To many, the European Union (EU) is a complex entity overburdened by rules. In The European Union Could Be Simple, Inclusive, or Effective. Pick Two., author Dimiter Toshkov, an associate professor at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University, presents the structural dilemma facing the EU: accommodating the diverse interests of twenty-eight member states while delivering effective policies for over 510 million citizens in a simple way.

As part of the Atlantic Council’s “EuroGrowth Initiative,” the policy paper examines why the Union’s system of government is so complex and how said complexity affects the effectiveness and ability of the EU to solve common problems. Only citizens who understand how the EU works will trust it to deliver policies that can support economic growth across the continent and respond to global challenges.

The European Commission included regulatory simplification as one of its ten priorities for the current term, launching the “Better Regulation” program. Dimiter Toshkov examines the program’s progress, as well as other options to achieve simplification, such as informal agreements between different EU bodies and more radical action through treaty reform.

Key recommendations

- The EU should focus on adopting fewer legislative acts, instead prioritizing those that have clear and tangible value for Europeans, have less discretion to the member states, and are enforced more consistently across member states.

- The EU should aim to simplify the message it projects about its own identity, be more clear about the fundamental values for which it stands, and be more consistent in the promotion of these values with its policies and actions.

- The EU should be more transparent about the way EU policies are made and enforced.

- All EU citizens, and particularly young people, should have the opportunity over the course of their education to learn basic facts about how the EU works.

- The EU should focus on adopting fewer legislative acts, instead prioritizing those that have clear and tangible value for Europeans, leave less discretion to the member states, and are enforced more consistently across member states.

This publication is part of the Atlantic Council’s EuroGrowth Initiative. The EuroGrowth Initiative is made possible by generous support from Beretta, the European Investment Bank, Moody’s Investor Service, Pirelli Tire North America, United Parcel Service, Inc. (UPS), Ambassador C. Boyden Gray, and Ambassador Stuart Eizenstat.

Introduction

“Simple” is not a word you hear often when people talk about the European Union. On the contrary, in the minds of many, the EU embodies the exact opposite of simplicity: a Kafkaesque labyrinth of agencies, committees, and commissions; a bureaucratic monster spawning red tape and ludicrous regulations about the shape of bananas and the like.

