Read the highlights

Event transcript

A conversation with

Prime Minister Carl Bildt

Former Prime Minister, Kingdom of Sweden

Stephen Hadley

Executive Vice Chair, Atlantic Council

Former National Security Advisor to the President of the United States

Secretary Ernest Moniz

President and CEO, Energy Futures Initiative

Former US Secretary of Energy

Minister Ana Palacio

Former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Spain

Lord George Robertson

Member, International Advisory Board, Atlantic Council;

Former Secretary General, NATO

Moderated by

Frederick Kempe

President and CEO, Atlantic Council

FREDERICK KEMPE: It is terrific that we’ve got this lineup of experts and—to do some fast thinking about what they just heard and then put it into context.

I’m going to start. The Atlantic Council is about working together with friends and allies to shape the future, and so you’re going to hear that with a British, a Swedish, and a Spanish colleague. And I’m going to start with our international partners and then go to our American friends.

And maybe I’ll start with you, Ana Palacio, former foreign minister of Spain and member of the Atlantic Council Board. What did you hear in that that is meaningful to you, and then meaningful to Europe and to Spaniards?

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: Well, I think it’s meaningful to all of us because it was a domestic speech, but the speech of the city on a hill, there is light in the—in the hill. And in the end it spoke about unity, about truth, about civic responsibility, and this is our common challenge for all democracies all over the world. So it was a speech for all of us in this idea that United States has to lead by example.

And again, this idea of exemplarity, we need it. We need it badly. We need it from Europe.

But as I say, for me it was a very domestic speech that was extremely universal for all of us that believe in democracy, that fight for democracy, and that have this idea of a shining city on a hill about the United States. It’s back. It’s not America back; it’s this America that is back.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you for that, Ana.

And for those who are listening in, you can pose questions through the app, the Atlantic Council Global Energy Forum app, which I know most of you have. For those of you who would rather do it over Twitter, you can send it to my own Twitter feed at @FredKempe and we’ll get your questions, and then say to whom you—who you are and to whom you’d like to pose your question.

Just a real quick follow up on that, Ana, and then we’ll move on, is: What are you going to look for in the first days, the first weeks of the Biden administration? What is going to be most important for you to see?

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: Well, honestly, signs that America is healing itself. I think that this is the message. And by the way, it was truth—I mean, it was—it rang genuine when he says with emotion that they will remember us as the heal broken land. This is what is important. This—because without healing, America cannot lead. And America needs to lead in order to lead—needs to heal—excuse me. Needs to heal in order to lead.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you for that, Ana.

And let me pass next to Lord Robertson. Where are you sitting? Are you in London or are you in Scottish climes?

LORD GEORGE ROBERTSON: I’m in Scotland. England is underwater with floods and tonight Scotland is going to be under two or three feet of snow. So that’s where I am, watching what’s happening in America.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Well, as former NATO secretary general, but also the former—an existing politician in the UK, you know a lot about domestic divisions. But you also know a lot about international challenges of alliances. Tell me how you consumed this inaugural speech and what you were hearing.

LORD GEORGE ROBERTSON: Well, I said to myself: Glory be, America is back. American leadership is back. You know, for four years even the critics of America felt the vacuum that had been created by the fact that America was not exercising the leadership that the world at the moment needs. There are so many problems facing the world—whether it’s migration and climate change, international terrorism, the competing between great powers—all of that needs American leadership. And having known Joe Biden for ages, you know, I just was so comforted today that although he was addressing a domestic audience, with some domestic messages, the fact is that the world was listening. The world was wanting American leadership.

And I think the world was reassured that America was now going to rebuild alliances that had been damaged. It’s going to recreate relationships so important in the world and so important for America’s own security and safety. And I think that was the message that came out of it. I wrote down a phrase from Amanda Gorman, the young woman poet who spoke where she talked about America being bruised but whole. And I think, you know, that is a message that I think will resonate beyond America’s shores.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you for that. And then just quickly, on the NATO front, you know, there was a lot of handwringing, “NATO’s going to be destroyed by President Trump.” Well, none of that came to pass. In some ways, in terms of troops in Europe and troops particularly forward based in Eastern Europe, some would say it’s even stronger. What are you going to be looking for from President Biden as former NATO secretary general?

LORD GEORGE ROBERTSON: Well, I want—I want President Biden to reassure allies that America is still the principal leader within NATO, it’s still robust, still believing that alliances are the best form of defense for the United States of America and making that message clear. But I also expect, and indeed I want him, to tell the Europeans and NATO that they’re going to have to do much more for themselves. They’re going to have to do much more in the interest of the whole alliance, and that they cannot simply ride along on the coattails of American expenditure. I think they got a fright during the Trump administration. They’re spending more. But they need to be told that America has got other priorities in the world and that they therefore have to do much more to help America, but also to help themselves.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you, Lord Robertson, also a member of our International Advisory Board.

Now turning to another member of our International Advisory Board, Carl Bildt. Former prime minister of Sweden, foreign minister of Sweden. You know, with what sort of ear were you hearing this inaugural speech? What did you hear? And what are you looking for going forward?

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: Well, I think it was a rather unique inaugural speech, in that the focus was almost—it was uniquely domestic. It was healing the nation, repairing the rifts in the fabric of American politics. I mean, he had a phrase here, he said: “end this uncivil war.” Another way of saying that the United States is [at] uncivil war. And his number-one priority—one, two, three, which is necessary also from the point of view of the outside world, is to repair that. And that’s not going to be entirely—it was a good speech. It was a good start. But I think everyone who follows the political affairs of the US knows that it’s an uphill battle and a lot needs to be done.

