central banks to supply banks participating in RMB markets with emergency or intraday liquidity should the need arise; in that way, central banks can provide a bulwark against potential runs. In the latter case, a foreign central bank establishes facilities for trade or investment financing by offering long-term RMB denominated loans for qualifying domestic financial institutions so that offshore funding demands can be met locally. China has also, notably, joined neighboring countries in launching what is today known as the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM)—a series of swap lines backed by foreign reserve pools of $240 billion for countries facing balance of payments crises. Part of the initiative’s agenda includes diversifying swap lines to include the RMB.

Development loans

Another important channel has been through international development and assistance programs. As early as 2011, the China Ex-Im Bank began to work alongside the Inter-American Development Bank to establish an RMB-based fund to support investments in Latin America and the Caribbean.50Paola Subacchi and Helena Huang, “The Connecting Dots of China’s Renminbi Strategy: London and Hong Kong,” op. cit., p. 6. And more recently, in 2014, China established the New Development Bank (NDB) alongside Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa (initially styled the BRICS Development Bank).51Hongying Wang, From “Taoguang Yanghui” to “Yousuo Zuowei”: China’s Engagement in Financial Minilateralism, Cigi, December 2014, No. 52, p. 1, https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/cigi_paper_no52.pdf. According to commentators, the $50 billion of subscribed capital for the new bank aims to mobilize resources to invest in infrastructure and sustainable development projects in member countries. It also aims to do so through local currencies.52Ibid. In this way, the NDB not only works to incrementally decrease countries’ reliance on traditional multilateral sources of assistance like the IMF, but also to promote alternative currencies—and most importantly the RMB. Similarly, China has signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) establishing a $100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which likewise supports Asian infrastructure projects. AIIB is intended to not only promote closer relations in the region, but also the internationalization of the currency.53Ibid Though still in the early stages, the bank has won plaudits from some governments, including the United Kingdom, which announced plans to join the bank despite US skepticism and charges of “constant accommodation” of Chinese political interests. Since then, other European countries including Germany, France, and Italy have announced their intentions to join the bank.

Clearing banks

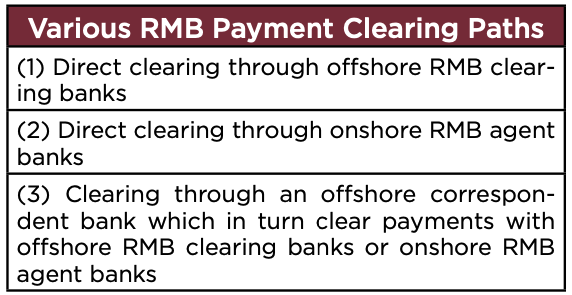

The Chinese government has also played an important role in supporting the RMB by publicly nominating specially designated, offshore “RMB clearing banks,” and by implicitly standing by the liquidity they provide. China has furthermore granted agent bank licenses for banks in China as an alternative to clear RMB payments overseas. Clearing generally refers to the activities involved in confirming, monitoring, and ensuring that sufficient collateral or margin is provided where required, until a trade is actually settled (i.e., monies exchanged between transacting parties).

A list of offshore RMB clearing banks nominated by the PBOC is provided below:

Apart from directly routing RMB payments to an official offshore clearing bank or a PBOC-licensed onshore agent bank for clearing, offshore RMB payments initiated from any offshore commercial bank can also be routed to a correspondent bank that transacts with an RMB agent or clearing bank for clearing via the Chinese RMB payment system.

However, onshore liquidity can be a constraint for banks mediating the transaction, since cash from the PBOC can often only be withdrawn at 9:00 a.m. the following day.54Swift, “RMB Internationalisation: Perspectives on the Future of RMB Clearing,” p. 4, http://www.swift.com/resources/documents/SWIFT_White_paper_RMB_internationalisation_EN.pdf. Thus, routing through correspondent banks instead of using direct clearing may take extra link without the implicit promise of enjoying direct liquidity support from the PBOC.

The offshore clearing bank model was introduced in 2003, when the Bank of China (Hong Kong) Ltd was appointed by the PBOC as the first clearing bank for offshore RMB.55Ibid. This model was then given a boost (see discussion below) when the Bank of China Hong Kong engaged Hong Kong Interbank Clearing Limited to develop a settlement system that operated in real time for offshore transactions. Since then, clearing banks have been established throughout Asia and Europe, and some financial centers are developing world-class RMB settlement systems on their own.

It is worth noting, however, that the advantages of official support for clearing banks may be, above all, political. In many ways, designated clearing banks do notnecessarily perform any functions beyond those of correspondent banks. Like Western banks, they can facilitate RMB payment to beneficiaries of payments and participate in FX deliverable markets to access the currency where needed. Most clearing banks even had to connect with China National Advanced Payment Systems (CNAPs) through an affiliate in China. But they do provide an opportunity to provide a bricks and mortar face for RMB internationalization to clients and customers who may be unfamiliar with the currency. This in turn increases overall awareness of the RMB, heightens foreign interest in the currency for trade and investment purposes, and raises the profile of the country hosting the bank as an international financial center.