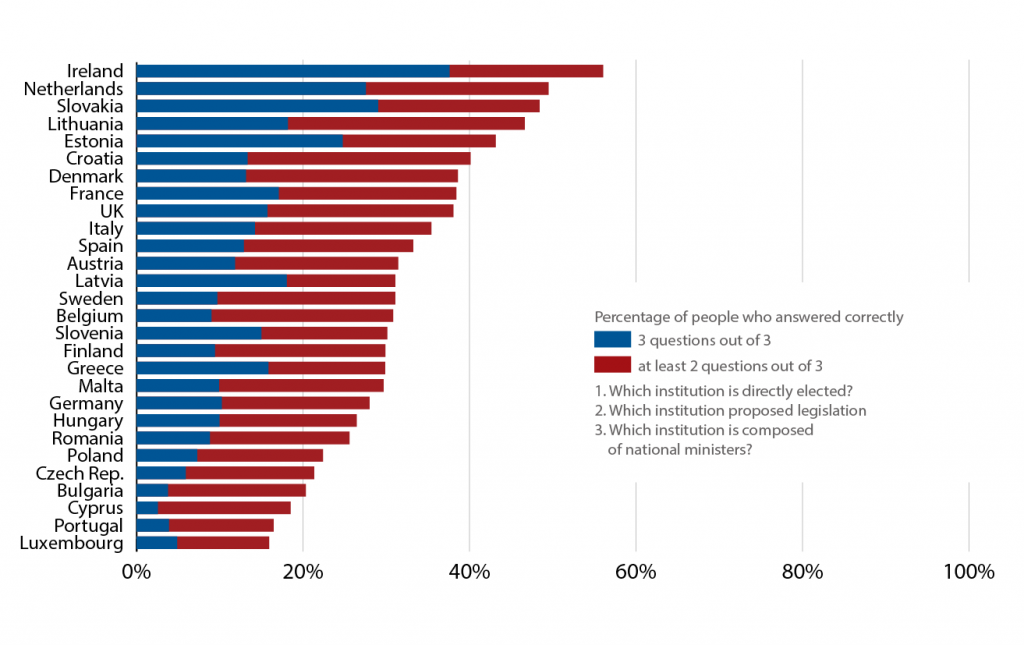

These images might not be entirely fair, but they are pervasive. There is no denying that European citizens have little idea about what the various EU institutions actually do (see Figure 1), and even seasoned politicians might struggle to understand the EU’s decision-making procedures.1For example, the British Secretary of State for Leaving the European Union David Davis apparently did not know that EU member states do not negotiate trade deals individually, but as a block (for details, see the analysis by Mark Munger on the EUROPP blog, http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/07/18/david-davis-brexit-trade-agreements/). It is hard to blame them (the citizens at least). It is not easy to explain why the EU has three presidents2These are the president of the European Commission, the president of the European Council, and the president of the European Parliament. One could also add the country holding the presidency of the Council of Ministers of the EU, the president of the Eurogroup, and the president of the European Central Bank. at any one time, why the European Parliament (EP) cannot draft its own proposals for new laws, or why all 751 members of the EP relocate for a week every month from their usual workplaces in Brussels, Belgium to Strasbourg, France, dragging with them their entourage, the EP’s secretariat, and all associated paperwork on the way there and back.

The EU is complex. The policies it makes and the institutional rules by which it makes these policies are complex, too.3Even leaving the EU is extremely complex, as the United Kingdom (UK) is finding out at the moment.

Complexity is not necessarily bad. It is the price to pay to have an inclusive organization that accommodates the diverse interests of its twenty-eight members to the greatest extent possible while delivering effective common policies, when feasible.

Hence, in principle, there are only two ways to achieve radical simplification of the institutional setup of the EU and the regulatory environment in Europe. On the one hand, the EU can remain effective and be made simple, but that entails the sacrifice of the inclusive, accommodating, and consensual character of its institutions and decision-making procedures. For example, plurality voting rules are simple and allow for effective decision-making, but they can leave a majority of the participants outvoted and unhappy with the outcome. On the other hand, the EU can remain inclusive and be made simple, but that would hinder its ability to find potential areas for further integration and deliver effective compromises in the face of disagreements between the member states. For example, unanimity voting rules are simple and inclusive (as no participant can be outvoted), but they also drastically hamper decision-making effectiveness (as very few decisions can be agreed upon by all).

Neither of these two ways of simplifying the EU looks feasible for the time being. Both would require changing existing EU treaties, which in and of itself is an extremely complex procedure with a highly uncertain outcome, given a lack of strong popular and political support for such reforms.

Figure 1. Public knowledge about EU institutions is low

Consequently, in the near future, it is as improbable that the EU will become radically simpler as it is unlikely that people would suddenly start to appreciate the Byzantine complexity of its institutions.

What European politicians should try to do, however, is aspire to make the EU more modest about its own importance and more transparent. The EU must present a simpler and clearer message about its identity. Perhaps it does not even need to have a simple institutional setup in order to be liked and trusted by the populations of its member states. However, the EU definitely needs to be clear about the fundamental values it embraces, and consistent in the promotion of these values with its policies and actions. It must focus its regulatory attention only where common European rules bring real added value to European citizens, and then make sure that these rules take effect and have a meaningful, positive impact. The EU also needs to be more transparent about how European laws and policies reflect and arbitrate between the diverse national, political, and societal interests in the EU.

Why is the European Union complex?

The institutional setup of the European Union is complex for three main, and related, reasons: historical legacies, the need for compromise, and flexibility.

Legacies

The European institutions were born out of the need to foster economic and political cooperation between sovereign nation-states with a long history of ruinous conflicts among them. To facilitate cooperation among these sovereign nation-states, compromises had to be made. These compromises were embodied in institutional arrangements necessary to get the nation-states on board with the European project, but appear glaringly inefficient from today’s point of view. The multiple seats of the EP, the requirements for supermajorities to pass legislation, and the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU provide examples of the cumbersome accommodations made. Once agreed upon, these compromises were enshrined in the founding treaties of the EU, making them extremely difficult to change. Eventually, the member states made new arrangements to remedy some of the most evident inefficiencies of the original institutions. However, this only led to, yes, even more complexity.