The world was fairly absent. I mean, I think he had two passing references to the climate challenge and he mentioned a need to repair relationship with allies. But otherwise, if you were to prepare—or compare these speeches over the decades, I think this was probably the one that was the most focused on solely domestic affairs and healing the nation, which is understandable, necessary, and also a precondition for America taking a stronger role in the world.

FREDERICK KEMPE: And it’s very interesting, not only was President Trump not mentioned any time in the speech—

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: No, but he was—

FREDERICK KEMPE: —neither was China, neither was Russia, neither was NATO. There wasn’t any of that. And so—

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: No, but it was—it was—Fred, it was an anti-Trump speech, every single sentence, without mentioning the name.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Exactly. But in terms of—and then I’m going to turn to our two American speakers—but in the opening months, maybe one hundred days, six months of this administration, what is the international issue you want to watch most? What is—what is most important from a European and from your Swedish point of view?

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: Well, I think, first, he’s going to reach out to allies and, you know, sort of symbolically say we think that you’re important and initiate a dialogue on different issues. Then the climate issues are imperative. We have the COP26 coming up in Glasgow in November. That’s practically tomorrow. We have all of the vaccine and the vaccine nationalist issues that need to be addressed. We are not safe from this pandemic until all of the world is safe. And then I think there is a slight urgency to sorting out how to handle JCPOA in order to prevent a new crisis in that part of the world.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you so much.

So President Biden plans to sign fifteen executive orders today, the—undoing the Muslim travel ban; you know, the Paris Climate Agreement, coming back into it; national mask mandate; and others. Let me turn to—let me turn to Secretary Moniz. And so Prime Minister Bildt, Minister Palacio, Lord Robertson, thank you so much for this.

Secretary Moniz, can you give us what you heard? Everyone listens to this speech with a different set of ears. You’ve, obviously, served—you’ve served in the Obama administration. How would you compare this to Obama inaugural speeches? And what did you hear in this that resonates with you?

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: Well, Fred, first of all, I certainly endorse what our colleagues have said about this being a domestically focused speech of international implications. But I’d like to just add that it is comforting to hear our colleagues from Europe and the UK talk about restoration of American leadership, and that will obviously require some blocking and tackling like restoring alliances, restoring trade relationships, restoring international financial institutions, and the like.

But I guess I’m going to add a qualifier to their statements, and that is that while I think President Biden is almost the ideal person for this rebuilding task—his longstanding relationships and skill at coalition-building will be very important—but I guess I’d like to hear perhaps more from our international colleagues about whether they really believe there will be full trust in the United States until, frankly, we’ve gone through at least one or two more presidential election cycles, frankly, in which the normalcy of our politics can be—can be reinforced. So I think that’s very important.

Secondly, in terms of the executive orders that you mentioned, Fred, the comity will immediately be challenged by some of those, for example the immigration—the immigration statements, et cetera. You know, I think of the—of the president as having a critical role as the chief risk officer to ameliorate catastrophic risk to Americans and to our global partners. And I think—you know, I would list among those catastrophic risks climate; the pandemic, clearly; cyber; a variety of nuclear issues, including, as was mentioned by Carl, Iran—North Korea should be in there as well. And I think on some of those I’m optimistic about more—a more bipartisan approach, like on the pandemic, like on cyber. I’m not optimistic about that being—that bipartisanship being easily won in the nuclear arena, those cases that I just mentioned.

And on climate, I think it’ll be a mixed bag in terms of bipartisanship. For example, we’ve seen even in these four years the innovation agenda for clean energy has actually garnered quite strong bipartisan support, and I think that’s a door ready to be swung open even wider. Whereas when it comes to comprehensive climate policy, where even with a Democratic majority in the Senate—the very slim majority—it’s going to be difficult to get coherent policy.

So I think that’s—those are some of the challenges now that I see that will hopefully be helped by his unifying message, but are going to be challenged as soon as we start getting into some of these policy specifics. And as he said, it would be wonderful if we could have civil discussions about those differences of policy.

FREDERICK KEMPE: One quick question for you before I turn to Steve Hadley. And then also among this group, as we get going, please intervene on each other. Let’s make this a live discussion. I’ll also throw in questions from others so you can respond to what others have said. But so much of—it wasn’t much discussed in the speech, but so much of what has been planned for the administration places clean energy, climate action, as well as international cooperation on all of this at the heart of a post-pandemic future. What do you think in concrete terms you’re going to see earliest, most different from a Biden administration? Obviously, Secretary Kerry, who you served with, is going to be the climate czar, so to speak.

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: Well, John Kerry’s appointment as the international envoy clearly was a major signal, including his Cabinet-level appointment, et cetera. But in terms of the czardom, we have to remember that there’s also a major contingent in the White House: Gina McCarthy and Brian Deese and many others. So I think, for one thing—and I think this is where remote working challenges things more than the opportunity to really sit together routinely—it’s going to require real teamwork on this group of John Kerry, the White House, but also to remember that almost every Cabinet appointment across the government has been emphasized as one that will reinforce climate—for example, Janet Yellen at Treasury being a major advocate for charging for carbon emissions.

So I think today we will have executive actions that roll back some of the Trump rollbacks on efficiency standards and methane emissions and the like. We will also have new ground, like emphasizing a social cost of carbon in cost-benefit analyses, like having corporate risk disclosures for climate become paramount. The Gary Gensler appointment at the SEC highlights that. But again, when it comes to getting nationwide climate policy, this is going to be a real coalition-building exercise and a tough one, because I don’t think we are there yet in a—in a bipartisan way.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you so much.