The global growth of RMB financial centers

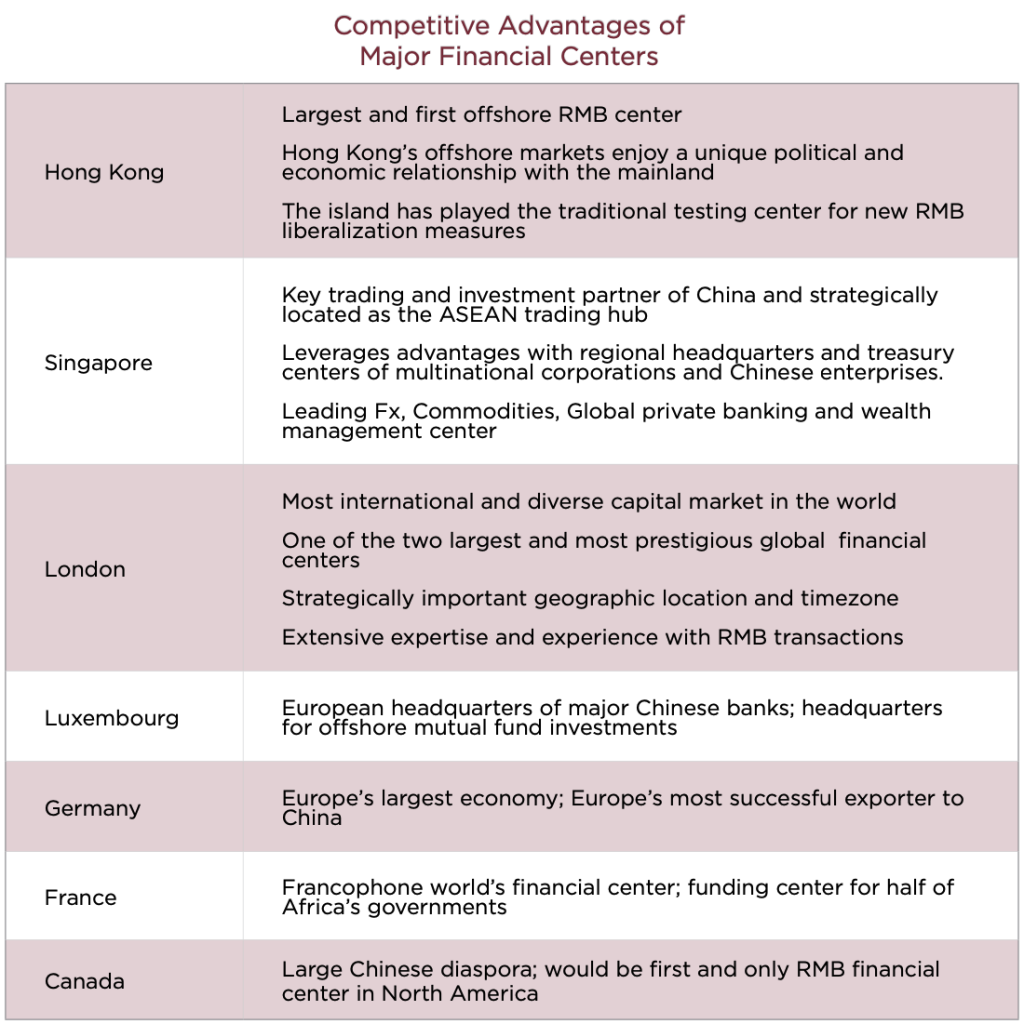

Hong Kong was a natural first stop for the internationalization process. Besides being part of China (albeit with a separate legal and financial system), its geographic location, and its international expertise and connections, Hong Kong hosts a multi-currency settlement infrastructure underpinning its role as one of the world’s leading international financial centers. As a result, Hong Kong as a special administrative region (SAR) still receives the majority of investment quotas and is often the locale of choice for pilot programs that, when successful, are exported to the rest of the world.

Hong Kong boasts a real time gross settlement system (RTGS) to facilitate settlement of foreign exchange transactions on a payment-versus-payment basis, a Central Clearing and Settlement System (CCASS) to settle equity transactions on a delivery-versus-payment basis, and a Central Moneymarkets Unit (CMU) to clear bonds and investment fund shares. There is now a regular CNH Hong Kong Inter-Bank Offered Rate (HIBOR), overseen by the Hong Kong Treasury Markets Association and covering tenors from overnight to one year to facilitate the pricing of offshore RMB-denominated loans and derivatives for risk-management purposes. Also, Hong Kong’s favorable tax rates for business transactions with no corporation withholding taxes for monies remitted to nonresidents and the presence of a large number of double taxation treaties with foreign governments make it a preferred place of business. Not to mention its strong rule of law, contract enforcement, and the presence of a common law system inherited from Great Britain make Hong Kong a top-rated location for economic and business freedom. Finally, Hong Kong hosts a native Chinese population, a large number of mainland companies, and considerable daily population movement across the border with mainland China.56Barry Eichengreen, et. al., Internalisation of the Renminbi: Pathways, Implications and Opportunities, op. cit.