For example, the presidency of the EU Council of Ministers has rotated among the EU’s member states every six months since 1958. In order to ensure a greater degree of continuity in the work of the Council from one presidency to the next, since 2007 the member states have cooperated in groups of three successive presidency holders (the so-called “trios”). In 2009, the European Council4The European Council is composed of the heads of state or government of the EU member states, and it has been recognized formally as an official institution since 2009. Its operation, however, has remained closely linked with the work of the different configurations of the Council of Ministers of the EU. acquired its own president, a position currently held by the Polish Donald Tusk, which changes only every two-and-a-half years. In addition, since 1998 the finance ministers of the member countries of the Eurozone have met in a special formation of the Council (the so-called Eurogroup), which since 2004 has been chaired by its own president, currently the Dutchman Jeroen Dijsselbloem. Ultimately, the original institution of the Council of Ministers that was designed back in the 1950s for a community of six member states cooperating on a narrow set of issues was never replaced by a simpler and more efficient solution, but was rather supplemented with additional rules and arrangements that have made the EU even more complex. Yet, these complex institutions have made it possible for the EU to continue to operate with a much larger set of ever more diverse member states and an expanded agenda of issues to deal with.

When judging the complexity of today’s EU institutions, bear in mind that they are reflective of the difficult deals made decades ago, and exacerbated by several layers of successive add-ons and adjustments that increased with every accession to the EU.

Compromises

Overlapping, multi-layered, multi-level institutions might be slow and cumbersome, but they are well-suited to accomplish what the EU needs most: finding potential areas for further cooperation and patches of common ground on which to build joint policies and actions. In addition to the weight of historical legacies, the need to find compromises between states with only partially aligned interests begets institutional complexity. For example, the EU has a complex system of committees, part of the Council of Ministers, composed of national civil servants representing their respective countries, that negotiate the content of new EU legislation in particular areas, such as development cooperation, telecommunications, or forestry. These so-called “working parties” are crucial for identifying areas of disagreements between the member states over the legislative proposals made by the European Commission, drafting compromises, and preparing the final decisions that the national ministers then formally adopt. Currently, more than 150 of these working parties are active, and recent estimates suggest that there have been more than 75,000 meetings of Council working parties between 1995 and 2014. Yet, despite their importance, the role of working parties remains relatively obscure and their effectiveness unappreciated5.For a recent analysis of the role of working parties, see the post by Frank Häge on the EUROPP blog, http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/08/29/data-on-political-attention-in-the-council-illustrates-the-eus-failure-to-proactively-address-major-crises/.

Flexibility

Historical legacies and the need for compromise go a long way toward explaining the institutional complexity of the EU. The necessary compromises result in discretion and flexibility that, in their turn, lead to high regulatory complexity. To accommodate all member states, EU legislation typically allows for numerous exceptions, exemptions, derogations, transitional periods, and other forms of discretion left to the member states. One important type of EU law—the directive—needs to be adapted to national circumstances through a separate national legislative act in a process called “transposition” before it acquires any real effect.6The directive is a type of legislative act in EU law that has general application and is binding as to the result to be achieved, but leaves the choice of form and methods of implementation to individual member states, who must transpose the directive’s obligations into national law within a given deadline (typically, two years). In addition, the lack of a strong, centralized enforcement capacity at the EU level means that member states often enjoy a great degree of flexibility when it comes to when and how to apply EU rules on the ground.

All this flexibility decreases regulatory certainty and does little to create a level playing field in Europe. Yet, it is necessary in order to win the consent of the member states for approving EU laws at the decision-making stage. Simply put, if EU directives did not grant so much flexibility, concessions, and discretion to the member states, they would not be adopted in the first place.

Flexibility increases complexity in yet another, more consequential way. Flexible forms of integration allow some states to proceed with further integration without having to wait for the agreement of the rest of the EU members. The Eurozone7The Eurozone, or Euro area, is comprised of the nineteen member states of the EU that have adopted the euro (€) as an official currency. In addition to the common currency, the Economic and Monetary Union involves a common monetary policy and coordination of economic and fiscal policies. Seven EU member states could join the Euro area if and when they fulfill the so-called “convergence” (economic, monetary, and fiscal) criteria. The remaining two–the UK and Denmark–have negotiated opt-outs from the Eurozone. and the Schengen Agreement8The Schengen Agreement, first signed in 1985 and later incorporated under the EU framework in 1997, guarantees free movement of persons in the territory of the Schengen Area. The participating states have abolished internal borders, apply common rules to issues such as short-stay visas, asylum requests, and border controls, and support cooperation between their police services and judicial authorities. are the most prominent examples of integration projects where not all EU member states participate, and some non-member states participate, exemplified by the membership of Norway, Switzerland, and Iceland in the Schengen Area.