So, Steve, national security adviser. You’ve been through transitions. You heard the inaugural. What are your own takeaways from what you’ve experienced today?

STEPHEN HADLEY: Well, I thought it was a terrific inaugural address. I thought the president said exactly what needed to be said.

You know, I think the country’s had a bit of a crisis of confidence. It’s been a tough four years. January 6 and the disruption in the Capitol really, I think, shook the country. And I think what the president set for himself was to reassure Americans that we can have faith in our democratic principles, in our democratic institutions. We can have faith in our values and that if we pull together and are true to those values, as he said, there’s no problem we cannot solve.

Now, I suppose some people will say that’s rather hyperbolic. But I think the essence of what he was trying to say—and he’s right about it—was he made—he had a phrase that democracy is fragile but resilient. And we saw the fragility of democracy with the challenges to our most recent election, culminating in the demonstrations January 6 at the Capitol. I think the story that people are beginning to write is the resilience of our democracy, that in the midst of a pandemic when rules of how to vote had been radically changed—(laughs)—the American people figured out how to cast their votes.

We had the highest turnout since 1900—120 years. And it was a free and fair election. And we saw in all the challenges people at local levels, local state attorney generals, a lot of them young, a lot of them women, running a terrific—what turned out to be a very free and fair election. And then resisting both legal challenges—which were rejected by Republican judges, Democratic judges, some judges even appointed by President Trump—and then the political pressures. And we stood up—they stood up to those. The institutions worked. The electoral structure worked. We have a new president.

And I think, again, he captured it right. It’s fragile, but it’s resilient. And I think in some sense what the president wanted to do was to rally the American people behind those institutions, behind our democratic principles and say: We can succeed against the challenges we’ve got. And I think he accomplished that. Yes, it’s only one speech. Yes, we’re going to have to see what he does. But tone is important. And I think he set the right tone, and I think he had the right message for the American people.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So a follow up for you, Steve, and then I’ll watch in front of me all of you to see when you want to jump in, and I’ll throw in some questions as well. One question that I got is: I know Jake Sullivan’s the new national security advisor. Work starts, I assume, right away. How does—how are the first hours conducted in a new presidency? Obviously, this is a little bit different because vice—or, President Biden has been Vice President Biden, so he’s been through a lot of this before. But what are the—what are the crucial issues?

And then maybe a second, related—thinly related question. You just talked about the resilience of our institutions, democracy. That speech would suggest that our international obligations at the moment either have to take a little bit of a backseat to what we need to get done domestically or are one and the same. And I’d love to have you talk about that.

By the way, for those of you listening in, Steve Hadley is not only former national security advisor, he’s the executive vice chair of the Atlantic Council Board. So he is responsible from the board position of helping us think through strategy, both for the institution and how we want to address strategic issues as an Atlantic Council in terms of the global picture.

STEPHEN HADLEY: I thought Ana Palacio had it right. While it was, as Carl Bildt said, it was a speech directed at a domestic audience, the content of it was really a message, I think, for democratic-loving people around the world. And you know, America will not be successful leading in partnership with our friends and allies in the world if we do not have a firm foundation at home—economically and politically.

So in some sense I think it was a message to our foreign partners and friends and allies that America is emphasizing and returning to those democratic principles which we’ve stood for in the world and which have been such an important part of our leadership. So I would say while the message was domestically focused, it actually was one that was sending a very strong message to the world that, as President Biden said, America wants not to be an example of power but to show the power of its example. And I think that message is going to be well received.

In terms of what they’re starting to do now, every new president comes in, increasingly there is a list of executive orders which kind of clears some of the debris. But one of the things that the chief of staff, and the national security advisor, and the folks have been doing, I’m sure, is scripting what the first day of the president’s life is going to be, what the first week is going to be, what the first month is going to be, and then what are the first one hundred days. And there’s a lot of talk in those opening days about what does—what does the president want to do, what do the American people need to see the president doing, and what does the international community need to see. Who does the president call, in what order, and what is the message.

So there’s a lot of scripting that goes on to get the new president launched, and I think that’s probably what you’re going to see unfolding in the next day and week or two ahead.

FREDERICK KEMPE: OK.

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: Fred, may I jump in?

FREDERICK KEMPE: Go ahead, Ana.

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: You asked me what do we expect from the United States, and I said signs that the United States is healing because without healing United States cannot lead. But the other aspect that we expect is signals that the leadership of the United States has changed, that it is really an inclusive leadership.

I mean, I don’t have and I think none of us from the other side of the pond have to prove our Atlanticist credentials. Nevertheless, honestly, when you have been in office with an American administration, many times you took for granted your allies. What I think that is, is this new inclusive leadership is really—there’s leadership, because the leadership, I think we understand that it has to be America. And I hope that—I don’t want to touch upon this because Carl Bildt wrote a fantastic piece at the Project Syndicate explaining the mistrust that there is, and not just in Europe.

So I won’t touch on this. But I think that we expect twenty-first-century leadership of the United States that has to be inclusive. It’s not a hegemonic leadership, taking your allies for granted. It has to be different. And I think that the message of this—of this first speech, and I hope that it will be followed by executive orders, by moves that will prove that this America that just will lead by example, but will lead by example in an inclusive way.

STEPHEN HADLEY: Fred, if I could just add—

MR. KEMPE: Please.