There are further cases of flexible (or, as it is technically called “enhanced”) cooperation on policy issues such as divorce law and patents, in which several EU member states have decided to move forward with integration, while others have decided not to participate.

The most important recent cases of flexible integration concerned the adoption of the Fiscal Stability Treaty (FST), designed to reinforce the budget discipline of Eurozone governments, and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), an organization providing financial assistance programs to Eurozone members in financial difficulty. Both the FST and ESM9While the ESM was established by an intergovernmental treaty, a special amendment to Article 136 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) was needed to authorize its establishment under EU law. Currently, Croatia, the Czech Republic, and the United Kingdom have not signed the FST, and the members of the ESM are the nineteen states that are part of the Eurozone. were established through intergovernmental treaties formally outside the existing EU legal framework and do not bind all EU member states.

It is easy to imagine how flexible integration tremendously complicates the institutional landscape of international cooperation in Europe.10The EU is of course only one of a number of significant institutions for international cooperation in Europe. It co-exists with the Council of Europe, the European Free Trade Association, the European Court of Human Rights, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, to name but the most important. The institutional tapestry in Europe—in any field from economic co-operation to security to human rights—is complex, thick, and hard to penetrate. A host of independent but intertwined organizations and treaties with significant, if partial, overlap in membership looks like a nightmare to the rational mind of any external observer. At the same time, flexible integration has allowed for European cooperation to progress, even if in a messy and piecemeal fashion. The choice has rarely been between simple and messy integration, but rather between messy integration and no integration at all.

Ultimately, historical legacies and the need for compromises and flexibility provide rationale as to why the EU is so complex. Does this mean that there is nothing that can be done to simplify it? Is the EU really the least complex institution that could have been created to support integration and cooperation between twenty-eight sovereign states, each with their own historical legacies, economic interests, and geopolitical ties?

Can the European Union be made simpler?

Notwithstanding the benefits of complexity, there are significant downsides as well: it leads to legal uncertainty and regulatory fragmentation, it slows down decision-making, and it hampers policy enforcement. Most importantly, it makes the EU hard to know, appreciate, and trust. In light of these considerations, simplifying the EU’s institutional setup and regulatory output would be more than welcome. However, it would be extremely difficult to achieve in the current political environment. As argued below, simplification through informal institutional change or bureaucratic programs has only limited potential. Radical simplification designed to achieve a more straightforward institutional setup of the EU and a less fragmented regulatory environment requires reform of the existing treaties and renegotiation of the historical compromises embedded in the EU institutions. Neither the general public nor the political elites in Europe have the will or political capital to engage in treaty reform.

Informal simplification (early agreements and the ordinary legislative procedure)

A number of the EU’s institutions are so complex that even EU officials find ways to circumvent the strictures. The “ordinary legislative procedure” is a case in point. According to the formal rules of this procedure (previously known as “co-decision”), proposals for new EU legislation are made by the European Commission and then negotiated between the Council of Ministers and the EP during up to three readings. In between these readings, the draft proposal is handed back and forth between the three institutions for amendments. It would typically take more than two-and-a-half years for a proposal to move through the three readings before reaching a compromise at the end of the legislative process. To shortcut this rather lengthy and cumbersome procedure, EU officials have decided to reach informal agreements through direct negotiations between representatives of the three institutions (“trilogues”) during the first stage of the process, before the end of the first official reading. If the representatives can find a compromise text at this stage, the Council and the EP would adopt the proposal at first reading in a so-called “early agreement.” This is simpler and saves time. The use of “early” first-reading agreements has grown tremendously over the last decade, so that now they account for the majority of all legislative acts adopted under the ordinary legislative procedure.11For details on the rise of early agreements in the EU, see the post by Edoardo Bressanelli, Christel Koop, and Christine Reh on the EUROPP blog, http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/02/10/the-growth-of-informal-eu-decision-making-has-empowered-centrist-parties/.

Although attractive in some cases, such a pragmatic informal de facto simplification of the complex formal rules generates important normative concerns. First, it leads to a “decoupling” between the formal rules and informal practices, with negative consequences for the legitimacy of the former and the transparency of the latter. Second, in practice, the informal rules, if they stick, are soon codified in a number of inter-institutional agreements and internal rules of procedure, which in their totality might lead to even more complexity. Consequently, informal simplification cannot be a general solution.

Bureaucratic simplification (the Better Regulation program)

The EU actually has a special program that aims to achieve regulatory simplification under the heading of Better Regulation. Better Regulation is currently one of the ten priorities of the European Commission,12Details about the priorities of the European Commission are available here: https://ec.europa.eu/priorities/index_en. Better Regulation is listed under Democratic Change. and the initiative received strong backing from the First Vice President of the European Commission, Frans Timmermans.13See for example the press release of the European Commission from 19 May 2015 “Better Regulation Agenda: Enhancing transparency and scrutiny for better EU law-making,” available here: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-4988_en.htm. The program has worthy goals, such as improving the preparation of EU legislation, strengthening consultation with citizens and stakeholders, and ensuring the quality of legislation through impact assessment and evaluation. An important part of the Better Regulation agenda is the so-called Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme (REFIT) that combines various initiatives for legislative simplification and regulatory burden reduction.

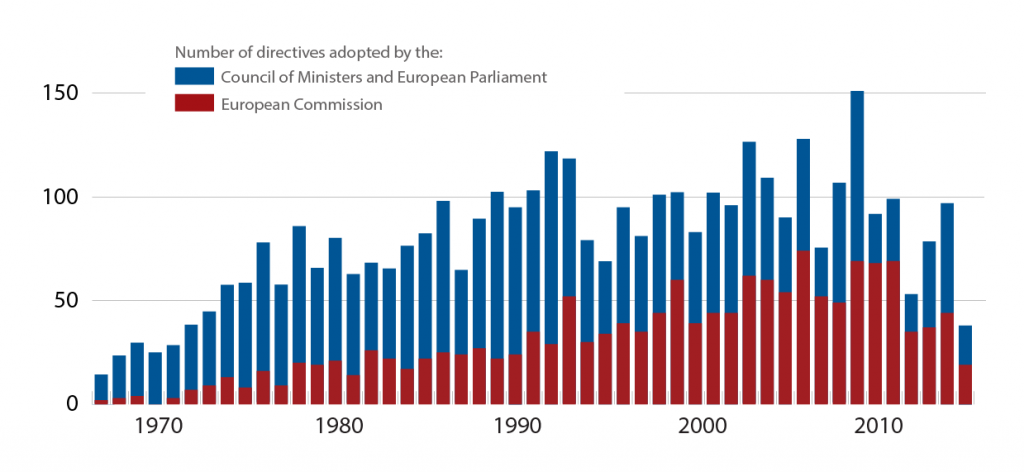

Figure 2. EU legislative production has been uneven over time

In practice, the track record of the Better Regulation program (which has been on the agenda since 2001), in particular the efforts to achieve legislative and regulatory simplification, has been mixed. The sheer number of EU directives adopted each year has decreased in the past decade (Figure 2), but it is hard to say to what extent this is an effect of the Better Regulation program and to what extent it reflects increasing disagreements and legislative gridlock in the EU institutions. At the same time, the volume and share of delegated legislation adopted by the European Commission14Delegated legislation is adopted by the European Commission under powers granted to it by the other institutions. It is similar to regulatory law adopted by the executive branch in the United States. has grown.

A few existing legislative acts have been repealed, but the number seems small compared to the administrative effort that has gone into identifying the rules that are no longer necessary.15For example, in the Staff Working Document from May 19, 2015 “Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme (REFIT): State of Play and Outlook” (available at http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/better_regulation/documents/swd_2015_110_en.pdf), the Commission mentions that two measures have been repealed since 2012 (p.3). In another communication from September 14, 2016, a figure of thirty-two repealed laws is provided (p.3) (Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council ‘Better Regulation: Delivering better results for a stronger Union’, available at http://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/better-regulation-delivering-better-results-stronger-union_sept_2016_en.pdf). Consultations, impact assessments, and policy evaluations are of course valuable, but they generate a significant administrative burden for the national and EU public administrations as well. Skeptics have argued that Better Regulation has been no more than window dressing for corporate-friendly deregulation.16See for example the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) Special Report authored by Andrea Renda, available here: https://www.ceps.eu/system/files/SR108AR_BetterRegulation.pdf.