STEPHEN HADLEY: —a foot stop on what Ana said, I think it’s very important. I’ve talked to people about how America has to lead in a different way because the context has now changed, not just the last four years but more broadly. And so when we talk about—Americans tend to talk about American leadership and return to leadership.

For some people, that sounds like the soft hegemony of American power, and I would like to see our leaders talk more about engagement and partnership and inclusion, as Ana did, so that it recognizes we want to lead in a very inclusive way where we’re going to listen to our partners as we come together with our own policies so that we can work these issues together because, in some sense, the issues are sufficiently daunting and the agenda is so robust and the challenges are so great that if we cannot find a way to do it together, the United States with our friends and allies, we’re not going to succeed. It’s as simple as that.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thanks—thanks, Steve, for that point.

LORD GEORGE ROBERTSON: Strongly—can I just strongly agree with what Steve has just said? Because, you know, the president went on about democracy today and there is a crisis of democracy in the world, you know, not just in the United States. I heard Megyn Kelly last night being interviewed on British television, you know, and say, can he unite the country, and she said no, not easily, I mean, because Trump was a symptom, not the cause, of the problem of the division inside the United States.

But across the world the rise of authoritarianism is something that bothers me and should bother a lot of people as well. So America has got to lead by example but it’s got to do it in a muscular sense as well. We’re going to have to establish those democratic principles of the rule of law and the separation of church and state and private property and mixed economy. These are things that are now, I fear, going out of fashion, but which he’s going to have to take a lead on. And I think he articulated that today, and I think it resonates in the world community as well.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So let me turn next to—I’m going to—for simplicity’s sake, I’m going to go with first names here. But let me turn to Ernie and then I have a question for the international group and a question for the American group.

But Ernie?

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: No, I just wanted to comment that I strongly agree with the three perspectives we just heard. But I do want to add, to be explicit, frankly, the issue of taking allies for granted also has the flip side in the past of allies taking the United States for granted—

FREDERICK KEMPE: Right.

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: —and so I think we really do have a joint effort called for in that context and, certainly, in the context that George just referred to in terms of the challenges to democracy, unfortunately, throughout the democratic world.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you for that. So for Carl, Ana, and George, and this is related questions on your view of the United States, how deep is distrust right now for the United States is essentially the question, and Ernie pointed to this as well, and what is it going to take.

Is it going to take a couple of presidencies or can this inauguration and six months do a lot of good, or have things shifted among our partners and allies? And I wonder if—the second part of this is what impact, because there’s going to be a lot of emphasis in the Biden administration of social justice and equity, does that have an impact internationally in how you look at the United States as a partner or a leader?

So why don’t I start with you, Carl, and then go to Ana and George, and then I’ll come back to Steve and Ernie with a question for our Americans.

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: Well, things have shifted. As Steve indicated, it’s a different world today, so it requires a different way of handling that, certainly from the US side, also from the European side. No question about that. But I think the conditions for doing that are much better now.

I mean, the big shift, if I see it from the European side, is that we’ll have a perfectly normal person in the White House that you can have perfectly normal conversations with, and even if our focus now is on Joe Biden as president, we should not forget that he has an extremely experienced, well known, good foreign policy team that one can connect with.

Then the question—I wouldn’t say mistrust, but I would definitely say nervousness. Europe is nervous. Europe is nervous when they see an America in crisis. I mean, to take the Joe Biden phrase “uncivil war,” January 6 was a shock to Europeans. We trust the relationship across the Atlantic. We are dependent upon it, perhaps over dependent on it, as was pointed out, and when this America is in such a profound crisis we get nervous.

And there was also the reflection on, of course, the election result. I mean, Donald Trump had a very impressive election result. No question about that. He had the highest result for any sitting president, I understand. Joe Biden was, of course, even more. But it’s not over until it’s over, and you can see in the European media and debate discussion whether—when history is written, is it going to be Trump or Biden that is the parenthesis in the long run. And, of course, that introduces an element of nervousness at the same time as there is a sort of an intense hope that the president succeeds, that the healing works, and that we can work together constructively on all of the issues.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you.

Ana, do you agree with that?

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. And again, just pointing to something that Ernest Moniz said, I think that the negotiation of the Paris Agreement is just an example of inclusiveness. And he played—I mean, Ernest played a key role, and this is the kind of expectation that Europeans have. And it was not easy. We wanted a legally binding instrument, and we were convinced by—I mean, in great part by your team and by you yourself.

Having said that, you know what, Ernest? The leadership entails some other responsibilities. So you are absolutely right. And I think that we Europeans—and George Robertson said it—in NATO, we have to take our part of the burden and we have to be there, and we have to make the balance. Our speech about strategic autonomy, which is now one of these buzz expressions that circulate in Brussels, each one puts in it what—the wishes or the non-wishes. Nobody knows exactly what this means and nobody wants to have it defined, but it’s a fantastic buzzword. But we need to be realistic about this strategic autonomy, realistic in delivering on the one hand side and then on our dependence in security terms.

And our goal to the United States, you have mentioned the COVID. This morning, Ursula von der Leyen, so the secretary of the Commission, went to the European Parliament and made a speech about the inauguration, which is—you know, it’s kind of exceptional. We have a communication on bilateral relations from December, but she went there and she insisted on this idea of having the government of the United States participating in the COVAX, which is this—precisely this—I mean, this initiative, and highlighting—because I think that we also have to highlight all what United States is doing and has been doing beyond the Trump administration. And she was highlighting private actors and other actors, and we—one of the things that we learned during the Trump years is that there was much more about the United States internationally than the White House; that there were states and governors and private people and companies and mayors and a bunch of people—judges—that were there.

So, again, I—you are right. We need to clarify ourselves, and this is—I mean, this is our challenge. Of course, I always say that we have gone a long way—a long way. And in some issues, for instance in Brexit, we proved that we can stand together when we think that this is systemic, existential. I think that now the European Union has to get a realistic, systemic, existential dialogue with the United States that will encompass COVID, will encompass of course climate change, because for us climate change is in our hearts. We consider that we are the standard bearers of the climate change initiative, and we need to establish—but not just on climate change; on technologies. And I think that one issue which is—it’s not strategy, it’s tactics, but it’s important—is to establish concrete channels.

We have this bilateral council on energy. We need to have something similar on technologies, on COVID, on all the challenges that we are pointed.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you, Ana.

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: Last but not least, just one sentence on the justice. I think that for us Europeans, you know, there are things that—there are people without health insurance or without health. This is something that we cannot understand, as simple as that. So, yes, we very much welcome that there are signs there that you go a bit European. Don’t go European in other areas, but on this one, yes. (Laughter.)

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you, Ana.

So President Biden’s departing right now to Arlington Cemetery to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier with his—with the first lady.

George, just very quickly, on the issue that came up, but particularly in relation to the US as a trusted and reliable ally, has that—to what degree has that suffered? And what does it take—or not? And what—you know, how—what impact does this inauguration have on the first weeks/months of the Trump—or the Biden administration? Again, to the question from the—from the audience of can one just overnight say black is white and white is black, or is there going to be a real gray area for a long time?

LORD GEORGE ROBERTSON: Well, Carl was right when he said that the rest of the world is still nervous. People look at seventy-four million people voting for Donald Trump in this election. And that nervousness will continue because America is bitterly split.

But you know, we don’t really have any right to be judgmental. You know, these splits exist elsewhere. Populism is not confined to the United States. Look at Hungary. Look at—look at Poland. Look at what happened in my country with Brexit and our leaving the European Union. You know, these sentiments around that Joe Biden identified today in our societies. You know, when he talked about facts that are manipulated or even manufactured, I mean these are serious challenges that we, democratic politicians, have got to face up to. And it’s not just in the United States.

So there is a collective effort going to be required to build back the trust and the engagement that is going to be required. How do we face up to the challenge of China? Not just the trade issues that have polarized American and China at the moment, but the Belt and Road policy? The mischief-making by a resurgent Russia? You know, the assertion by people in the world against the world order? These are big challenges we’ll have to take place. But the recovery has started today because Biden has made it absolutely clear that America is back in the leadership chair.

FREDERICK KEMPE: And let me now turn to—thank you for that. And let me turn to—

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: Fred, could I just?

FREDERICK KEMPE: Go ahead.

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: OK, Fred, well, I just want to add on that point this question of the—because I raised earlier this issue of the process maybe taking a while to settle down. But I believe, and I think Steve would probably align with this statement that I think it’s going to be very difficult to truly rebuild the trust until we return to some greater degree of bipartisanship on international issues. Certainly if I were a non-American looking at America and seeing what’s happened, I would be very, very, very, very nervous in terms of committing without seeing an administration, congressional, Republic, Democratic improvement in communication and convergence towards some common positions.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Ernie, thank you for that.

Steve, that’s a good segue, and this will be for both of you, and that is: What foreign policy issues will President Biden have the toughest time on working across the aisle, and what will be the areas where he can find bipartisanship the fastest? Let me just leave it at that. I mean, we’ve seen some of the testimony yesterday from the new Secretary of State Tony Blinken on China. But I’ll come back to a follow-up question. But just let’s use that question. Where is he going to have the toughest time working across the aisle on foreign policy issues, and where can he find bipartisanship the fastest? Steve, why don’t we start with you?

STEPHEN HADLEY: So I think there’s a lot of consensus about the need to use friends and allies. I think there’s a lot of consensus that if you’re going to deal with China it is going to take the combined diplomatic and political influence—and, quite frankly, the combined GDPs—of the United States and friends and allies to have enough leverage to change—to have any chance of changing some of China’s behavior. So I think this working with allies, particularly on the issue of China, I think there’ll be a lot of resonance. I think there’s a lot of consensus on China policy. I think there will be some turning down of the rhetoric, probably some narrowing of the executive orders the Trump administration has issued. But I think there’s a lot of bipartisan consensus in the American public and in the Capitol Hill on China. So I think that will be a good one.

I think there—I think Iran is going to be one of the more divisive issues. And my worry is that the Biden administration will kind of put the needle down at where they were in 2016-2017, when they left office. And Ernie can speak to this, but I think there are problems in the agreement that were recognized. Ernie would say there’s some limitations to the agreement. Because it’s now six years after the agreement was put in place some of the limits are expiring. So the question of how you get back into the agreement is a question.

And I hope that the Biden administration would recognize that while the nuclear issue is important that—two things. One, our allies from the region need to be participants this time in the way they were not. And secondly, that at the same time we work the nuclear issue we have to also address what Iran is doing with its ballistic missiles and its regional area—and in the regional disruption. If I think the Biden administration takes that broader view, there’s a chance of bringing some Republicans along. But I think it’s going to be a real challenge to manage it. And I think Ernie’s going to have an important role.