It is hard to be against “better” regulation, but the host of well-intentioned initiatives under the Better Regulation program seem to have achieved, at best, marginal improvements. Furthermore, it is hard to sustain political attention and commitment to these kinds of administrative reform agendas.

Radical simplification through treaty reform

Any significant simplification of the current institutional setup of the EU would require a change of the EU treaties. All member states have to ratify new treaties or significant amendments to the current ones in force. In some countries, this might require popular referenda and the consent of national legislatures. This would be extremely difficult, if not downright impossible, in the current political environment in Europe. Proposals for treaty change would be used by Eurosceptic parties to incite and mobilize popular opposition toward the EU, regardless of the proposed treaty amendments. Even formally pro-EU political parties are unenthusiastic about raising the political salience of European integration that inevitably comes with treaty reform, in light of internal party divisions on the issue and increasingly Eurosceptic electorates.17See the recent article by Johan Hellström and Magnus Blomgren “Party debate over Europe in national election campaigns: Electoral disunity and party cohesion,” published in the European Journal of Political Research (2015, vol. 55, issue 2, pp.265-282).

The most ambitious effort to simplify the EU, the ill-fated proposal for a European Constitution, failed rather miserably.18In the history of European integration, there are also examples of successful simplification through treaty reform, such as merging the three sets of institutions of the three original European Communities into one set (1967) and merging the European Communities into a single European Union (starting in 1993 but still incomplete as the European Atomic Energy Community exists as a distinct organization). The proposal was drafted over a period of three years, signed by all heads of states on October 29, 2004, and then defeated by popular referenda in France and The Netherlands in 2005. Among its other proposals, the European Constitution would have radically shortened the existing EU treaties, replacing them with a much more concise document. It would have further simplified the decision-making and law enforcement procedures, and clarified the symbolic identity of the EU. For better or worse, the European Constitution never came to be, although it is unknown to what extent the proposed simplifications had anything to do with its demise.

. . . EU treaty reform is politically toxic. . . Renegotiations give opposition parties an opportunity to bash the governments for not defending ‘national interests’ enough.

However, the political lesson of this episode has been clear—EU treaty reform is politically toxic. Opening up the treaties would give new life to old quarrels between the member states about issues such as relative voting power and the like. Renegotiations give opposition parties an opportunity to bash the governments for not defending “national interests” enough. Attempts at reform also provide citizens with a rare opportunity to punish runaway political elites and faceless Brussels bureaucrats by rejecting the result of their negotiations.

In principle, simplification could come from streamlining the EU’s procedures and institutions. The requirements for legislative supermajorities could be slashed. The number of representatives involved in institutions could be decreased, by doing away with the rule that each member state is entitled to a commissioner, for example. The complex procedures that control how the Commission adopts delegated legislation (the so-called “comitology”) could be demolished. Yet, in practice, these are precisely the type of reforms that are most likely to invite opposition and resentment in the member states, both from the people and from parties playing on populist and nationalist sentiments. Proposals to decrease the powers of nation states at the expense of supra-national institutions and to change the relative balance of power between the nation-states are doomed to fail from the start. The proposal for a European Constitution, mentioned above, serves as a case in point.

Theoretically, simplification is also possible within a system of inclusive and accommodating institutions. For example, there could be a straightforward legislative process subject to supermajorities, but without any accompanying complex procedures for finding compromises. Or, there could be a treaty that forbids flexible cooperation arrangements between subsets of the EU member states. That would make for a simple system that only adopts collective decisions based on the logic of the lowest common denominator. With this configuration, one could imagine an institutionally simpler EU in which a wide range of opinions and interests are consulted, and integration moves forward only if nobody objects. But, even if such reforms leading the EU toward simplification were politically feasible—they would still require treaty changes—it is unclear whether they would be desirable to member states.

All political systems are complex, but the EU is special

Is there no way to make the EU radically simpler? Possibly not, at least not in the sense of establishing a more straightforward institutional setup. In the long run, the strictures preventing simplification may present an existential challenge to the EU.