A lot will depend on how the president does in his opening rounds with the Congress. I think he can get bipartisan support for more aggressive action against the coronavirus. I think he can get bipartisan support for an economic relief package to help the country get through the coronavirus. I would think there’s a good chance he can get bipartisan cooperation on an infrastructure bill, particularly digital infrastructure, particularly broadband for rural areas, things like that. And if he can deliver on those, I think it sends a message, to Ernie’s point, that there is—and to the world—that there is a possibility of Republican and Democratic cooperation.

In that respect, I put one footnote. I was a little surprised to hear that people are saying that President Biden is going to lead very quickly with an immigration reform package. And that is tricky. I mean, President Bush had an immigration reform. We thought we would get it. We did not. There was then the 2017, I think, effort—maybe I’ve got the date wrong—that Senator McCain was involved in. Maybe it was 2013. That failed. Immigration post-Trump is still a very divisive issue. And I think one of the things that the administration needs to do is really think about that. Their view may be that it has to be addressed and that their leverage is greatest having just come into office. But if—but if the president is defeated on immigration reform, I think that’s a real blow.

FREDERICK KEMPE: OK. Thank you for that, Stephen. Ernie obviously, not to address the entire issue, but you were so deeply involved in the negotiation of JCPOA. I’d particularly like to hear your response on that.

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: Yeah. I’ll come to that, Fred. Let me just make one point on what Steve just raised on the immigration, because I actually raised the issue of the executive order that I understand will come out today on path to citizenship. Just as a footnote, I believed there was a window where the immigration reform could have been successfully pursued. And that was in the 2009-2010 timeframe. The stars were kind of aligned briefly. But the president—President Obama—chose to make the health care issue the lead one. Another controversial issue. And I think that moment passed, shall we say, on the immigration. Whether it’s back, well, we’re going to find out soon.

I think on the original question, Fred, first—I’ll comment on Iran—but first to use as the example what’s been discussed about China, where clearly there are national security issues, there are trade issues, there are climate issues. And I think that—I agree with the statement that this is a place—and, Steve, with the combined GDP I strongly agree that we are not, frankly, using our market power collectively in terms of those discussions.

But that’s where, going back to what Ana said is troubling, to be perfectly honest, I’m not criticizing the action but the fact of Europe and China doing a trade deal just before Biden came in does not sound to me like optimum timing to have a joint strategy put together. So we got to get our act together collectively. And that includes in addition, of course, our Asian friends, Japan and Korea and the like. So we got some work to do. And it’s all of us in that—in that context.

Now, on Iran, I certainly agree with most of what Steve has said. And we’ll be comparing notes later. (Laughs.) But I think it’s very important to start not with a “Mother May I.” That is, I think there is no doubt the president has said: He is going to rejoin diplomacy on Iran. Not a mother may I, but really serious discussions first with both sides of the aisle and Congress, with our European allies, and with our Middle East allies. Again, it’s not mother may I. It’s how are we going to constructively go to a JCPOA+. And I think to do that the president and his team are going to have to be prepared right from the beginning to emphasize, yeah, we see JCPOA as a potential steppingstone towards JCPOA+.

But the question is, how are we going to maintain the leverage to make sure that negotiation is going to be seriously enjoined? I mean, I have my own ideas on that, but I think the main thing is we got to have a plan about leverage to go beyond JCPOA.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Yeah. I think that’s interesting. And the other—on the China issue, it’s interesting that Secretary Pompeo went out, with the State Department branding, what’s happening to the Uighurs is genocide. But then interesting that Tony Blinken in his confirmation hearings said, yes, I agree with that. So a point where you might see, you know, that this is being imposed on us.

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: And, Fred, could I just add just one last point on it? Is I mentioned security, and trade, and climate. Yet, together we have got to find a way—even as we have some tough stuff with China to deal with—let’s say on security—but we got to find a way to get back to what we had going into Paris, which was working together with China on climate.

STEPHEN HADLEY: Fred, that I think is the real challenge. Not to basically downplay all the other issues we have with China in the name of the cooperation for the dealing with the climate issue. We’ve got to figure out and we’ve got to be very tough-minded about this, to say: Cooperation on China is not a favor China is doing for us. It’s something China needs done, and that its population is demanding. And therefore we can, at the same time, cooperate with China on climate change but still address these other aspects of Chinese behavior that really we—our friends—United States and friends and allies—have a common interest in getting addressed.

FREDERICK KEMPE: OK. Thank you for that.

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: Can I answer that? Say, on the China—China is undoubtably a very big issue for Europe as well. I mean, what’s been happening now this year is quite remarkable in the sense that China is now a bigger trading partner for Europe than the United States. And the fact that we have the Chinese economy growing, and trade with China growing while both the US or the North American or the Western European economies are declining, it’s a shift that is happening in the world. And I talked to some economists the other day that pointed out that the Chinese consumer market is going to be—is going to be what drives the global economy in the next few years. That’s sort of the reality.

On the agreement that was mentioned, the EU-China investment agreement, that had been negotiated with seven years without much of a progress. Some of it is sort of catching up with what the US already had. But in the beginning of last year it was made clear that it’s make it or break it, we said to the Chinese. If we don’t finish it this year, skip it. So it was essentially an ultimatum from the beginning of this year that either you do something that is decent, or we skip the entire thing. And the Chinese folded, which was good from our point of view. And to some extent just catching up with what the US got, but some other things as well.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Carl, that’s a really interesting point.

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: Can I—

FREDERICK KEMPE: Just one second, Ana, and I’ll pass you. That’s a really interesting point because the Chinese folded after the election of Biden. So they wanted to close this deal and they really pushed it forward after the election. So that’s—it also shows that Xi Jinping is seizing an opportunity as quickly—

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: Yeah, true. Absolutely, they saw the strategic need to do this. They’re doing another thing which I think we should note. They are—they are saying—let’s see if it happens—that they would join the CPTPP. And I can see the strategic imperative—

FREDERICK KEMPE: Could you—not all of our listeners will know what that acronym stands for.

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: It’s old TPP, that for Canadian domestic consumption they had to call “progressive” in order to get it through. But it’s the TPP that sort of Trump went out of. That’s a much more ambitious trade agreement than the RCEP, which they already signed. And I have my doubts whether they will be able to live up to the commitments in the TPP. But if they do, that is a game changer. And if they move in that direction, there’s clearly going to be pressure on the Europeans to do the same. By the way, the Brits are intending to do it. And tremendous pressure on the US

FREDERICK KEMPE: Ana, you wanted to jump in?

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: Yeah. Well, we don’t have time, but I think that the angle that Carl presented on the bilateral agreement is—stands, but there are other aspects. And frankly, we cannot forget that this was done the last day of the German presidency, and there are other aspects.

But for me, what is important here is the ambivalence, the many Europeans sitting on the fence. And Carl, again, very diplomatically has said it’s nervousness. No, it’s mistrust. This is what at least our surveys say, that 60 percent of the Europeans think that the American system is broken. And therefore, they sit on the fence thinking that because of our need to find a future, we can find some kind of arrangement with China—forgetting, because what has not been said—and I hope that the Biden administration will be extremely tough—is that we have—the language of the agreement is that China will make its best efforts to ratify the—for instance, the forced work labor—treaties of the International Labor Organization. I mean, honestly, we cannot stand and say that we stand by liberal democracy and by human rights and accept this language in a treaty. We all have been obliged to negotiate, and negotiation is tough, and especially with China today because of the aggressiveness of their foreign policy, but there are things that you cannot sign as a European—for instance, this language.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So—

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: And the problem is that there is public opinion in all our member states that just thinks, OK, well, you know, if we have to make a living with China, let’s go for it.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So we’re the Atlantic Council. We’re down to four, maximum five minutes left here. What I think I’m hearing from the Americans is there’s a chance for bipartisan consensus on China, but across the Atlantic there is a chance that we may disagree and not be able to get our act together on China. It’s very hard to imagine a Biden administration, with the way the Democratic Party has felt about trade agreements, being forward leaning there.

The other question that’s come out is: Can pandemic recovery serve to strengthen existing relationships? So maybe for this last round just each of you, what is the transatlantic issue you think is the most promising? If you wanted to—you know, the EU reached out quickly, even before the administration came in. But what are the points one could put on the board in the first three, six months transatlantically from what you’ve heard today and what in general? And maybe just thirty seconds to a minute for each of you, and go in whatever order you jump in, and we’ll get through everybody.

LORD GEORGE ROBERTSON: Can I just say about—on behalf of the outgoing administration, one of the things that they managed to do was to break the logjam in the Middle East. And the UAE-Bahrain-Israel accord is something I think that can be built on. I think it’ll be—it’ll be an area—because the Middle East is still in turmoil with Syria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia. You know, this is still a massively dangerous area for all of us. So I think that’s an area where I think he can find some common ground and where the Europeans will be very much onside there again.

But again, it comes back to this whole question about allies and relationships and rebuilding the trust. A lot of these relationships were damaged; they were not broken. And I think, therefore, if they reach out, rebuild them, I think there are—there’s a lot of promise in a post-pandemic world where we could all work together to make the world a bit safer than it is just now.

FREDERICK KEMPE: You see, I think the Abraham Accords is a place where you could get transatlantic agreement, even though Europe—

LORD GEORGE ROBERTSON: Yeah.

FREDERICK KEMPE: —hasn’t been as enthusiastic about them.

Ernie?

SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ: OK. All right. And then I’ll jump in on your pandemic question.

I think an area—I mean, clearly, there are many things about COVID, and I agree with the earlier comment about, you know, addressing developing countries, et cetera. However, my focus instead will be transatlantic—others, as well—but transatlantic leadership in addressing the issue of avoiding future pandemics.

The reality is we all talk about this COVID as being the pandemic of the century. I have no understanding why one would reach that conclusion. We have already had six pandemics—only one at COVID-scale, obviously—in this century. This is the third COVID epidemic of this century, twenty years. We got a big, big problem. And so I think that—and frankly, my—one of my organizations, the Nuclear Threat Initiative, we very work very closely with the World Economic Forum, with a very, very strong European base, of course, working with business, et cetera, trying to establish issues like international screening mechanisms for DNA synthesis. International, we need a U.N.—probably U.N.-based international normative entity for advanced biology, if you like, et cetera.

So I think this is a fantastic area where, pooling our resources, we could make a big difference in terms of truly making COVID a once-in-a-century pandemic and not—and not the every-five-years pandemic that I fear is possible.

FREDERICK KEMPE: That’s terrific. And then let’s—

STEPHEN HADLEY: Fred, let me just—let me just add to that, quickly.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Steve, follow, and then Ana. Steve.

STEPHEN HADLEY: I agree. I think cooperation on pandemics between the United States and Europe is terrific, and I think if we can come to some consensus there we can actually provide leadership more globally and may even eventually get China to play in such a regime.

I think, in addition, this new administration I hope will join the COVAX effort, which is an effort to get vaccines to the developing world. I think if the United States and Europe were to come together and really put resources and support behind that effort, it would be a terrific message not only of US-European cooperation, but a terrific message by the new administration to the developing world that we understand and we care about what happens to them in managing this terrible disease.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Public health as a way of coming together.