All political systems are complex and messy. For example, the rules for legislative conciliation between the two chambers of the German legislature are not necessarily any simpler than the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure. The reality of filibusters in the US Congress is no easier to explain than the consensus culture in the EU’s Council of Ministers. The rise of delegated legislation made by the executive branch is no less worrying in the United Kingdom than it is in the EU. However, the EU is different.

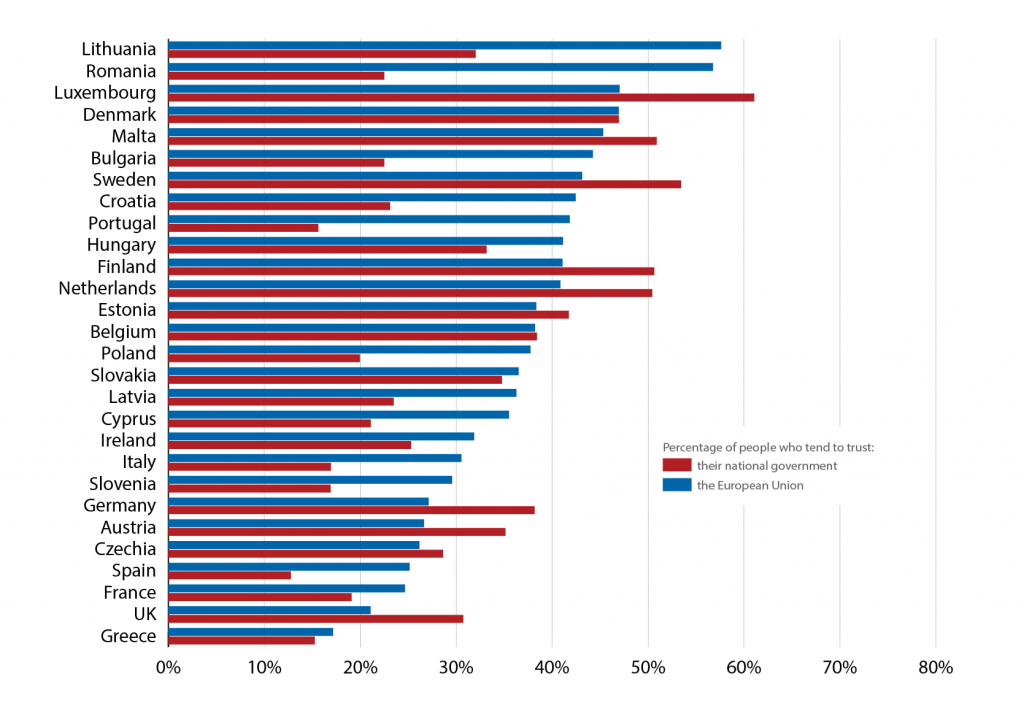

Figure 3. Public trust in the EU and in the national government

The EU is a polity in the making. The legitimacy of the British, German, and US institutions in the eyes of their citizens can be taken for granted, to a considerable extent, but this is not the case for the EU. Precisely because the EU is a relatively young and unsettled political system that still has to gain broad popular acceptance of its institutions, it would help if it were simple and straightforward to explain to European citizens. As argued above, it is not, and this is not likely to change any time soon.

What can be done?

“Simple” means easy to understand and uncomplicated in design, but it also means an institution that is humble and transparent. If the EU cannot become more straightforward, it could still become humbler, in the sense of being more modest about its own importance, and transparent. This, in the long term, could go a long way toward winning the trust of European citizens. Currently, trust in the EU is rather low, although highly variable across member states and not necessarily lower than trust in the national governments (Figure 3). General lack of knowledge about how the EU works is one of the many factors contributing to this relative lack of trust.19Approximately 47 percent of the citizens who consider themselves knowledgeable about how the EU works tend to trust it, while only 27 percent of those who do not consider themselves knowledgeable about the EU do. Similarly, while 44 percent of the citizens who correctly answer all three simple factual questions about the EU tend to trust it, only 20 percent of those who answer all questions incorrectly do. These comparisons are based on data from the 2013 edition of Eurobarometer survey (Eurobarometer 80.1, 2013). The strong association between knowledge and trust is possibly confounded to some extent by the level of general education and socio-economic status, and the causal links between these two phenomena likely work in both directions (e.g. people who do not trust the EU are also less likely to learn anything about it). But the associations remain strongly suggestive of the positive impact of subjective and objective knowledge about the EU on trust in it.