Carl, and then Ana to close us.

PRIME MINISTER CARL BILDT: COVAX, obviously. Reform and augmentation of the World Health Organization. And hopefully, it’s sort of the Atlantic world can take the lead, but we need the Africans, we need the Indians, we need the Chinese. I mean, otherwise it’s not going to work. So that’s important.

Diplomacy and everything working up to COP26. There are a couple of difficult issues. The carbon border-adjustment mechanism, it sounds awful and highly technocratic, but it could be sort of explosive if we don’t handle that right in the Atlantic world.

And then there are a set of digital issues that require urgent attention. The privacy shield arrangement for free data flows across the Atlantic has been put aside by the European Court. We need to have a new arrangement. There are a couple of things on digital taxes that are boiling. That needs to be handled fairly fast. And overall, on the digital issues long term, it is—if we don’t get our act together across the Atlantic, the Chinese will have us for lunch in thirty years.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you for that, Carl. And we don’t want to be lunch.

Ana.

MINISTER ANA PALACIO: Well, you know, I mean, I fully agree. I could have said any of the above, plus climate change. We are—we are waiting for United States on climate change. We Europeans, we care about this. And I think that in innovation, for instance, United States has a lot to bring to the table, from carbon capture and usage to nuclear modular to—on this.

But I will take my cue, you know, multilateralism. I mean, it’s—I know that there is a lot of words around this, but we need a different attitude that is shown in the WTO, in practical issues, and we really expect that this administration will make a U-turn on multilateralism.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So thank you for that closing. Secretary Madeleine Albright likes to say that Americans don’t like multilateralism because it has too many syllables and it ends with -ism, so. (Laughter.) So I love it.

This was a great closing round of just a remarkable group of people. What a—what an incredible panel. I hope we can reassemble you at various times over the year. I like the way we ended because it’s really now what can we grab that’s positive.

This is an opportunity. We think there is a chance for a transformative presidency here, but it’s not a transformative presidency if you don’t have a transformed transatlantic relationship, our view. And so it’s interesting, Abraham Accords is a good positive. Iran, we have to deal with it—have to deal with it, but the Abraham Accords is something that’s happening positively. I like that.

We’ve been arguing on behalf of a pandemic prevention board. And starting across the Atlantic would be a great thing, also including the private sector.

The digital issues, Carl, that you brought to bear also, as I joked, we don’t want to be lunch, but the fact of the matter is we would have the biggest digital—free digital space if we could—in the world if we could get our act together. So these are all just terrific ideas.

On behalf of this audience, which spans time zones across the world, the Atlantic Council Global Energy Forum, thanks to all of you for participating. Thanks, as well, for the roles that you’re playing on the Atlantic Council Board and International Advisory Board.

Watch the full event

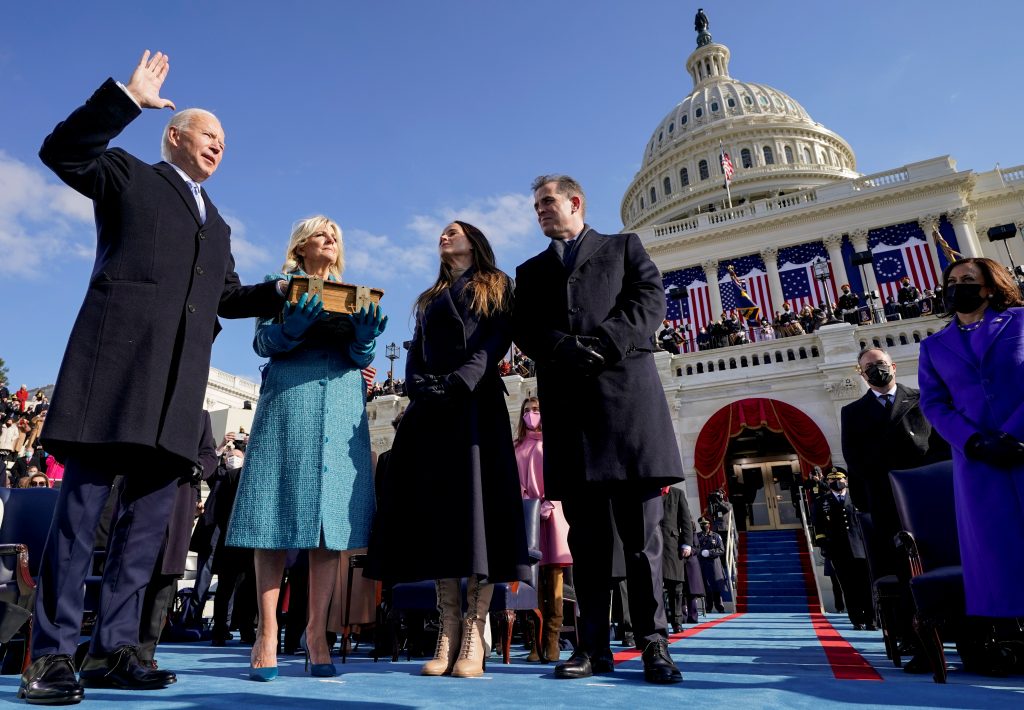

Image: Joe Biden is sworn in as the 46th president of the United States by Chief Justice John Roberts as Jill Biden holds the Bible during the 59th Presidential Inauguration at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, U.S., January 20, 2021. Andrew Harnik/Pool via REUTERS