Only citizens who trust the EU institutions to a sufficient degree will allow them to lead the policy initiatives that can support economic growth across the continent and respond to global challenges with the required speed and determination. Gone are the days when the European elites could move European integration forward while the public watched from the sidelines, largely uninterested but broadly supportive. Now that the “sleeping giant” of public opinion has awoken, the trust and support of the people need to be actively won in order to give the EU and the national governments the legitimacy to enact the reforms that would make the EU economies stronger and its societies more resilient. There is no silver bullet solution to achieve this, but several recommendations can be made that would help.

First, the EU should aim to simplify the message it projects about its own identity. Currently, there exists a significant gap between the enormous importance of the EU, as asserted by national and European politicians, and ordinary Europeans’ scarce knowledge about the institutions. If citizens believe the claims that the EU is important, but they do not understand how it works, they will not trust it. In fact, the EU is not quite as important in many of the areas that people strongly care about: internal and external security, welfare, and social protection. The EU is, of course, important when it comes to the regulation of the internal market and other areas, but these do not necessarily require the same type of popular legitimacy as military defense or redistribution policies. If politicians scale down their claims about the importance of the EU, and instead focus on the issues that mean the most to the people, citizens might learn to trust the EU.

Second, all EU citizens, and young Europeans in particular, should have the opportunity to learn more about the EU and European integration. At the moment, most high school students across the EU finish secondary education without exposure to any information about the EU. It is hard to expect that people would understand, trust, and support the EU if they have received no reliable information about its function and significance during their formative years in school. The EU is complex, but its basic institutions and procedures are not beyond comprehension. A bit of systematic knowledge provided to all students in the EU can go a long way toward building trust and understanding between citizens and the EU institutions.

Third, the EU should be clearer about the fundamental values for which it stands, and more consistent in the promotion of these values with its policies and actions. This is not always easy. In its external relations, for example, the EU must constantly balance between promoting its core values and protecting its economic and security interests. Yet there is no greater hindrance to garnering public support from European citizens than to see the EU compromise its core values, for example, by putting up with violations of press freedoms within its borders or making deals with despots to serve its short-term interests.20Consider, for example, the EU negotiations for a “refugee deal” with Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi in 2010. Gaddafi initially demanded 5 billion euros a year to block the arrival of illegal immigrants from Africa. A few months later, the European Commission and Libyan officials agreed on increased financial support for Libya’s reforms amounting to a total of € 60 million for the period 2011-2013. See European Commission press release database at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-10-472_en.htm?locale=en

Fourth, the EU should be more transparent. This is an often-acknowledged point,21For example, it is part of the recent “Trade for All” initiative, which aims to achieve a more responsible trade and investment policy. but somehow progress toward this objective remains slow. Unlike the United States, the EU still does not have a mandatory, publicly accessible register of lobbyists.22See the reactions to a public consultation on the proposal for a mandatory EU Transparency Register at http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/civil_society/public_consultation_en.htm. The Council of Ministers still does not systematically publicize information about the positions of different member states during legislative negotiations. The European Commission still does not reveal how and why it decides to settle suspected cases of EU law infringements by the member states. Transparency about the actual conflicts that shape policy making and implementation in the EU might present a more confrontational picture of the EU at first, but in the long term it will make clearer to people the nature of policy debates at the EU level, and how the EU institutions work to solve them.

Fifth, the EU should focus its regulatory attention only where common European rules bring real added value for all citizens, then make sure that these rules are effectively implemented, and have a positive impact. As explained above, there is a trade-off between the flexibility of rules and the chances that they are approved by the member states. Perhaps in many cases it is not worth having rules so riddled with exceptions and national discretion that they have no real impact on the ground, but merely generate a great deal of bureaucratic activities around them. Perhaps the EU should do away with directives as a type of legal act entirely, focusing instead on directly applicable regulations, and streamline enforcement so that member states cannot drag their feet in implementing the EU rules for so long.

It is hard to achieve all this within the framework of existing treaties, lack of political commitment to Europe by national politicians, and skeptical publics. However, for the sake of Europe’s future, it is worth trying. An integrated Europe that citizens do not trust or understand is not viable in the long run. A political system that is complex but does not deliver effective policy solutions is a political system in peril.